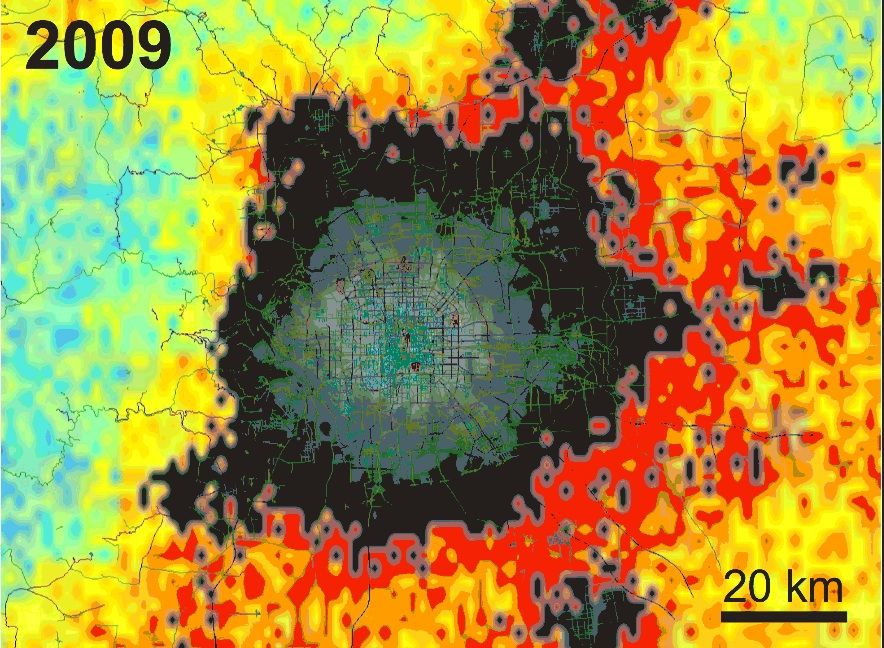

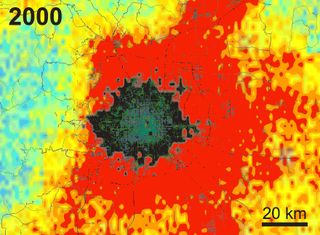

Megacity: Beijing Quadrupled in Size in 10 Years

Beijing has seen explosive growth in recent years, with the physical size of the city quadrupling in just a decade, a new study reveals. Researchers used satellite data to see how much the Chinese capital has expanded, and calculated changes in the urban environment as well.

Using NASA's QuikScat satellite, researchers at NASA and Stanford University looked at new roads and buildings that had been constructed in Beijing between 2000 and 2009. Then, they estimated how these urban developments impacted winds and pollution in the city.

Beyond the uptick in pollution from residents moving into these newly developed neighborhoods, the scientists found that the actual infrastructure — buildings, roads and other features of big cities — had consequences for the urban environment. [Human Footprints: Satellite Photos Tracking Development From Space]

"Buildings slow down winds just by blocking the air, and also by creating friction," Mark Jacobson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, said in a statement. "You have higher temperatures because covering the soil reduces evaporation, which is a cooling process."

Roofs and roads tend to become warmer during the day when the sun hits them, because they are drier than natural areas. Over the course of the decade, wind speeds were also lower by about 2 to 7 miles per hour (3 to 11 km/h), making the air more stagnant and increasing the amount of ozone pollution at ground level, the researchers said.

The scientists also found that winter temperatures in Beijing had increased by 5 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit (3 to 4 degrees Celsius), according to the American Geophysical Union.

Study co-leader Son Nghiem, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, developed a technique to quantify urban growth. The technique Nghiem employed measures microwave pulses sent from the QuikScat satellite to Earth, and records the waves that bounce back. These rebounding waves produce a pattern known as backscatter, the researchers said. Artificial, or human-built, structures tend to produce more backscatter than vegetation or soil. Larger and taller buildings also produce stronger backscatter patterns, the researchers said. As such, this technique allows scientists to chart the effects of urban growth over smaller areas, including within just a few city blocks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other satellites, including the Landsat satellites and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite, have tracked urbanization from space, but these studies were likely not as precise because they relied on visible markers (such as city lights or swaths of land cleared of vegetation) to map the extent of urban growth.

The new study was published June 19 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.