Plague Cases in California: What's Behind the Rise?

After nearly 10 years without any cases of plague, California has seen two people contract the age-old illness already this summer. But what could be behind the sudden return of plague to the state?

Experts say it's hard to know why there are more cases of plague in California this year than in recent years. A number of factors — including the behavior of people or rodents, or even the California drought — could play a role in the cases of this bacterial infection.

On Tuesday (Aug. 18), California officials announced that they were investigating a case of plague in a Georgia resident who visited Yosemite National Park this month. At this point, the patient is presumed to have the plague, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is still conducting tests to confirm the illness.

In July, another visitor to Yosemite — a girl from Los Angeles County — was also diagnosed with plague after her visit to the park. The girl is recovering, health officials have said.

Before these two cases, the last reported cases of plague in California occurred in 2006. [Pictures of a Killer: A Plague Gallery]

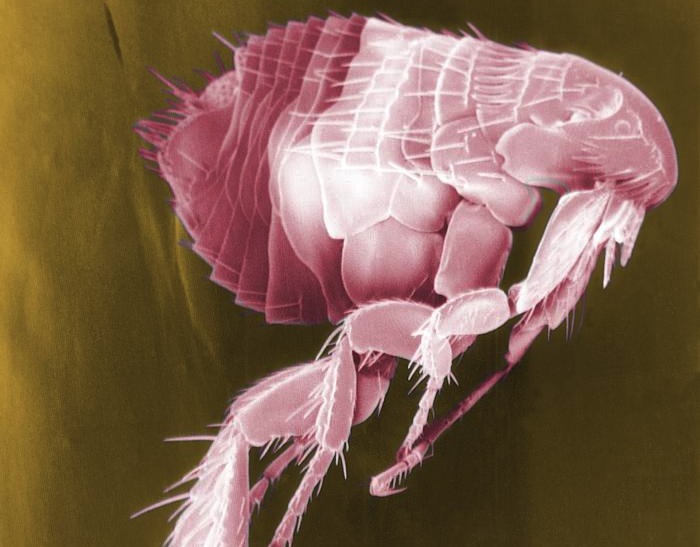

Although plague is rare in California, it's not unheard of, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious-disease specialist and a senior associate at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Center for Health Security. Rodents in California, as well as those in other Western states, are known to carry the fleas that can transmit plague.

"These cases are occurring in locations where we know that plague exists in the [rodent] population," Adalja told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There have been 42 cases of plague in California since 1970, and nine were fatal.

Factors such as the amount of interaction between people and rodents (for example, people feeding the animals, or staying in cabins built in a new area), and the adventurousness of rodents, as they make their way into campgrounds, could affect people's risk of plague.

While there haven't been any studies looking to see if the California drought is affecting plague risk, past research has shown that weather can affect plague transmission, said Dr. Bruno Chomel, a professor at the University of California at Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine.

Chomel speculated that if the drought is limiting food options for rodents, the animals may be seeking food in camp grounds.

In addition, warmer temperatures are favorable for flea activity, and if there is an increase in the flea population, the insects may be looking for more hosts, Chomel said.

Another factor that affects plague transmission is the type of rodents that are around. Small rodents such as mice are usually less susceptible than larger rodents are to becoming severely ill with plague, but if squirrels or chipmunks become infected, they usually die, Chomel said. So if plague-infected fleas jump from small rodents to squirrels, and then the animals succumb to the disease, the fleas will need to find new hosts.

Despite the recent increase in plague in California, the number of plague cases in humans seen so far in the United States this year is not out of the norm. Plague cases occur sporadically in the United States — between 1970 and 2012, an average of seven plague cases occurred yearly, according to the CDC. The disease is usually treatable with antibiotics if it is caught in the early stages.

The plague is caused by bacteria called Yersinia pestis, and the disease is perhaps best known for causing the Black Death in Europe, in the 1300s. Researchers estimate that 75 million people died, or between 30 percent and 50 percent of Europe's population.

So far this year, there have been two deaths from plague in Colorado, in addition to the two California cases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.