Dire Climate Warning by NASA Scientist Raises Questions

NASA’s former climate chief has issued a stark new study that finds that the world’s current climate goal could be inadequate and may not prevent catastrophic losses from rising seas, ocean temperatures and changes in global weather. But the extreme nature of his projections has some scientists questioning the methods he used and the results he reached.

Global leaders and scientists have agreed that keeping global warming to within 2°C of pre-industrial temperatures represents a safe level of climate change. The new findings, published as a discussion paper in the European Geophysical Union’s Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics journal, indicate something else. They show that 2°C of warming could lead to runaway ice melt at the poles, causing sea level rise and ocean circulation changes by 2100 that are much more extreme than most current projections.

The new study says that limiting warming to 2°C “does not provide safety, as such warming would likely yield sea level rise of several meters along with numerous other severely disruptive consequences for human society and ecosystems.”

The research was lead by James Hansen, the former head of NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and current Columbia University faculty. Hansen rose to prominence for his research and Congressional testimony in 1988 about the role of carbon dioxide and other human greenhouse gas emissions in causing the global temperature to rise. He has advocated for keeping atmospheric carbon dioxide around 350 parts per million (ppm) to avoid dangerous climate change. They recently passed the 400 ppm milestone globally.

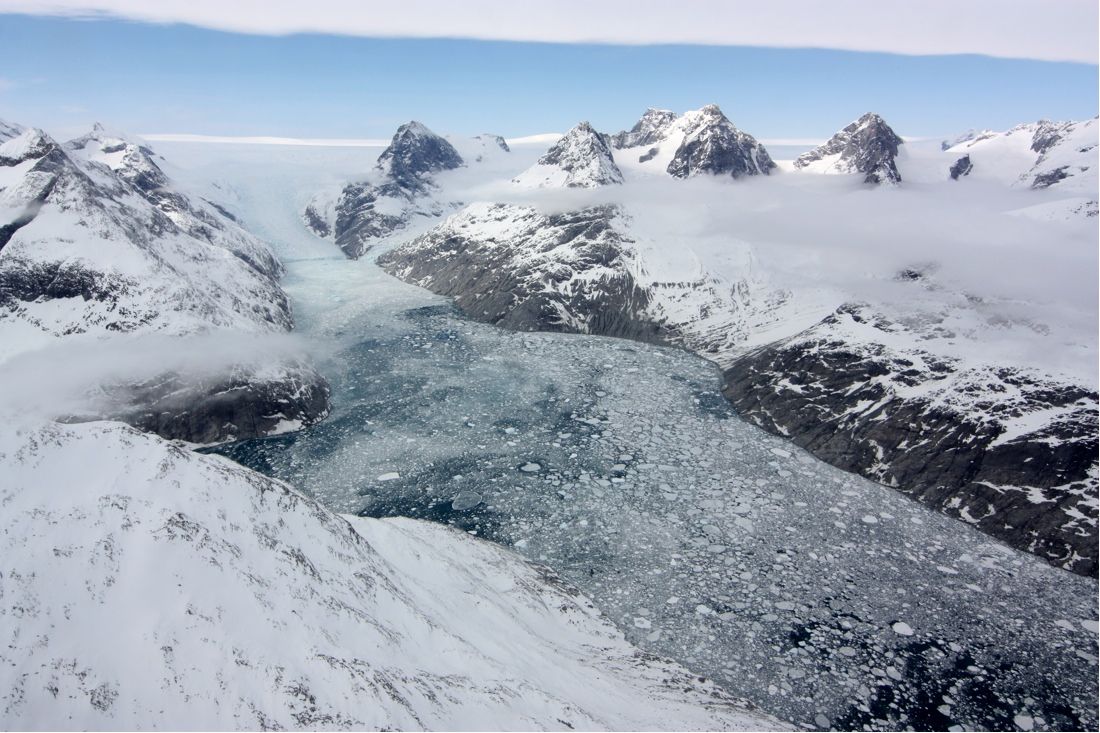

The paper uses paleoclimate data and modeling to show that if ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica continue to double their melt rates every 10 years as they currently are, sea levels could rise up to 16 feet as soon as 2100.

A sudden influx of fresh, cold water to oceans around Antarctica and Greenland could have other notable impacts. The study argues that it could slow down ocean conveyor belts that shuttle water around the world’s oceans and alter air temperatures and storm tracks. Most provocatively, the study indicates it could cause cooling over the southern third of the globe as well as parts of the northern Atlantic and Europe and slow warming in other parts of the globe.

The changes the study outlines are dramatic and much more alarming than the upper limits most scientists have outlined as possible if human greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current trends. The upper level of sea level rise projections from the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report indicates a rise of 4 feet by 2100 is possible. There is some evidence the West Antarctic Ice Sheet — which contains enough ice to raise seas by 13 feet — has entered collapse, but it’s unlikely to completely melt away by century’s end.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“I agree with the overall magnitude of sea level rise that they are interpreting for the last interglacial,” Andrea Dutton, a geochemist at the University of Florida, said. “What does not come across in this paper is that there is still debate regarding the timing of ice-sheet collapse during this warm period.”

Dutton led research published last week in Science showing that sea levels rose by 20-30 feet about 125,000 years ago, the same period analyzed in the new Hansen study. She is working with a group of scientists to get a better handle on how fast ice melted then as well as during other periods of rapid sea level rise in the past 3 million years.

“Setting the rates can be a challenge, but we’re starting to develop tools and techniques to understand them,” she said.

Likewise, there is some indication that ocean circulation is already slowing in the North Atlantic due to Greenland’s current melt. But the new findings might overstate its impact on air temperatures and the chances of ever-increasing melt rates in Greenland, according to Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State who authored a paper on the topic early this year.

“Their scenario assumes exponentially increasing meltwater over time, which may not be realistic,” he said. “Moreover, it is based on the use of a low-resolution ocean model which does not resolve key real-world ocean currents like the Gulf Stream. In the real world, such current systems play a key role in transporting heat to higher latitudes, and make it much more difficult to cool off the extratropics simply by a slowdown/collapse of the ‘conveyor belt.’ ”

The journal the findings are published in is an “interactive journal,” meaning that an editor has approved the paper but it will go through peer review in the public eye. Hansen said the reason for publishing this way rather than wending through the peer review process was to make the findings available to the public and policymakers ahead of the Paris climate talks this December.

“The situation is more urgent than many politicians seem to realize and we’ve made the scientific story clearer,” Hansen said.

What may end up becoming clearer is the peer review process, however. The discussion of the paper will unfold in front of the public and could result in major revisions to the paper before it is officially accepted for publication. This could well be a standard for the future of science publishing, though Mann questioned the idea of shining such a bright light on the results before they have been through the peer review process.

In its current form, the paper stands as an outlier for the scope and severity of the changes global warming could bring, making it an unlikely candidate to influence policy discussions. Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said the paper is ill-suited for that kind of use, anyway.

“The new Hansen et al. study is provocative and intriguing but rife with speculation and ‘what if’ scenarios,” he said. “It has many conjectures and huge extrapolations based on quite flimsy evidence but evidence nonetheless. In that regard it raises good questions and topics worthy of further exploration, but it is not a document that can be used for setting policy for anthropogenic climate change, although it pretends to be so.”

You May Also Like: NASA Shows Off Spectacular New Blue Marble Record Hot First Half May Herald Warmest Year Yet Arctic Sea Ice Volume Rebounds, But Not Recovering Marine Conservationists Work to Curb Ocean Stress

This story was originally published on ClimateCentral.