Beautiful Butterfly on Brink of Revival, Despite Century of Threats

Michael Sainato is a freelancer with credits including the Miami Herald, The Huffington Post and The Hill. Follow him on Twitter at @msainat1. Sainato contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Formed nearly 12,000 years ago by a receding glacial lake, the Albany Pine Bush Preserve in New York hosts a rare ecosystem, one of only 20 inland pine barrens in the world. Its sand dunes hold a unique variety of habitats, yet nutrient-poor soils, that support a diverse range of plants and animals that thrive in an environment too barren to support competing species.

This unusual landscape, surrounded by development, also holds within it an equally rare species: the endangered Karner blue butterfly, named by lepidopterist (and "Lolita" author) Vladimir Nabokov in 1944. And yet this U.S. National Natural Landmark seems always on the brink of destruction. In the face of large-scale development in the area, grassroots organizations like Save the Pine Bush have had to repeatedly rescue the park — and the blue lupine flowers that feed the local community of Karner butterflies — from annihilation. As with many endangered U.S. landscapes, threats from encroachment have been steady, dating back two centuries. [Butterfly Facts]

First came the railroads

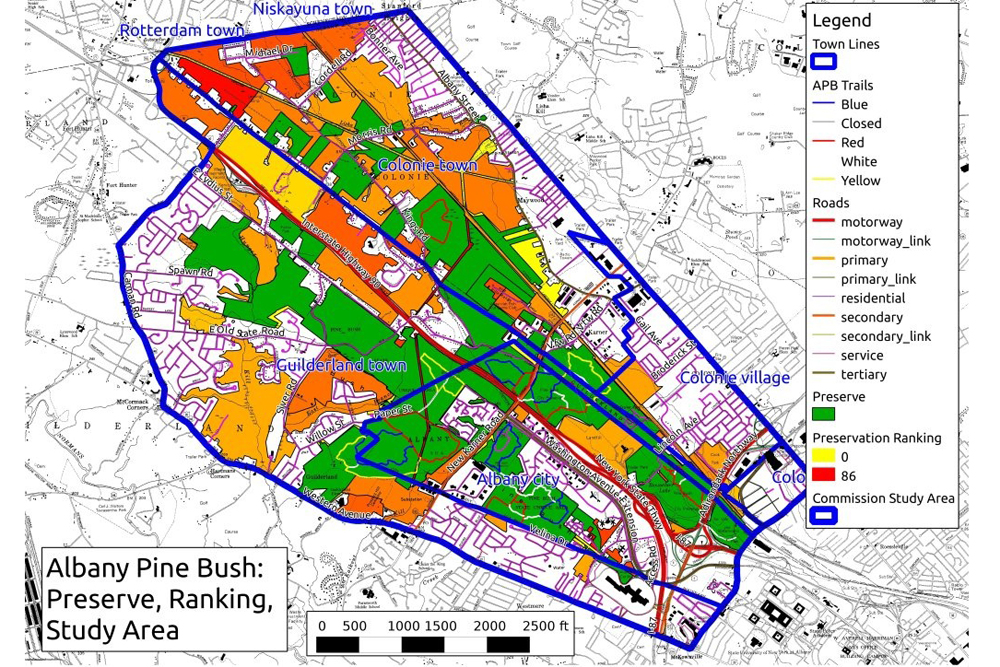

The 3,200-acre Albany Pine Bush Preserve — what's left of more than 25,000 acres of pine barrens — is heavily fragmented, consisting of islands of protected land in a highly developed area of upstate New York.

The sandy, well-drained soils are dominated by vegetation that has ecologically adapted to dry conditions and periodic droughts, but it is a biologically diverse ecosystem that supports nearly 1,300 species of plants; 156 species of birds; more than 30 species of mammals; and 20 species of amphibians and reptiles. The Pine Bush has 64 wildlife "Species of Greatest Conservation Need," as listed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

The pine barren first faced major industrial development in the form of one of the nation's original passenger railroads, built in 1830. A DeWitt Clinton locomotive cut through the pine bush as an alternate route for Erie Canal travelers, bridging the distance between the cities of Albany and Schenectady.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1858, part of the pine bush was divided into plots and sold to distant buyers at high prices. Yet upon seeing the land in person, buyers deemed it useless and resold it to other distant buyers, and a perpetual cycle of real estate buying and selling in the area began.

Because of this disinterest in the land for agricultural and development purposes, much of the pine barrens remained unscathed until the 1950s.

In the post-World War II era, the area began to see rampant development with the construction of Interstate 90 and other major city roads. Then, in 1969, Albany's mayor, Erastus Corning II — who held the position for 42 years — approved a new landfill to be placed in the region, despite the presence of a large underlying aquifer that could be affected by landfill leaks.

A decade later, a proposal threatened to turn much of the pine bush into four housing development projects. On Feb. 6, 1978, the city of Albany held a public hearing on the proposal. Nearly 40 activists — mostly SUNY Albany students from the small independent environmental science program at the school — showed up, despite a threatening snowstorm. As the storm progressed, the city planner closed the hearing midway through. The project was ultimately approved, unanimously, by the City of Albany Planning Board.

The outcome, and their snowstorm dismissal, inspired the activists to form Save the Pine Bush, a grassroots organization that has challenged development proposals in the pine bush through litigation ever since. Despite their efforts — and legislation that created The Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission, a public-private partnership, in 1988 — much of the pine bush has been developed.

