Spidey Senses Tingling! Arachnids Feel Sex

Spider sex just got a little more interesting. Researchers now find that the spider equivalent of the penis isn't numb like once believed; it's filled with nerves that might help the spider ensure fertilization.

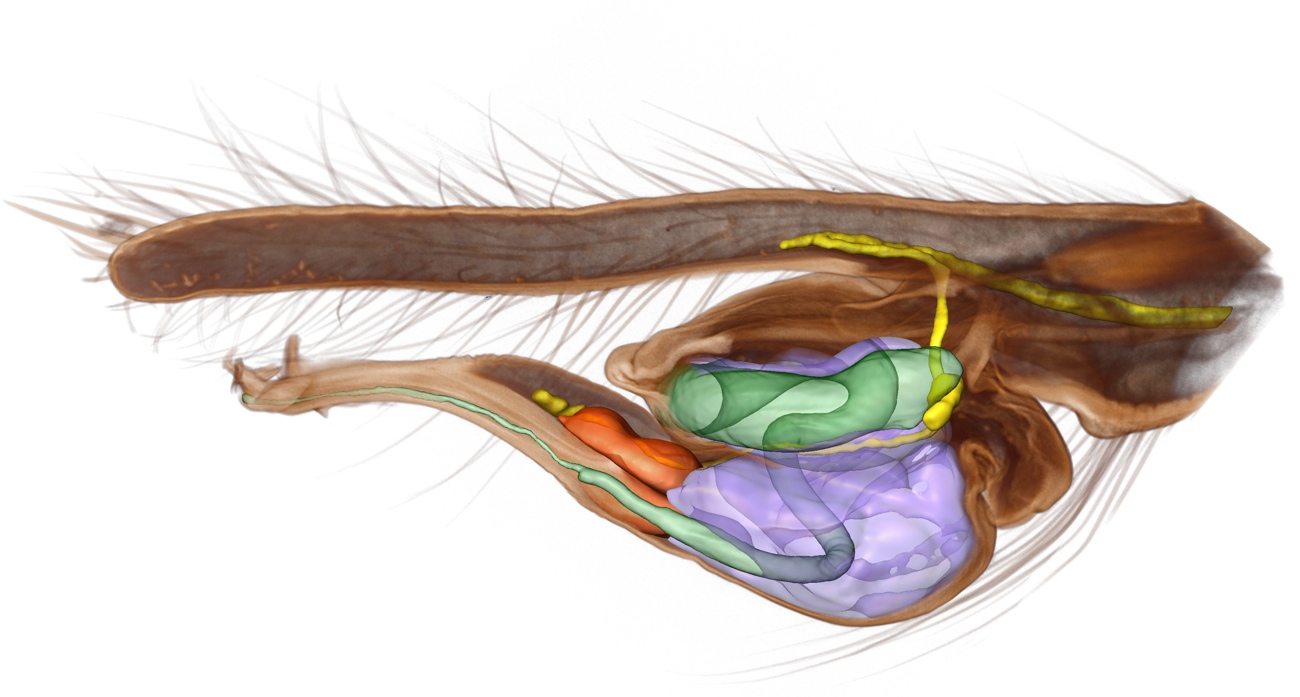

Male spiders mate using specialized appendages called pedipalps, which end in structures called palpal organs. The male uses the palpal organ to transfer sperm into the female. Several studies of the palpal organ had found no evidence of nerve tissue, suggesting the spider mating apparatus was totally numb.

Now, though, researchers have teased out the presence of nerves in this organ. It's a finding with implications beyond spider sexual satisfaction; males may be able to use sensory feedback to gauge the fitness of their female partners, adjusting the quality of their sperm transfer accordingly, said study researchers Elisabeth Lipke and Peter Michalik of the University of Greifswald in Germany. [The 7 Weirdest Animal Penises]

"Put it simply, males of this spider species are likely able to outsmart females," Lipke and Michalik wrote in an email to Live Science.

The mating game

Spider sex is not an entirely straightforward endeavor. After the male transfers his sperm, females can "choose," in ways not entirely understood, whether or not their eggs are fertilized. A female may mate with multiple males, setting off an internal competition to determine which male's sperm will fertilize her eggs. The females may also quietly dispose of sperm from males whose offspring they don't want.

The new discovery of nerves in the palpal organ suggests that males might have ways of promoting themselves in this competition. Researchers found a long nerve projecting all the way to the end of the embolus, the needlelike tip of the palpal organ. They also found two clusters of nerves, or neurons, in the body of the palpal organ.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The neurons inside the furthermost part of the male copulatory organ might allow for sensing stress and strain, and consequently might be involved in male mechanisms to stimulate the female during copulation," Lipke and Michalik said.

Sensing sex

The researchers also found an innervated gland in the palpal organ. Spiders might use this gland to adjust their sperm output, perhaps investing less in females unlikely to keep their sperm.

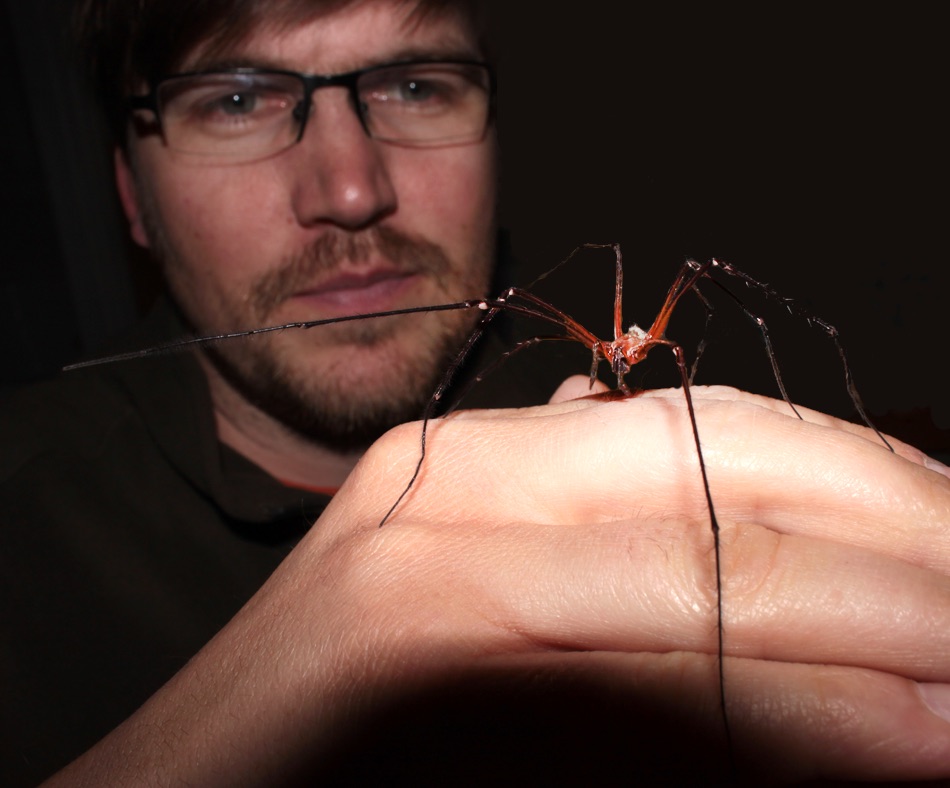

The researchers conducted their study in the Tasmanian cave spider (Hickmania troglodytes), a spindly beast with a leg span of up to 7 inches (18 centimeters). But the researchers said they suspect other spiders have genitals that provide the full sensory experience, too.

"Our study has just provided the foundation to further focus and (re)-investigate the copulatory organ of other spider species in detail," the researchers said.

The findings are detailed today (July 7) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.