Charred Remains of 1,500-Year-Old Hebrew Scroll Deciphered

A burned 1,500-year-old Hebrew scroll found on the shore of the Dead Sea was recently deciphered, 45 years after archaeologists discovered it, researchers in Israel have announced.

"The deciphering of the scroll, which was a puzzle for us for 45 years, is very exciting," Sefi Porath, the archaeologist who discovered the scroll in 1970 in Ein Gedi, Israel, said in a statement from The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The Ein Gedi parchment scroll is the oldest scroll discovered from the Hebrew Bible since the Dead Sea Scrolls, which date to the end of the Second Temple period, about 2,000 years ago.

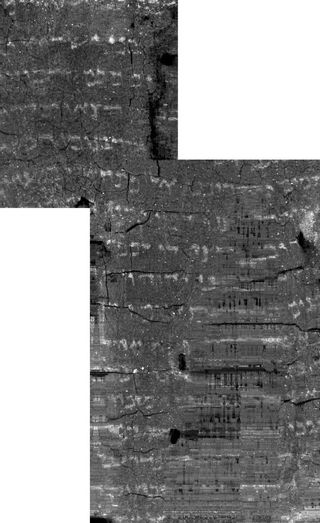

The parchment scroll was so charred that it was illegible to the naked eye. Only with advanced technology did the scroll reveal the opening verses of the book of Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible. [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

Scorched scrolls

The researchers weren't expecting to be able to pull information from the burned scroll.

"This discovery absolutely astonished us; we were certain it was just a shot in the dark but decided to try and scan the burnt scroll anyway," said Pnina Shor, curator and director of the IAA's Dead Sea Scrolls Project.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fire damage to the Ein Gedi scrolls made themimpossible to open, so the IAA worked with scientists from Israel and abroad to scan the scrolls with a microcomputed tomography machine (micro-CT), which is "just like what they do in the doctor's office but at a very high resolution, probably a hundred times more accurate than the medical procedures that we do," said Brent Seales, a professor of computer science at the University of Kentucky. Seales analyzed the scans with a digital imaging software that virtually unrolled the scroll and allowed him to visualize the text.

Seales wanted to unpack the layers of the scroll to reconstruct how the text would look if the scroll were opened. "Initially, we didn't know if there would be writing, or what the writing would be, so it was absolutely a big mystery revealed right at the lab," Seales told Live Science.

'Garden of Eden'

The scrolls were unearthed in Ein Gedi, which translates to "Spring of the Goat," a desert oasis on the western shore of the Dead Sea, about 20 miles (32 kilometers) southeast of Jerusalem. Based on ruins of a Chalcolithic, or early Bronze Age, sanctuary dating to the year 4000 B.C., Ein Gedi's first known residents established themselves there about 5,000 years ago.

The oasis is notable in the Bible as the site where King David fled to escape the jealous and vengeful King Saul. David survived and eventually succeeded Saul as King of Israel from around 1010 to 970 B.C.

"Ein Gedi was a Jewish village in the Byzantine period (A.D. 4th to 7th centuries) and had a synagogue with an exquisite mosaic floor and a Holy Ark," Porath said. This marked the first time that an archaeological dig had uncovered a Torah scroll in a synagogue, Porath noted. [Image Gallery: Ancient Texts Go Online]

The Holy Ark is a chest or cupboard, often ornately carved, with doors that open away from each other to reveal the Torah scrolls. These arks typically sit toward the front of a synagogue.

Ein Gedi "was completely burnt to the ground, and none of its inhabitants ever returned to reside there again, or to pick through the ruins in order to salvage valuable property," Porath said. During archaeological excavations of the burned synagogue, researchers found fragments of the burned scrolls; a bronze, seven-branched candelabrum (or menorah); the community's money box holding 3,500 coins, glass and ceramic oil lamps; and perfume vessels, Porath explained.

"We have no information regarding the cause of the fire, but speculation about the destruction ranges from bedouin raiders from the region east of the Dead Sea to conflicts with the Byzantine government," Porath said.

Although the Ein Gedi scrolls were recovered not too far from the well-known Dead Sea Scrolls, they are considered separate Seales said, because they were found in a synagogue.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were hidden from approaching Roman armies in caves near Qumran in the Judean Desert, which extends east of Jerusalem to the Dead Sea. The ancient scrolls weren't discovered again until 1947, when a bedouin shepherd of Arab ancestry happened upon them.

The iconic Dead Sea Scrolls date from the third to first centuries A.D. Although Hebrew is most frequently used throughout the scrolls, about 15 percent is in Aramaic, and several writings are in Greek. The 230 manuscripts are often referred to as "biblical scrolls" because they are copies of works that make up the Hebrew Bible.

The text

On the newly decipheredscroll, the text (from the beginning of the book of Leviticus), translated from the original Hebrew, reads as follows:

“The Lord summoned Moses and spoke to him from the tent of meeting, saying: Speak to the people of Israel and say to them: When any of you bring an offering of livestock to the Lord, you shall bring your offering from the herd or from the flock. If the offering is a burnt offering from the herd, you shall offer a male without blemish; you shall bring it to the entrance of the tent of meeting, for acceptance in your behalf before the Lord. You shall lay your hand on the head of the burnt offering, and it shall be acceptable in your behalf as atonement for you. The bull shall be slaughtered before the Lord; and Aaron’s sons the priests shall offer the blood, dashing the blood against all sides of the altar that is at the entrance of the tent of meeting. The burnt offering shall be flayed and cut up into its parts. The sons of the priest Aaron shall put fire on the altar and arrange wood on the fire. Aaron’s sons the priests shall arrange the parts, with the head and the suet, on the wood that is on the fire on the altar." (Leviticus 1:1-8).

The biblical text marks the first time a Torah scroll was found inside a synagogue in any archaeological excavation, according to the IAA.

"The knowledge that we are preserving the most important find of the 20th century and one of the Western world's most important cultural treasures causes us to proceed with the utmost care and caution, and use the most advanced technologies available today," Porath said.

"This collection at the IAA is full of other fragments that might be analyzed, so in a way, this is a beginning rather than an ending," Seales said.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science