Ghostly Particles Detected Beneath Earth

Using giant vats of organic liquid buried under a mountain in Italy, scientists have shed new light on the origins of ghostly particles known as neutrinos generated by the Earth.

This research could yield insights into what radioactive elements lie deep inside the Earth and how they influence the churning of the Earth's innards, researchers added.

Neutrinos are subatomic particles generated by nuclear reactions and the radioactive decay of unstable atoms. They are vanishingly tiny — 500,000 times lighter than the electron.

Neutrinos possess no electric charge and only rarely interact with other particles, so they can slip through matter easily — a light-year's worth of lead, equal to about 5.8 trillion miles (9.5 trillion kilometers) would only stop about half of the neutrinos flying through it. Still, neutrinos do occasionally strike atoms. When that happens, they give off telltale flashes of light, which scientists have previously spotted to confirm the particles' existence.

The decay of radioactive elements within the Earth sends out streams of neutrinos that scientists can detect on the Earth's surface. These "geoneutrinos" can offer novel insights into the planet's interior. For instance, although much of the Earth's internal heat is left over from its violent creation, some of it also comes from the decay of radioactive elements. But no one is certain how much. Geoneutrinos can reveal what different radioactive isotopes are scattered throughout Earth's interior and how their heat influences geological activity such as the flow of rock and any resulting earthquakes and volcanoes. [5 Mysterious Particles That May Lurk Beneath Earth's Surface]

"Heat sources will produce movements of large amount[s] of material," said study co-author Aldo Ianni, an experimental particle physicist at Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy.

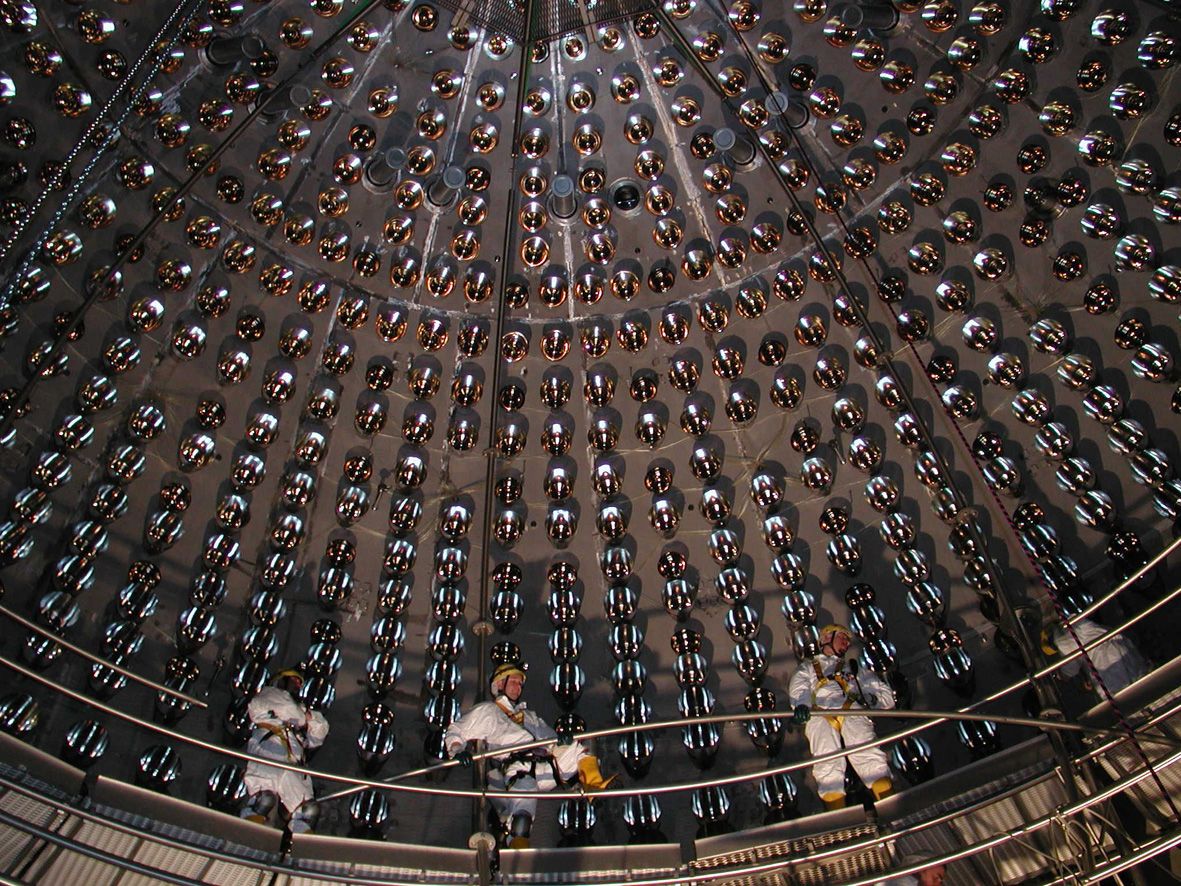

To detect geoneutrinos, Ianni and his colleagues employed the Borexino neutrino detector at the Gran Sasso National Laboratory. This instrument uses more than 2,200 sensors to spot the flashes of light that neutrinos give off in the exceedingly rare instances in which they interact with nearly 300 tons of a special organic liquid. All of this is housed at the center of a large sphere surrounded by 2,400 tons of pure water about 1 mile (1.5 kilometers) under the Apennine Mountains.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers now report the most extensive set of data yet collected for geoneutrinos. After analyzing 2,056 days of Borexino measurements, they detected about 24 geoneutrinos. They detailed their findings online Aug. 7 in the journal Physical Review D.

Analysis of the energies of these geoneutrinos suggests about 11 came from the Earth's mantle (the hot, rocky layer sandwiched between the core and crust) and about 13 came from the crust, Ianni said. The geoneutrinos the scientists have detected so far suggest that about 70 percent of the heat in the Earth's interior is due to radioactivity, although there is a great deal of uncertainty in that number, Ianni told Live Science. In order to get more definitive results, they would need to gather data for nearly another 17 years, he said.

Ianni said that in the future, scientists could place multiple geoneutrino detectors around the Earth. This could help researchers detect where radioactive elements spread throughout the Earth's interior, to help pinpoint how their heat influences the Earth's internal activity.

Follow Live Science@livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular