No Tusks: Ancient Walrus Cousin Looked More Like a Sea Lion

About 10 million years ago, a distant cousin of the modern walrus snapped at fish as it swam near the shore of what is now modern Japan, a new study finds.

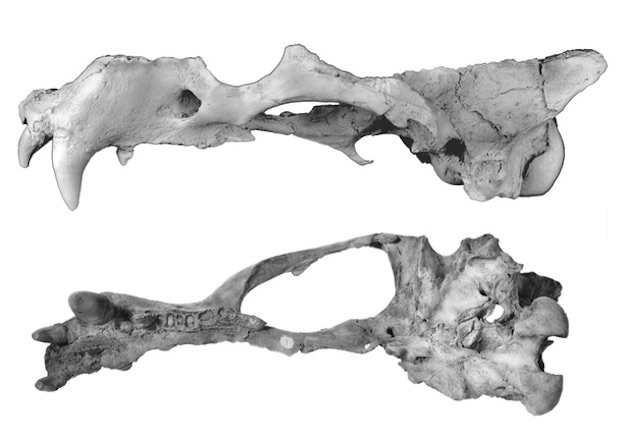

The roughly 10-foot-long (3 meters) creature didn't have tusks as walruses do today, but instead sported "moderate-sized upper canines," that measured 3.4 inches (86.3 millimeters) long, the researchers wrote in the study.

It's no surprise this ancient pinniped (a group of fin-footed, semi-aquatic animals that includes seals, sea lions and walruses) didn't have tusks, researchers said. The walrus ancestor, which weighed a whopping 1,042 pounds (473 kilograms), looked more like a sea lion. [Giants on Ice: See Amazing Images of Walruses]

"We have a really good fossil record for walruses, and we see them gradually change from these sea-lion-looking animals to the really weird-looking, giant-tusked modern walrus," said Morgan Churchill, a postdoctoral researcher of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology in Old Westbury, New York, who wasn't involved in the study. "This new fossil that's described, it just slots in really nicely into one of these small gaps that we see."

The fossil, a male young adult, was found in 1977, buried in a riverbank in Hokkaido, an island in northern Japan. Study co-author Naoki Kohno, an evolutionary biologist at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Japan, helped excavate the walrus fossil. Yoshihiro Tanaka, the study's first author and a doctoral student at Hokkaido University, joined the project in 2006 and helped finish cleaning the fossil and analyzing its anatomy, he said.

They named the new species Archaeodobenus akamatsui, meaning "ancient walrus" — in Greek, "archaios" means ancient, and Odobenus is the genus name of modern walruses. The species name honors Morio Akamatsu, a curator emeritus of the Hokkaido Museum, who assisted the researchers as they examined the fossil.

Sea change

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archaeodobenus isn't the first fossil walrus found in Hokkaido. In 2006, Kohno published a study on another newfound walrus cousin, Pseudotaria muramotoi, from the same location. A comparison of the two fossils suggests A. akamatsui split from P. muramotoi during the late Miocene in the western North Pacific Ocean, the researchers said in the study.

Changing sea levels may explain how the two species diverged, the researchers said. It appears that an ancestral population was living in the western North Pacific, but during the late Miocene, about 12.5 million to 10.5 million years ago, a sea level drop caused a change in shelf environments, the researchers said.

"That may have isolated these populations along different areas of the coast, allowing them to diverge in their [development]," Churchill told Live Science. "When sea level rose again, the amount of habitat available increased, and these two species were able to come back and contact one another."

However, "by that point, they were distinct enough that they were probably not interbreeding, as far as we can tell," Churchill said. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

It's interesting to find that two members of the Odobenidae family lived at the same time, the researchers said. Today, the modern walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) is the only surviving member of the family, but fossil finds such as these show that the family was once diverse, with at least 16 genera and 20 species.

The study is an "important contribution to the study of pinniped evolution," said Robert Boessenecker, a doctoral student of geology at the University of Otago in New Zealand, who wasn't involved in the research.

"Prior to this study, the diversity of archaic, sea lion-like walruses was always observed (or assumed) to have been low, with only one species present at a given place and time," Boessenecker told Live Science in an email. "These two species, preserved together, demonstrate that walruses diversified a bit earlier than previously thought — perhaps 3 to 5 million years earlier."

The study was published online today (Aug. 5) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Science news this week: Controversy around the dire wolf 'de-extinctions' and a 3D hologram breakthrough

Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Archaeologists may have discovered the birthplace of Alexander the Great's grandmother