Only 6,200 acres of undeveloped land remain, with 3,000 still outside the current preserve boundaries and at risk of being developed.

Landfill expansion

In 1989, the city of Albany proposed an expansion of the landfill, culling the pine bush by an additional 25 acres. Save the Pine Bush filed a lawsuit to stop the development, which would encroach into Karner blue butterfly habitat, as the insect had been listed as endangered just the year before. Members paid the $30,000 needed for the lawsuit — with some cashing out their retirement savings, as the group's monthly lasagna dinner fundraisers were woefully insufficient.

The City of Albany, which hired outside counsel to handle the case, won, but agreed to designate the tipping fees from dumping in the landfill to fund the Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission.

Three hundred lupine plants were removed from the expansion site in an attempt to replant them elsewhere, but all of the plants died, as they can only survive in the presence of a bacterium. The plants have a symbiotic relationship with these bacteria, which are necessary for them to grow in nutrient-deficient soils where other species cannot thrive.

The mall

In 1980, rumors circulated in Albany that a mall would be built on 190 acres of the pine bush, and in 1984, construction began after a yearlong legal battle. (The mall was constructed by a company whose owner and founder, somewhat ironically, lives in a small town that limits retail development).

The development proposal for the mall was required by law to provide an environmental impact statement, which allowed public testimony on what that statement should entail. Save the Pine Bush's lawyer, Lewis B. Oliver Jr., had to subpoena members throughout the year so they would be able to take time off work to give testimony.

"An administrative law judge ruled in favor of our suit against development due to the air pollution the mall would create, but the ruling was overruled by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation less than 72 hours later," Jackson said. "The ecosystem, the pine bush, at this point was mostly privately owned; the state or city only owned a few parcels of land within the ecosystem. The land the mall was to be built on was, like most land in the pine bush, privately owned."

One of the mitigation measures of the development proposal was that a 2-acre site, called Butterfly Hill, would be set aside for protection. "For a while, it was one of the only places the Karner blue butterfly could be found in the area, of which just over 100 were left," Jackson said. "Any number under 1,000 puts a species in jeopardy of genetic inbreeding. A single weather event could have extirpated the entire species from the area."

The amusement park, the bank and the hotel…

In 1995, the Karner Dunes Adventure Park was supposed to be built on a 6-acre site of the Pine Bush Preserve. Save the Pine Bush lost the suit to stop development, but the town of Guilderland, which had jurisdiction, refused to allow it to be built. The owner sold the land to The Nature Conservancy, and lupine was replanted at the site to expand Karner blue butterfly habitat.

In 2001, a bank proposed to expand its headquarters, which were on a 6-acre site in the Pine Bush ecosystem, in the middle of prime habitat for the Karner blue butterfly. Save the Pine Bush failed to get an injunction for the office's construction years earlier, but the group succeeded in stopping rezoning of the land from residential to commercial, crippling the bank's plans for further expansion. The bank, unable to modify the multimillion-dollar building in which it invested, conducted a land trade in 2008 with the state of New York to move its office elsewhere.

The building now serves as the office for the Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission and a discovery center to provide visitors with interactive exhibits and outreach activities.

In 2003, Save the Pine Bush filed a lawsuit opposing the development plans for the construction of a hotel in the pine bush. The case was not settled until 2010, in favor of the hotel, but the judgment set the precedent for case law that gives environmental groups standing to file lawsuits based on environmental concerns. [Photos: Butterflies Drink Turtle Tears]

The Karner blue butterfly recovers

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Karner blue butterfly has suffered nearly a 99 percent reduction in its population across its historic range over the last century, mostly due to habitat destruction. Its numbers in the Albany Pine Bush preserve have recovered from fewer than 200 in the 1980s to estimates in the thousands, currently. The state of New York began purchasing parcels of land to dedicate to the preserve, which now covers up to 3,200 acres, and there are plans to expand the preservation area.

"Over the past decade, active habitat management and an accelerated Karner blue butterfly recolonization program in the Albany Pine Bush has helped the species recover to the point at which it has reached its recovery threshold in the area, and captive rearing may not be necessary in the future, although the butterflies will continue to be monitored and protected within the preserve," said Christopher Hawver, executive director of the Albany Pine Bush Commission.

Hawver has been working with the preserve since 1993 when he started volunteering on a prescribed burn to maintain habitats in the preserve, which depend on periodic fire. After several promotions, he worked his way up to his current role, which he has held since 2000.

"People should visit the Albany Pine Bush Preserve not only because its 3,200 acres [make up] the largest open recreation area in the Albany metro capital region, but also because it is one of [the] most globally rare ecosystems on Earth," Hawver said.

During the past 15 years, through intensive habitat promotion by the preserve's commission and its partners, invasive species removals, native species plantings and recovery strategy implementations, the preserve and the biodiversity that thrives in it are amid a strong recovery from the effects of habitat fragmentation. The efforts of have saved and revitalized a threatened ecological treasure.

In fragmented habitats, nearly half of all species are lost within 20 years, and this downward trend continues over time. Across the United States, fragile and rare ecosystems have suffered large scale destruction at the hands of voracious development, increasing populations, and the resources our lifestyles call for.

And yet, through conservation and intense recovery and land management, it is possible to give nature a helping hand to resist the negative impacts of a shrinking wilderness.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.