Ancient Monolith Suggests Humans Lived on Now-Underwater Archipelago

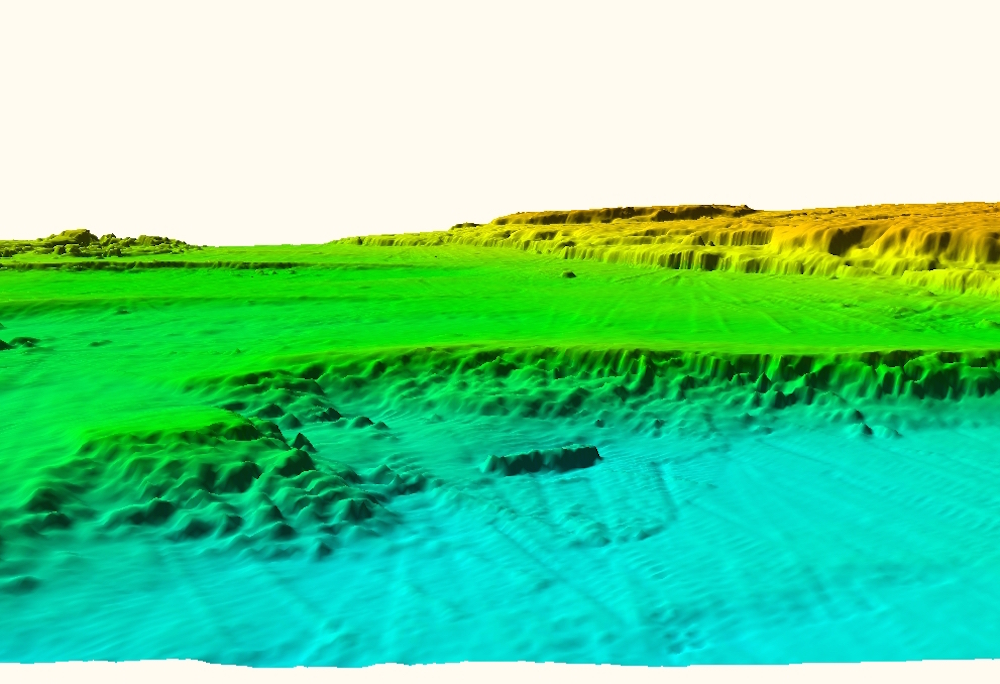

During a high-resolution mapping of the seafloor surrounding Sicily, researchers discovered an ancient treasure: a stone monolith spanning 39 feet (12 meters), resting on the bottom of the Mediterranean.

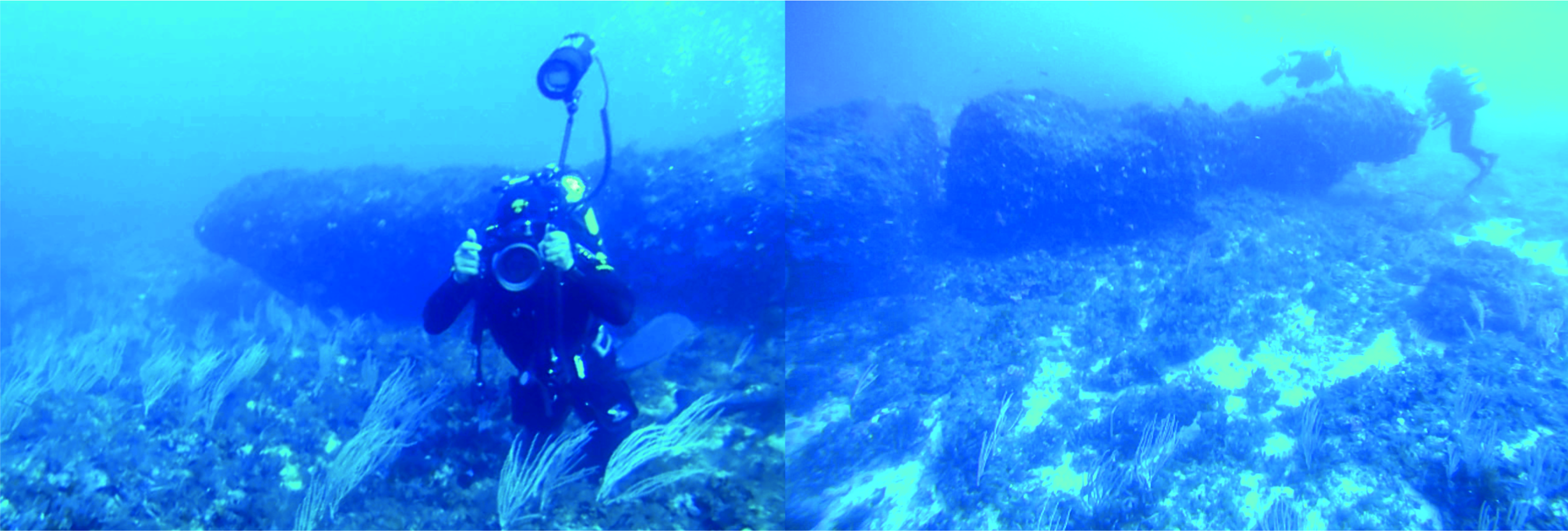

Stunned, the researchers sent down divers with cameras and video recorders to get a closer look at the monolith, which had broken into two parts. They dove 131 feet (40 m) underwater in an area called the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank, located about 37 miles (60 kilometers) south of Sicily.

"It was a great," said lead researcher Emanuele Lodolo, a staff researcher at the National Institute of Oceanography and Experimental Geophysics in Italy. "We were very excited about this discovery." [See Photos of the Mysterious Monolith Beneath the Mediterranean]

Several features suggest the monolith was man-made, possibly by people living during the Mesolithic period about 10,000 years ago, Lodolo said. It has a fairly regular shape and contains three holes with similar diameters. One hole, with a diameter of 24 inches (60 centimeters), punched all the way through the stone.

"There are no reasonable known natural processes that may produce these elements," the researchers wrote in the study, referring to the regular shape and similar size of the holes.

They suggest the complete hole held a torch, allowing the monolith to serve as a "lighthouse, to separate the settlement from the sea," Lodolo said, but it's only a guess.

What's more, the monolith doesn't match the roughly 10-million-year-old rocks on the ocean floor; rather it has a composition similar to rocks from a ridge that are found in shallow marine area, the researchers wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is one of the most important details in supporting the idea that the monolith is not made by nature or phenomena, but is man-made," Lodolo said.

Ancient archipelago

The researchers dated the stone in the monolith to the Late Pleistocene, about 40,000 years ago during the last ice age, by extracting several shell fragments from the rock and doing radiocarbon dating tests on it. It's unclear when people made the stone into a monolith, but the researchers say that varying sea levels offer a clue.

The Last Glacial Maximum began about 19,000 years ago, the researchers said. At that time, Europe was about 40 percent larger than it is now, but as the glaciers melted, sea levels rose about 410 feet (125 m) from then until present day, Lodolo told Live Science.

"This global event has led to the retreat of the coastlines, especially in lowland areas and shallow shelves, such as the Sicilian Channel," the researchers wrote in the study.

Before the sea level in the Mediterranean rose, an archipelago existed between Sicily and modern-day Tunisia. Perhaps people lived on these islands and constructed the monolith, Lodolo said.

"[The archipelago] was like a bridge between the European world and the African world," Lodolo said. "It's quite reasonable to think it was inhabited by some settlers."

The archipelago inhabitants likely came from Sicily, as land bridges existed throughout the Last Glacial Maximum between the two, according to modern-day analyses, the researchers said. Traveling from Africa to the archipelago would have been more difficult, because about 31 miles (50 km) of open sea separated them.

The archipelago disappeared underwater about 9,500 years ago, suggesting the monolith was erected before then, Lodolo said.

Advanced technology

The finding supports the idea that ancient people, who possibly lived in hunter-gatherer societies, had the capability to create monoliths, Lodolo said. It's unclear how these ancient people made the monoliths, but they likely needed advanced techniques to prepare the stone. [See Images of Stone Structure Hidden Under Sea of Galilee]

"The monolith found — made of a single, large block — required a cutting, extraction, transportation and installation, which undoubtedly reveals important technical skills and great engineering," the researchers wrote in the study. "The belief that our ancestors lacked the knowledge, skill and technology to exploit marine resources or make sea crossings, must be progressively abandoned."

The finding is "a very important discovery," said Yitzhak Paz, a researcher and excavator at the Israel Antiquities Authority, who was not involved in the study.

If the monolith is indeed man-made, it suggests, "Mesolithic people seem to have a social system that could enable them to create a very sophisticated site and erect sophisticated monuments," Paz told Live Science.

It also suggests that artifacts from ancient civilizations may be underwater, and may require divers to excavate them, both Paz and Lodolo said.

"Maybe there are other sites like this present in shallow water areas," Lodolo said. "Maybe to find the roots of civilization, it's necessary to focus research in shallow water areas that are now submerged."

The study will be published in the September issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.