El Niño Could Rank Among Strongest on Record

This year’s El Niño is poised to join the ranks of the strongest such events on record, U.S. forecasters said Thursday, with potentially significant impacts for weather across the country this winter.

“We’re predicting that this El Niño could be among the strongest El Niños in the historical record dating back to 1950,” Mike Halpert, the deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said during a press teleconference.

Whether this is good news or bad news depends on where you are: For Californians, the prospect of a top-tier El Niño boosts the hopes for a& wetter-than-average winter, which is desperately needed after four years of record-setting drought. For the Pacific Northwest, also mired in drought, El Niño usually means drier weather, though it could still be an improvement on last year.

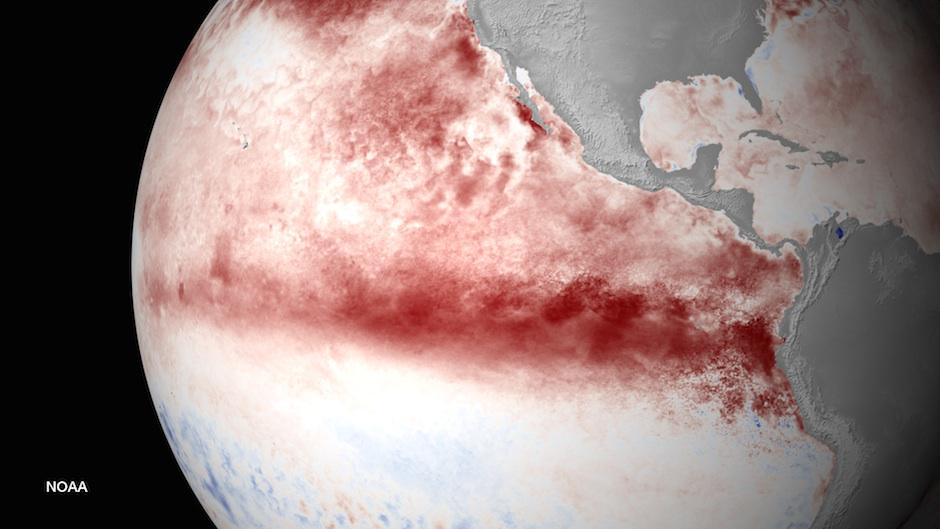

El Niño is a cyclical climate phenomenon rooted in the tropical Pacific that features a buildup of warmer-than-normal waters in the central and eastern portions of the basin. Over the last few months, those waters have been steadily heating up. In July, temperatures in a key region were more than 2°F above average, a departure that comes in second only to the blockbuster El Niño of 1997-1998, the event by which all other El Niños are judged.

How This El Niño Is And Isn’t Like 1997 El Niño Forecast Brings Calif. Hope for Drought Relief El Niño in 90 Seconds

It’s possible this El Niño, which in the latest update was called “significant and strengthening,” could reach more than 3.5°F above normal in this ocean region, “a value that we’ve only recorded three times in the last 65 years,” Halpert said. That threshold was reached during the 1997-1998 event, as well as those from 1982-1983 and 1972-1973.

But El Niño isn’t just about a feverish ocean — what matters to most people are the impacts to weather that those warmer waters can usher in around the world. The shift of warm water from west to east in the tropical Pacific causes changes in the circulation of the atmosphere overhead. These shifts in turn create a domino effect of altered atmospheric patterns across the globe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the U.S., these impacts come about because of a split in the winter jet stream, the river of air that guides storms over North America. The jet breaks up into southern and northern strands, with the former typically flowing over Southern California and the later up into Alaska.

For Southern California, that means higher odds of above average winter precipitation. This was certainly the case in the 1998 and 1983 El Niños, but higher odds don’t mean a rainy winter is 100 percent certain. There have been other El Niño events when California was drier than normal.

“None of the typical impacts are ever guaranteed,” Halpert said.

Still, the boosted odds are potentially welcome news to a state that is four years into a record-setting drought, as it could begin the slow climb out of the precipitation hole. But they can also come with serious downsides, such as major flooding and landslides, as happened with the 1998 event.

Also, the link between more precipitation and El Niño really only holds for Southern California, while it is the northern half of the state where the main reservoirs, supplied by mountain snowpack, are situated. There’s no knowing whether the winter will bring the healthy snows needed to replenish those water stores.

Some of that will depend on winter temperatures, which were unusually high across the West last winter, causing precipitation to fall as rain, not snow, and leaving states with record low snowpacks.

Those elevated temperatures — which made winter feel more like spring — were the result of a persistent high-pressure pattern that also helped form a large pool of warm water off the West Coast, which some scientists dubbed “the blob.”

El Niño could actually knock out the high-pressure pattern and with it the unusually hot weather, Cliff Mass, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington, said. This already seems to be happening, he added.

What this might mean for the Pacific Northwest’s winter is a bit unclear. El Niño tends to bring warmer and drier conditions to the region, which has water managers preparing for another dry winter with a low snowpack. But if it knocks out the relentless pattern of recent years, it could actually make this winter better than last with perhaps more snow, even if it isn’t as much as would fall without El Niño in place.

“I’m actually looking forward to next year” being better than this year, Mass said.

How exactly El Niño, the blob and the vagaries of winter weather will come together to influence temperatures, rain and snow are “questions that don’t have answers at this point,” Halpert said. “We just don’t know.”

You May Also Like: Scientists Foresee Losses as Cities Fight Beach Erosion Surge In ‘Danger Days’ Just Around The Corner Underground Desert Aquifers Could Hold Missing Carbon Heat Continues to Roast West, Fueling Drought, Blazes

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.