The consequences of global sea level rise could be even scarier than the worst-case scenarios predicted by the dominant climate models, which don't fully account for the fast breakup of ice sheets and glaciers, NASA scientists said today (Aug. 26) at a press briefing.

What's more, sea level rise is already occurring. The open question, NASA scientists say, is just how quickly the seas will rise in the future.

Rising seas

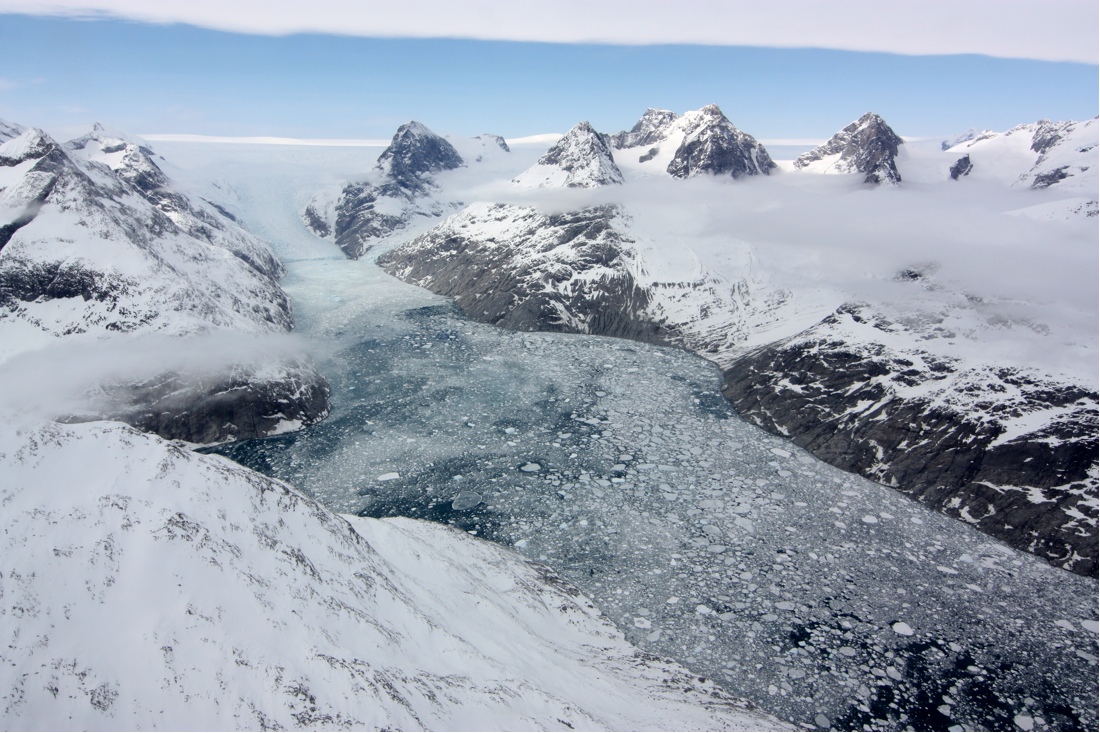

The current warming of the seas and the associated expansion of their waters account for about one-third of sea level rise around the world. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

"When heat goes under the ocean, it expands just like mercury in a thermometer," Steve Nerem, lead scientist for NASA's Sea Level Change Team at the University of Colorado in Boulder, said in the press briefing.

The remaining two-thirds of sea level rise is occurring as a result of melting from ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica and mountain glaciers, Nerem said.

Data collected by a cadre of NASA satellites — which change position in relation to one other as water and ice on the planet realign and affect gravity's tug — reveal that the ocean's mass is increasing. This increase translates to a global sea level rise of about 1.9 millimeters (0.07 inches) per year, Nerem said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unpredictable pace

But the speed of sea level rise is an open question.

"Ice sheets are contributing to sea level rise sooner, and more than anticipated," said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine, and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

That's because people have never seen the collapse of a huge ice sheet and therefore don't have good models of the effects, Rignot said.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an international organization created by the United Nations that produces climate change models, has predicted that sea levels could rise as much as 21 feet (6.4 meters) in the next century if global warming continues unabated.

But even that worst-case scenario may not capture the risk, Rignot said. That's because the IPCC models only take into account temperature changes at the surface of glaciers, but not the rapid melting that occurs when glaciers calve and break up into the ocean, Rignot said.

In addition, much of glaciers' melting occurs at deep, undersea ice canyons. Warmer water is salter and therefore heavier. That means it sinks into the deeper layers of the ocean, and the contrast between this warm water and the undersea ice canyons contributes an unknown but substantial amount of sea level rise, said Josh Willis, an oceanographer at JPL in Pasadena, California.

When the massive Jakobshavn glacier in Greenland calved earlier this summer, it moved 4.6 square miles (12 square kilometers) of ice in one day, Rignot said. [See Photos of Greenland's Melting Glaciers]

If the Jakobshavn glacier had melted completely, "it contains enough ice to raise global sea level by half a meter — just this one glacier in Greenland," Rignot said. If all the land ice on the planet were to melt, it would raise sea levels about 197 feet (60 m), he added.

Some of the melting that has already occurred is likely irreversible, and could take hundreds of years to reverse, Rignot said.

American impact

While global sea levels have risen about 2.75 inches (7 centimeters) over the past 22 years, the west coast of the United States has not seen much of a rise in ocean levels. That's largely because of a long-time-scale weather pattern called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which is masking the global effect. That, however, could reverse in the coming years, Willis said.

"In the long run, we expect the sea levels on the west coast to catch up to global mean and even exceed the global mean," Willis said.

Florida is also particularly vulnerable to sea level rise because its porous soil allows more seawater intrusion than does the soil in other coastal areas, Willis said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.