Researchers have deciphered the structure of a harpoon-like protein some viruses use to enter cells and begin infection.

The protein is known as fusion (F) protein and is found on the outer surface of parainfluenza virus 5, a so-called "enveloped" virus that fuses its membrane with the membrane of its host cell before infection.

Once the membranes are fused, the virus dumps its genetic content into the healthy human cell's interior, hijacking the cell's replication machinery to clone itself.

Enveloped viruses are responsible for a wide variety of human diseases, including mumps, measles, HIV, SARS and Ebola. The finding could help researchers develop drugs that prevent infection by blocking viral entry into cells.

The researchers crystallized the F protein and used x-ray crystallography to determine its three-dimensional structure. Doing so revealed a hydrophobic (meaning water-repellant) tip that allows the viral harpoon to latch on more securely to the cell membrane, which is also hydrophobic. It also provided researchers with more insight into the dramatic structural change that the F protein undergoes while performing its task.

A three-dimensional model of the HIV virus. Image Courtesy 3DScience.com

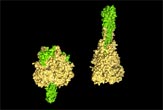

When not in use, the F protein looks like a mushroom and its hydrophobic tip is folded into a compact form, safely hidden inside the cap. When the virus comes into contact with a target cell, the cap unfurls and the hydrophobic tip is hurled like a harpoon into the cell's outer membrane.

The F protein then brings the virus and the cell together so their two membranes can merge. It does this by collapsing back on itself like a metal rod bent so that its ends meet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The collapse of the protein acts like a hairpin that snaps together and brings the two membranes together to make them fuse," said Theodore Jardetzky, a structural biologist from Northwestern University and the study's principle investigator.

The research, led by Hsien-Sheng Yin of Northwestern University, is detailed in the Jan. 5 issue of the journal Nature.

- FLU FEARS: A Special Report

- Huge New Virus Defies Classification

- Scientists Recreate 1918 Flu Virus From Scratch