Destroyed Iraqi Holy Sites Find New Life Online

TORONTO — Researchers are embarking on an ambitious project to bring part of Iraq's destroyed heritage back to life.

Over the past few years the world has watched as the Islamic State has destroyed historical monuments and committed acts of genocide in Iraq and Syria. While the group labels itself "Islamic," they've been destroying both Islamic and Christian holy sites along with sites that predate the founding of both religions, said archaeologist Clemens Reichel, a curator at Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum, in a presentation he gave last spring.

However, thanks to the Iraq travels of Amir Harrak, a professor at the University of Toronto, researchers have a chance to bring a bit of this destroyed heritage back online. Harrak is a native of Mosul (he left in 1977), a city that has been under the Islamic State'scontrol for more than a year.

Between 1997 and 2014, Harrak made several trips to cultural heritage sites throughout Iraq, cleaning and recording engraved inscriptions that date between the seventh and 20th centuries. During a trip to Mosul in 2014, he recorded inscriptions and art at the monastery of Mar Behnam. Islamic State fighters captured the city and monastery in June 2014, but Harrak managed to leave before they arrived. Since then, the militant grouphas destroyed the monastery along with many sites in Mosul and other parts of Iraq. [See Photos of Iraq Heritage Sites Taken by Harrak]

Because of this destruction, the photographs he took during these trips (about 700 in total) have become scientifically irreplaceable. He's now working with the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents (CCED) to create an online database of all the inscriptions, which will allow new research on them and, despite the destruction, allow more people to see them than ever before.

"Much if not most of our [photographic] collection may be the only extant copies of now-damaged or lost inscriptions," said CCED director Colin Clarke. "While ISIL is knocking this down, we're here in Canada putting it back up and to even a wider audience than it's ever seen."

Iraq travels

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Harrak told Live Science that, in the years before the 2003 American invasion, the country was suffering from economic embargoes; but the security situation was stable and he could move freely. "I traveled north, south, east and west without any hindrance," when carrying documentation from the university and permission from Iraqi officials, he said.

He worked to photographas many inscriptions as he could. Some of the inscriptions were already in poor shape and he had to clean them carefully before photographing them. "There [is] dust in my body from those inscriptions to make them really clear [so that] I could photograph," Harrak said.

The inscriptions were written in a variety of languages. Many of them were in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic that was commonly used by Christians in Iraq from ancient to modern times. (Harrak is an expert in this dialect.) There are also many inscriptions in Garshuni, a script that records the Arabic language in Syriac letters. [Photos: New Archaeological Discoveries in Northern Iraq]

"The Harrak Collection (of photographs) is the largest corpus of Iraqi-Syriac and Garshuni inscriptions in the world," Clarke said.

New Discoveries

By applying a computer analysis to the photographs scientists could potentially make new discoveries. Also, the fact that they will be freely available online to everyone means that every researcher in the world can access the images.

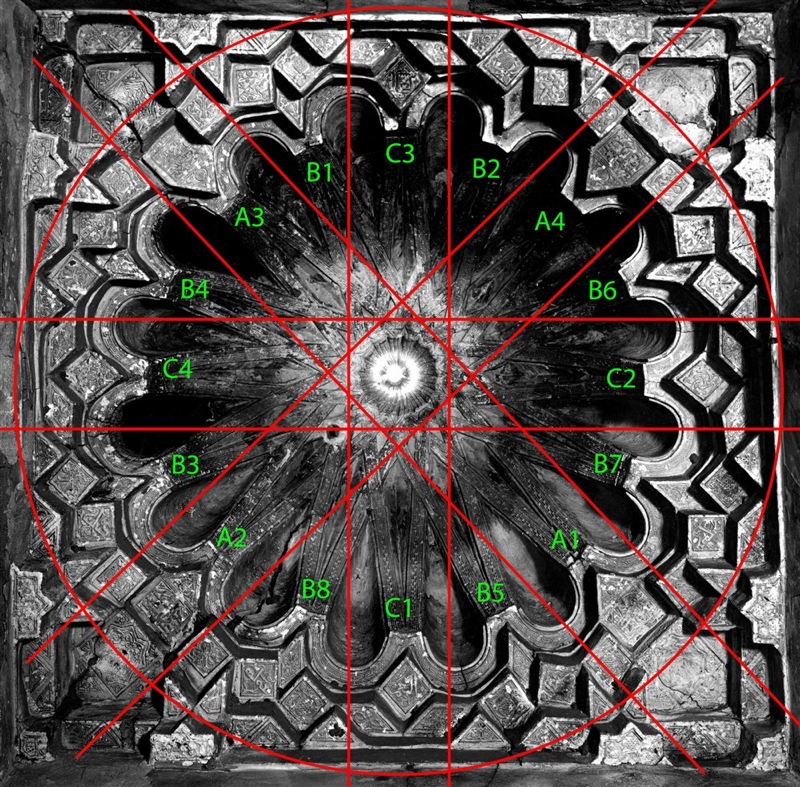

For instance, one image reveals a ceiling vault (called the Virgin's Vault) covered with a confusing array of inscriptions that are written in Syriac and Arabic.

Even if you can read the languages they don't appear to make sense, the archaeologists said. "You go left to right or right to left, it makes no sense," Clarke said. The key to understanding the inscriptions is to know which group of inscriptions is read after the other, the researcher said.

When you know which group of inscriptions connects to another, a pattern in the shape of a star begins to emerge.

"You have to know how to read it and when you do it creates a picture of the mind, a geometrical design that is a cross superimposing a cross… to read it fluently it creates a star pattern," Clarke said. This star pattern was popular among the Assyrian Christian community, said Harrak, and may go back to ancient times.

Citizen science

You don't need a doctoral degree to play an important role in this project.

Given that many of the inscriptions recorded by Harrak are now destroyed or damaged, CCED has an enormous responsibility. "If you enter the Baghdad Museum they wouldn't have copies of what's been lost that we have here," Clarke said.

CCED is an all-volunteer team, and they urgently need volunteers with technical expertise who can help them complete the database (only one-third of which is online) and make it more user-friendly, Clarke said.

They are also hoping to receive donations to fund their work. "Absolutely everything has been done on zero funding," Clarke said, with people paying expenses out of their own pocket. He asks anyone who can help to contact CCED.

Saving heritage

As awareness of the team's work grows, people whose families have fled Iraq are taking notice. [Top 10 Battles for the Control of Iraq]

Toronto, where the project is based, is home to a large number of people from the Assyrian community, a mainly Christian group based in Iraq, which has been targeted by the Islamic State and other militant groups.

Clarke has been talking with members of this community, hearing stories of villages being overrun and family members being held hostage by the Islamic State. "I recently met a man whose 81-year-old father has been taken hostage along with four other family members back in Iraq," Clarke said.

He's received photographs of destroyed sites from members of the community who have asked him to put them in the database so that their heritage can be preserved.

"A young Iraqi man sent me photographs of his grandfather's tomb in Tel Kef," Clarke said, adding that the young man knew the tomb and the church where it resided had been destroyed by the Islamic State group. The tomb had a long inscription engraved on it, which had also been destroyed.

The young man asked Clarke: "Could you please [put] this up on your site, that way it's not lost forever." The inscription is now online.

Follow us@livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.