Why Atticus Finch's Racist Shift in 'Watchman' Could Be an Anomaly

The character Atticus Finch, long revered by many as a paragon of justice, has transformed into an unapologetic racist in Harper Lee's new novel, "Go Set a Watchman" (Harper, 2015). But it's curious that Atticus endorses racism in his old age, as most people tend to become more tolerant in their later years, studies find.

Atticus' reversal of attitude, discovered by his grown-up daughter, Scout, during an annual visit home, shows that Atticus, always somewhat of an eccentric, is still an anomaly.

"To be a progressive who champions civil rights and do a 180 makes one very much an outlier," said Charles Gallagher, a professor of sociology at La Salle University in Philadelphia. [7 Ways the Mind and Body Change with Age]

Aging Atticus

Atticus may be fictional, but readers admire the character for defending Tom Robinson, a black man in the novel unjustly accused of raping a white woman in Alabama during the 1930s. In Harper Lee's "To Kill a Mockingbird" (J.B. Lippincott Company, 1960), Atticus deftly defends Robinson, but loses the case when the Jim-Crow-era jury finds his client guilty.

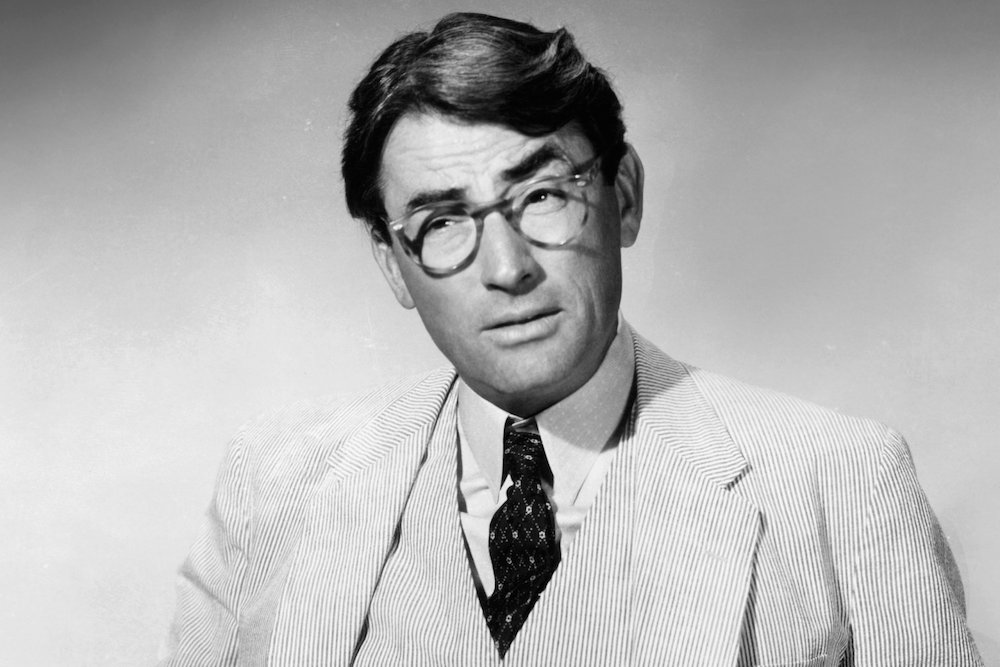

Many "Mockingbird" readers respect Atticus for standing up against racism, even though he ultimately lost the case. Lee won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961 for writing the book, while the 1962 film adapted from the novel won several Academy Awards, including best actor for Gregory Peck, who played Atticus.

"Watchman," released July 14, shows that an elderly Atticus is remarkably different. He tells his daughter that "Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people," after she catches him attending a meeting organized by the citizen's council, a white supremacist group.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scout is furious and hurt when she learns about her father's views, just as many "Mockingbird" readers undoubtedly will be.

"I believed in you. I looked up to you, Atticus, like I never looked up to anybody in my life and never will again," Scout says in "Watchman." "If you had only given me some hint, if you had only broken your word with me a couple of times, if you had been bad-tempered or impatient with me — if you had been a lesser man, maybe I could have taken what I saw you doing."

Racial attitudes

Atticus' old age may partly explain his changed perceptions, studies have shown. People ages 18 to 39, as well as 60 years or older, tend to change their attitudes more than middle-age people do, according to a study of 25 surveys on sociopolitical attitudes taken between 1972 and 2004.

At the ripe-old age of 72, Atticus is in prime territory for changing his mind, said Matthew Hughey, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut, who was not involved in the study.

However, the research, published in 2007 in the journal American Sociological Review, also found that when people change their attitudes, it's usually "toward increased tolerance rather than increased conservatism," the researchers wrote in the study.

People typically change their attitudes to match changing societal values, evidence shows. For example, in 1942, 68 percent of white people said that black and white children should attend separate schools, according to a 2008 report on racial attitudes in the United States. In 1995, just 4 percent of whites surveyed said they believed in segregated schools, the report said. [7 Reasons America Still Needs Civil Rights Movements]

That change happened, in part, because subsequent generations are reportedly more accepting of integration, and outnumber the aging old-timers, Gallagher said.

People's attitudes are generally stable over time, he said, but often mirror society if they do change.

"The idea is that you have a major event," such as the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which outlawed segregated schools, Gallagher said. "Slowly, that becomes not just the law of the land but also a cultural norm."

The same liberalizing of cultural and individual views has happened with laws supporting women's rights, interracial marriage and gay rights, he said. But not everyone follows that path.

"Atticus is atypical in the sense of what happens with racial attitudes over time," Gallagher told Live Science. "That certainly doesn't mean that Atticus Finches don't exist. I know people who, as they get older, they get more conservative."

Atticus dethroned

However, maybe Atticus wasn't ever a blazing liberal. "Mockingbird" has some troubling racial undertones, experts say.

"The whole narrative structure is one in which white characters are the ones who are doing the acting," Hughey said. "[In the book,] blacks exist to be acted upon rather than be active agents."

In reality, black people played an enormous role during the Civil Rights era, from organizing bus boycotts to getting cases to the Supreme Court, he said.

Still, most people view "Mockingbird" as a progressive book for the 1960s, Hughey said. It showed the entrenched state of white supremacy, but Hughey and many other people say Atticus is an overly paternalistic (and unnecessary) white savior who defends Robinson, but doesn't actually fight the larger social order. Such critics include essayist Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote a controversial 2009 piece about Atticus in the New Yorker.

"I think Atticus, in some ways, always demonstrated racial attitudes," Hughey said. "Blackness becomes this thing to be saved and only can have salvation by submitting to white do-gooders."

Conversation starter

Yet, many people remember Atticus as the hero of "Mockingbird," Gallagher said.

Atticus in "To Kill a Mockingbird" is how America wants to see itself, Gallagher said. "He's the person who would stand up to a pitchfork crowd and stand up for someone who is defenseless," Gallagher added.

Now, readers can ask themselves if they and the society they live in are more like the Atticus in "Mockingbird" or the one in "Watchman," he said.

"America believes that we are Atticus Finch one," Gallagher said. But "Atticus two forces us to talk about it."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.