IceCube Photos: Physics Lab Buried Under Antarctic Ice

A gigantic observatory called IceCube lurks beneath Antarctic ice at the South Pole, where detectors scan the cosmos for ghostly, near-massless neutrinos. These "high-energy astronomical messengers," as IceCube collaborators call them, shed light on some of the most violent happenings in the universe, including exploding stars, gamma-ray bursts, and processes that involve black holes and neutron stars. Here's a look at the chilly lab and some of its findings.

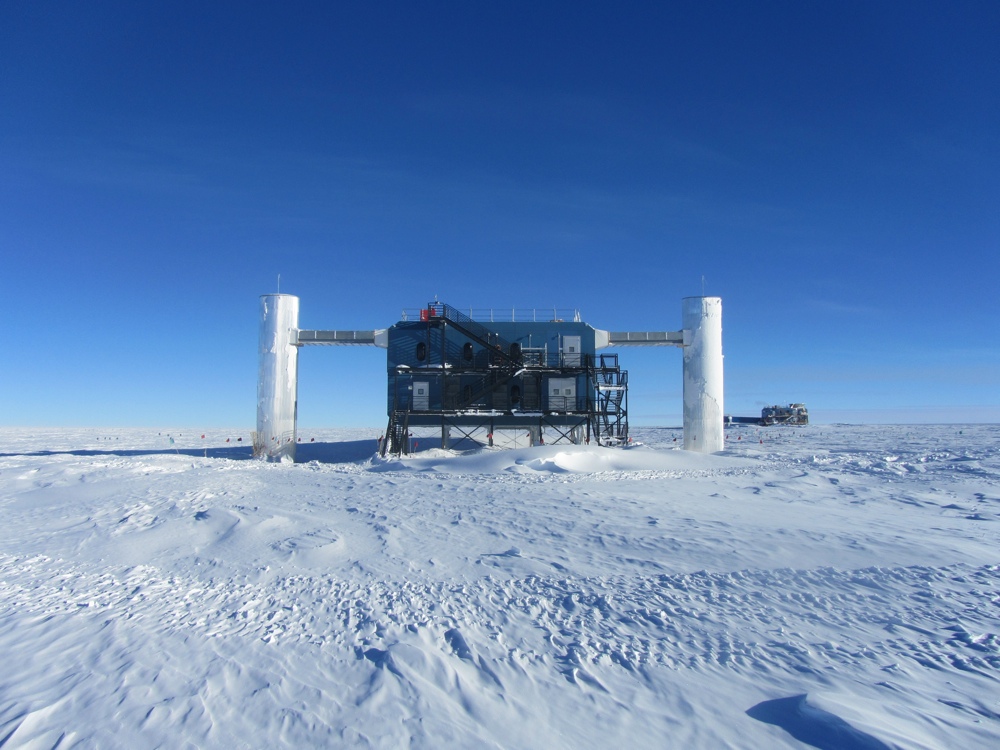

Block of ice

The IceCube Observatory resides at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. The network of people who make the lab run (called the IceCube Collaboration) includes about 300 physicists hailing from 45 institutions and 12 countries. (Photo Credit: Dag Larsen, IceCube/NSF)

Gorgeous strings

The part of the observatory that's buried beneath the ice holds 5,160 sensors called digital optical modules (DOMs). These sensors are attached to "strings" frozen into 86 boreholes that are spread out over a cubic kilometer (0.24 cubic miles) at depths from 4,800 to 8,000 (1,450 to 2,450 meters). Here an artistic impression of the DOMs. (Photo Credit: Jamie Yang, IceCube Collaboration)

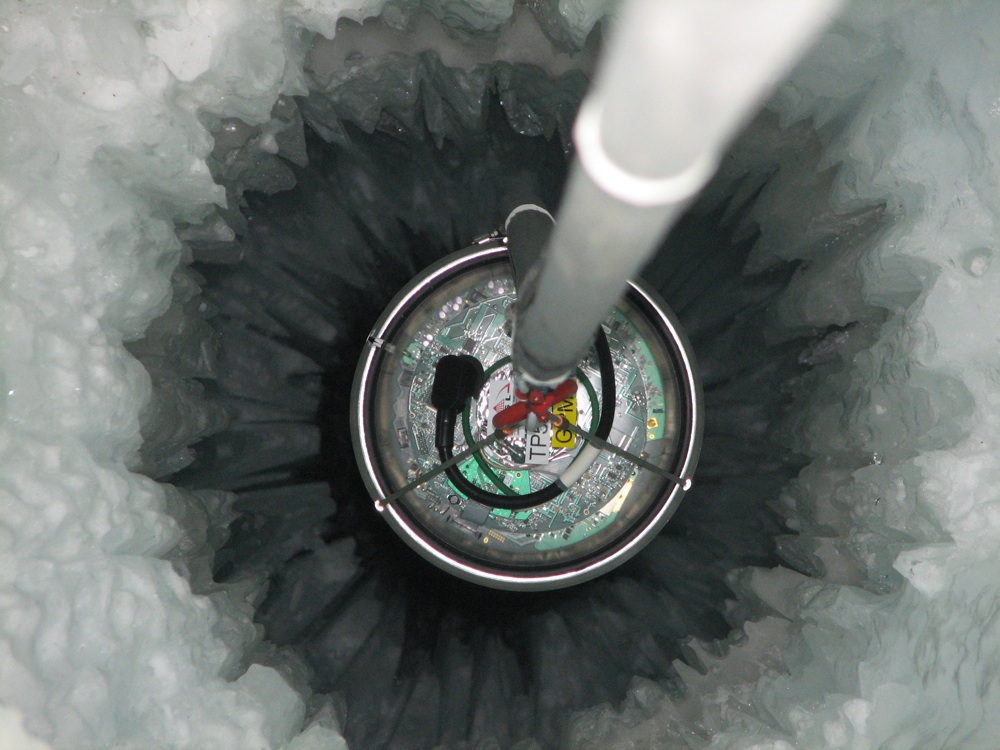

It's freezing!

It took about 11 hours to deploy each of the 86 "strings," during which time 60 DOMs were quickly installed into each — the scientists had to be quick and get it done before the ice froze completely around the sensors. (Photo Credit: IceCube/NSF)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

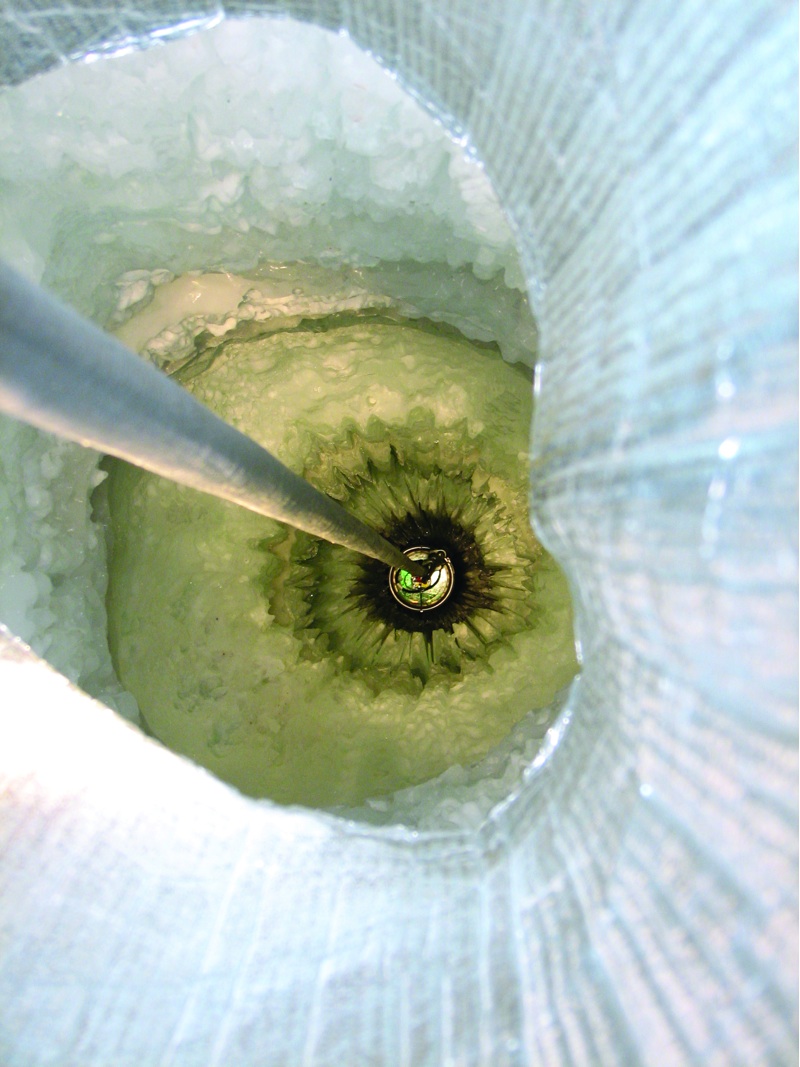

Spacing sensors

The strings of sensors, shown here, were spaced about 55 feet (17 meters) apart. (Photo Credit: Jim Haugen, IceCube/NSF)

Leaving a mark

The team of scientists, engineers and drillers who deployed the observatory in December 2010 signed the last sensor before it was buried beneath a mile of Antarctic ice. (Photo Credit: Robert Schwarz, NSF)

DESY DOM

The sensors (digital optical modules) were put together at three different locations. Here, DOMs are prepared for final assembly at DESY (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron) in Germany in 2004. (Photo Credit: DESY)

Sista

Here the last DOM, which was assembled at Stockholm University. The collaborators donned each DOM with a name — This one is called "sista," which means last in Swedish. (Photo Credit: Stockholm University)

Stunning stars

Southern lights

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.