Women's Libido Pill Faces Skepticism After Approval

Some health professionals are reacting with more enthusiasm than others about the first approved drug aimed at increasing women's sexual desire.

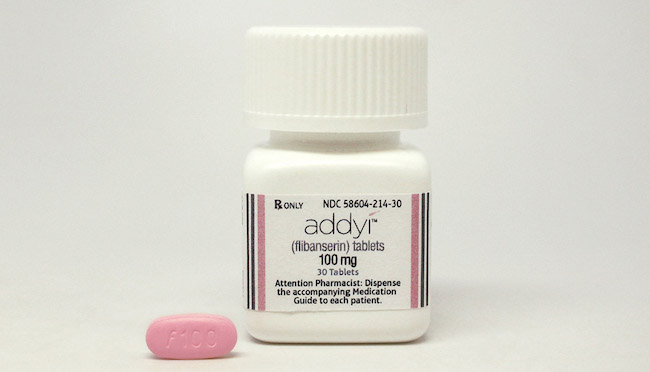

Known generically as flibanserin and sold under the brand name Addyi, the medication could be prescribed as early as Oct.17, said Sprout Pharmaceuticals, the company that developed the so-called "little pink pill."

Many have compared Addyi to Viagra, the medication for men with erectile dysfunction that increases blood flow to the penis. But the new pill for women aims to boost women's libidos by affecting levels of brain chemicals, rather than blood flow. It doesn't get ladies physically ready for sex; rather, it purports to get them mentally ready to do the deed by targeting neurotransmitters in the brain linked to desire, appetite and other sex-related emotions. [51 Sultry Facts About Sex]

But some experts aren't sold on this neurological approach to curing low libido. The problem with focusing solely on neurotransmitters' role in sex drive is that a woman's desire to have sex isn't linked only to chemicals in the brain, said Kristen Carpenter, a psychologist and director of Women's Behavioral Health at The Ohio State University's Wexner Medical Center.

Sexual desire is a "multifaceted phenomenon," Carpenter said.

And although Addyi may help a subset of women, it won't improve the sex lives of all women who have low libido, said Carpenter, who provides therapy for many women with low libido.

"I don't think this will be a magic bullet," she said. "Sexual desire is a largely psychological phenomenon, which is why it's important that a [medication] that acts centrally on the brain be a part of treatment. But it is a nuanced experience, and a pill only addresses one piece of that."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not for everyone

Sprout Pharmaceuticals doesn't claim that Addyi will amp up the libidos of all women, just certain women. The FDA approved the drug specifically for use by premenopausal women who have been diagnosed with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), a condition that means they not only have low levels of desire, but also feel bothered by it.

According to the company, approximately one in three women in the United States has low sexual desire, and about one in 10 women feels distressed about it. That translates to 16 million ladies who potentially have HSDD, and the company says that Addyi could potentially help the 4.8 million of those women who are premenopausal.

Doctors screen women for HSDD using a test that has five basic questions, but in order to be diagnosed with the condition, all other potential causes of low libido must first be ruled out, said Dr. Risa Kagan, an obstetrician gynecologist and clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

The list of other potential causes of low sex drive includes depression, use of certain medications (like antidepressants and painkillers), alcohol and drug use, pregnancy, pain during intercourse, stress, and dissatisfaction with one's partner. These must all be crossed off before a diagnosis of HSDD can be made.

Still, other factors that contribute to low desire might not get ruled out during the screening process for HDSS. For example, aging, lack of sleep and headaches have all been shown in studies to decrease sex drive in women, and none of these causes of low libido is explicitly included in the screening questionnaire.

Carpenter said figuring out which women actually have HSDD is going to be tricky for doctors, who often fail to spend more than a few minutes with a patient at a time. In her own psychology practice, Carpenter said, she has assumed some patients had HSDD, but later learned (typically during therapy) that their low libido was actually caused by sexual trauma.

"That is something this medication won't help with," she said. If a doctor does not develop a relationship with a patient, or thoroughly learn their history, they may not know whether there is another cause of a woman's low libido.

Indeed, Kagan, who was an investigator for clinical trials of flibanserin when the drug was in development, said that screening a woman for HSDD can take a long time — about 90 minutes, in her experience.

In an effort to help doctors diagnose women, Sprout has created a presentation about the condition that doctors must watch, and pass a test on, before they can prescribe or dispense Addyi , Kagan said.

But there's one more problem: Not all medical professionals agree that HSDD is a condition that needs to be treated.

Dysfunctional disorder

"Sex is a very emotional response for women, and so we've gotten to the point where we're developing emotional-response drugs to get women to have sex, and that's a slippery slope," Dr. Elizabeth Kavaler, a urologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, told Live Science.

Not being in the mood for sex, or not being that into sex in general, is perfectly normal, Kavaler said. Carpenter made a similar point, saying that low libido is not necessarily a medical condition that needs to be treated with medication.

"Maybe, for some subset of people, medication might be helpful. But it's also the case that desire just doesn't fall out of the sky," said Carpenter, who added that she often instructs women on the other ways to increase sex drive without medication (like slipping on some sexy underwear or engaging in sexual fantasy).

Kagan said that women who don't want to have sex — because they are exhausted, or have a headache or just don't like having sex — should not be prescribed Addyi. A lack of desire is just one element of HSDD, the condition that Addyi is designed to treat.

"[HSDD] is a state of mind. It's somebody who had an appetite, and they want to want it back again," she said. Brain-imaging studies, including a small one published in the journal Neuroscience in 2009, have suggested that women with HSDD are wired a bit differently than women without the condition, Kagan said.

The 2009 study showed that the brains of women with no history of sexual dysfunction had a different way of processing "arousing stimuli" than the brains of women who had HSDD. Among the 36 participants, the researchers found that these two groups varied in how they remembered past erotic events.

But more research is needed in this area in order for scientists to figure out just how desire works in women's brains. If researchers can get to the bottom of the mystery, then the little pink pill could become one of many treatment options available for women who want to increase their libidos.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.