Ouch! Volunteers Get Tick Bites for Science

We all know that some ticks bite, but just how eager certain species are to feed on humans, and how quickly people react to their bites, is less clear in some cases. A new study attempted to answer these questions for the lone star tick, by having the bugs feed on the arms of volunteers.

Lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) are common in the Southern United States, although they are also found in the Eastern and South-Central U.S., and they are known to bite people. But until now, no study had examined their bites in a laboratory setting, where researchers can be sure that the bites came from a lone star tick, and can control how long the ticks feed, said study researcher Jerome Goddard, an entomologist at Mississippi State University.

In the new study, 10 people — including Goddard and his wife — volunteered to let the ticks feed on them for 15 minutes. Ten ticks were placed on the inside of a bottle cap, and each participant had two bottle caps secured to his or her body (one on each arm), for a total of 20 ticks per participant. All the ticks used in the study were certified as disease-free by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

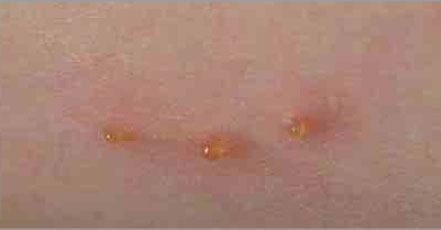

Eight of the participants had ticks attach to their arm during the 15-minute feeding period, and five participants developed raised itchy bumps in reaction to the tick bites, within 48 hours. One participant had an immediate reaction — a flat, raised area appeared as soon as researchers removed the bottle cap.

"It surprised us in how fast some people reacted," Goddard said. It was thought that reactions to tick bites usually take a few days to develop, but the new findings show that "at least some people react vividly, in a pretty short period of time," Goddard told Live Science.

The participant who had the immediate reaction went on to develop itchy, fluid-filled bumps known as "weeping" vesicles.

The findings "reinforce that this is a very aggressive tick — they attached and fed quickly, and they can produce all kinds of allergic reactions in people," Goddard said. [10 Important Ways to Avoid Summer Tick Bites]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings may help doctors to diagnose the cause of mysterious bites in people living in areas where these ticks are common, Goddard said.

In addition, the findings may be useful for future studies on disease transmission from these ticks, Goddard said. Scientists now know that these ticks can bite quickly, and future studies should also look at whether any diseases carried by the ticks are also transmitted quickly.

Bites from lone star ticks can cause a condition called southern tick-associated rash illness, a circular rash that typically goes away after antibiotic treatment. But studies suggest these ticks may also carry the recently discovered heartland virus. It's also thought that bites from the lone star tick can cause some people to develop an allergy to red meat.

The new study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 26) in the journal JAMA Dermatology.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents