Primeval Procreation: Strawberrylike Animal Shows Oldest Reproduction

A soft-bodied, fernlike creature reproduced in Earth's ancient oceans about 565 million years ago, making it the earliest known example of procreation in a complex organism, a new study finds.

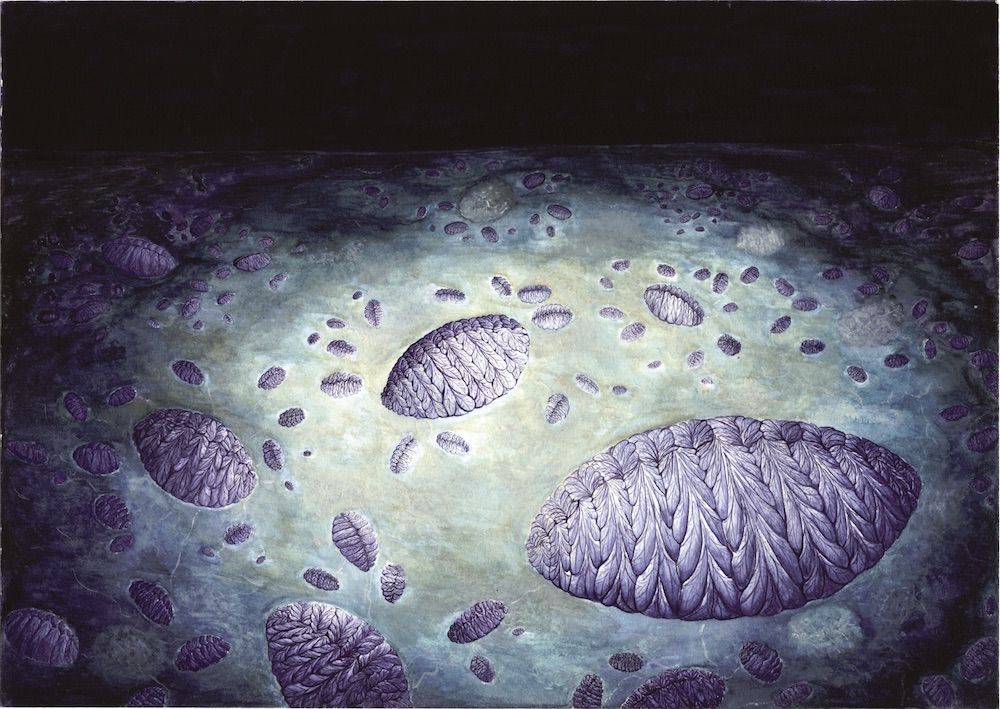

Many scientists consider the creatures, called rangeomorphs, some of Earth's first complex animals, although it's impossible to know exactly what these organisms were, the researchers said. The creatures prospered in the ocean during the late Ediacaran period, between 580 million and 541 million years ago, just before the Cambrian era. Rangeomorphs could grow up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length, but most were about 4 inches (10 centimeters) long.

What's more, rangeomorphs don't appear to have been equipped with mouths, organs or the ability to move around, and the animals likely absorbed nutrients from the water, the researchers said. However, these ancient organisms had an unusually complex reproductive strategy for their time: They likely sent out an "advance party" to settle a new neighborhood, and then colonized the new area, the researchers said. [See Photos of Ancient 'Baby' Rangeomorphs Preserved in Ash]

The findings may help scientists understand the origins of modern marine life, they said.

"Rangeomorphs don't look like anything else in the fossil record, which is why they're such a mystery," study lead author Emily Mitchell, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Cambridge's department of earth sciences, said in a statement. "But we've developed a whole new way of looking at them, which has helped us understand them a lot better — most interestingly, how they reproduced."

Mitchell and her colleagues looked at fossils of a rangeomorph known as a Fractofusus found in Newfoundland, in southeastern Canada. Like other rangeomorphs, Fractofusus was immobile, and so its fossils capture exactly where the creatures lived in relation to one another during the Ediacaran period.

Using a combination of statistical techniques, high-resolution GPS and computer modeling, the researchers found an intriguing pattern in the distribution of Fractofusus populations. The larger Fractofusus, or "grandparent" specimens, were randomly distributed around the environment, surrounded by distinctive populations of smaller "parent" and "children" Fractofusus, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These patterns of grandparent, parent and children Fractofusus are similar to biological clustering seen in modern plants, the researchers said. In fact, it's likely the creatures had two reproductive methods: The grandparents were likely born from ejected waterborne seeds or spores, whereas the parents and children likely grew from "runners," sent by the older generation, just as strawberry plants grow today.

The "generational" clustering suggests that Fractofusus reproduced asexually using runners called stolons. However, it's unclear whether the waterborne seeds or spores were sexual or asexual in nature, the researchers said.

"Reproduction in this way made rangeomorphs highly successful, since they could both colonize new areas and rapidly spread once they got there," said Mitchell. "The capacity of these organisms to switch between two distinct modes of reproduction shows just how sophisticated their underlying biology was, which is remarkable at a point in time when most other forms of life were incredibly simple."

However, Fractofusus isn’t the only organism with complex reproductive strategies reproducing during that time. A 565-million-year-old tubular invertebrate named Funisia dorothea also lived in clusters, reports a 2008 study in the journal Science. It’s possible that Funisia sent eggs and sperm into the water, a technique called spatfall that is still used by modern coral and sponges. Funisia may have also grown by using an assexual technique called budding, in which a new individual break off from the parent organism, the 2008 study found.

Rangeomorphs disappeared from the fossil record at the beginning of the Cambrian period, about 540 million years ago, making it difficult to link them to modern organisms, the researchers said. But this type of spatial analysis may help reconstruct the reproductive strategies used by other Ediacaran organisms, and help scientists understand how the organisms interacted with each other as well as their environments, the researchers said.

The study was published online today (Aug. 3) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.