Drought Toll: California Now Missing 1 Year’s Worth of Rain

The amount of rain that California has missed out on since the beginning of its record-setting drought in 2012 is about the same amount it would see, on average, in a single year, a new study has concluded.

The study’s researchers pin the reason for the lack of rains, as others have, on the absence of the intense rainstorms ushered in by so-called atmospheric rivers, the ribbons of very moist air that can funnel water vapor from the tropics to California during its winter rainy season.

Overall, the study, accepted for publication in the Journal of Geophysical Research – Atmospheres, found that California experiences multi-year dry periods, like the current one, and then periods where rains can vary by 30 percent from year to year. Those wet and dry years typically cancel each other out.

Drought Takes $2.7 Billion Toll on California Agriculture Record Warmth Continues to Bake U.S. West How This El Niño Is And Isn’t Like 1997

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation, one phase of which has ushered in some of the state’s wettest years, only accounts for about 6 percent of overall precipitation variability, the researchers found.

Drought began creeping across the California landscape in 2012 and has continued to mushroom year after year as winter rains and snows were much diminished. The atmospheric rivers that normally funnel in moisture-laden air were thwarted by a persistent area of high pressure that blocked them from reaching California. This winter, precipitation that did manage to fall mostly did so as rains thanks to record-high temperatures linked to extremely warm waters off the coast, leaving the snowpack at record low levels.

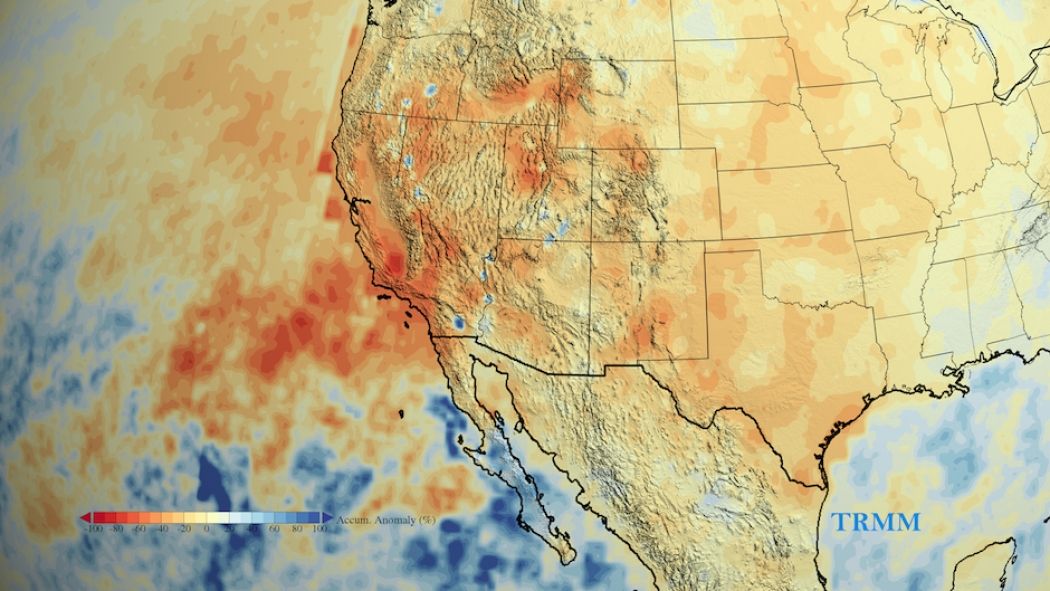

The new study looked at satellite measurements of rainfall from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission(TRMM) satellite, as well as a recreated climate record that used both observations and model data to gauge how much California’s annual precipitation varied and how much it was in the hole after four years of drought.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that in an average year, the state sees about 20 inches of rain; it turns out that’s also about the amount of missing rain since 2012.

To dig out of the drought in just one winter, the state would have to see 200 percent of its normal yearly rain, to cover both that year’s rain and make up the missing amount.

That wet a winter isn’t very likely happen, Daniel Swain, a PhD student at Stanford University, said in an email. And if it did occur, it would mean major flooding, he added. Swain wasn’t involved with the new research.

The study also looked at another recent dry period, from 1986 to 1994, and found a 27.5-inch precipitation deficit over that period. While that was overall greater than the current drought, the per year rain deficit is much higher this time around, Swain pointed out.

Added to that, “temperatures in CA during the current drought have been warmer than during any previous drought on record, which has greatly amplified the effect of the precipitation deficits,” and helped fuel the wildfires currently flaring up around the state, Swain said.

Many are hoping the current El Niño will make a serious dent in the drought, as it looks to become a strong event, and those are associated with higher odds of increased winter rains over at least parts of the state.

The study found that the whole El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle only accounts for about 6 percent of the variation in yearly California precipitation. That cycle encompasses not just strong El Niños, but weak ones, as well as neutral and La Niña conditions, and when separated out “very strong events (like the El Niño currently underway) exert a far greater influence upon California climate than weak ones,” Swain said. So this year’s El Niño could play a major role in what precipitation California sees.

What’s important this year, Swain said, is where the precipitation falls and how much of it falls as snow to build back up the snowpack that keeps water flowing into reservoirs come the warm, dry days of summer.

You May Also Like: Drought May Stunt Forests’ Ability to Capture Carbon What Warming Means for 4 of Summer’s Worst Pests Warming May Boost Wind Energy in Plains States Fossil Fuels May Bring Major Changes to Carbon Dating

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.