Photos: Primordial Sea Scorpion Was a Top Predator

Fossils of 460-million-year-old eurypterids (sea scorpions) were uncovered underneath the flowing waters of the Upper Iowa River. Researchers named the newly discovered species Pentecopterus decorahensis after an ancient Greek warship called the "penteconter." During the Ordovician period, these creatures likely scuttled along the seafloor as juveniles, but grew up to be top predators swimming around the ocean. [Read the full story on the ancient sea scorpion]

Sea scorpions

This illustration shows two adult sea scorpions that lived during the Ordovician period about 460 million years ago. (Image credit: Patrick Lynch | Yale University)

Excavation site

The Iowa Geological Survey discovered the fossils during a mapping project of the Upper Iowa River. Researchers subsequently found at least 20 P. decorahensis individuals, and had to dam the river to safely remove the specimens. (Image credit: Iowa Geological Survey.)

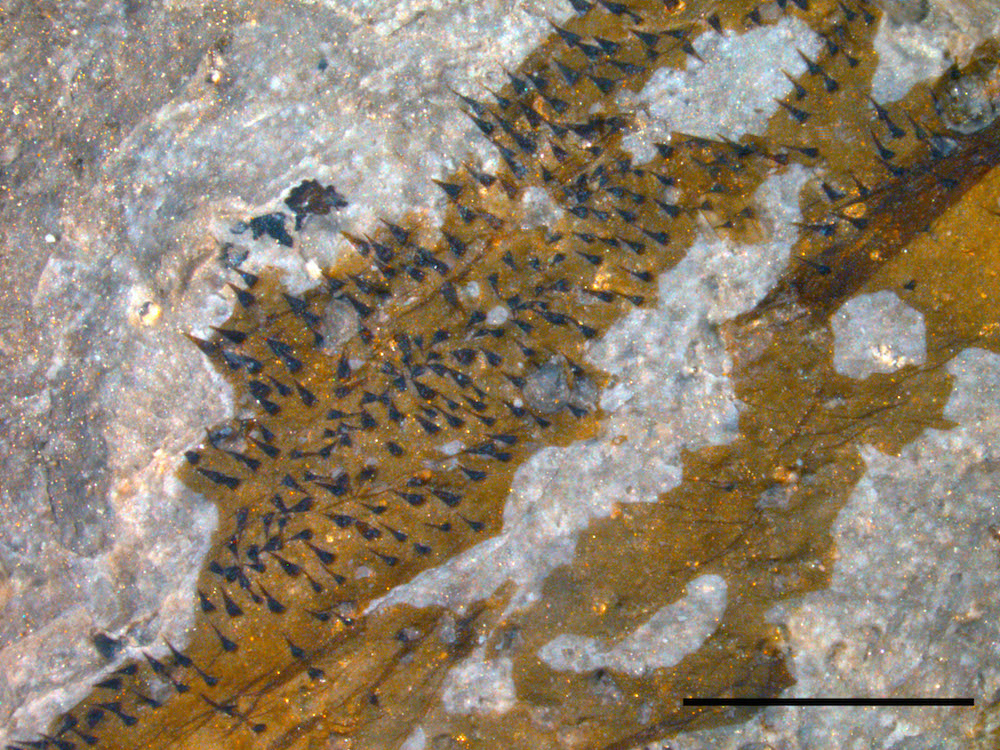

Tiny hairs

The fossil shows tiny P. decorahensis hairs. The scale bar represents 0.04 inches (1 millimeter). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

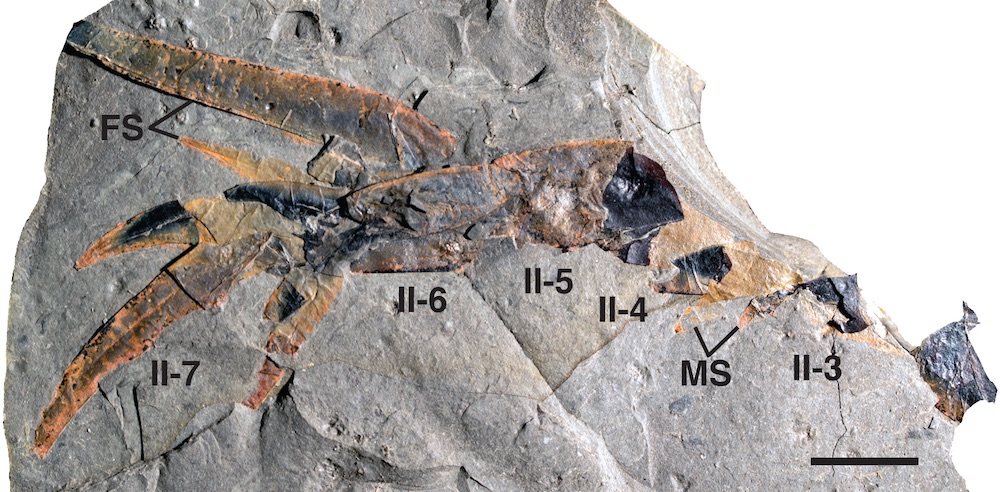

Amazing appendages

The appendages of a juvenile P. decorahensis. Researchers suspect that its appendages changed as the creature aged. First, it likely walked along the bottom of the ocean, but later, as its appendages grew, it was likely able to swim after prey. The scale bar represents 0.4 inches (1 centimeter). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

Sharp serrations

This P. decorahensis appendage has an enlarged spine and a serration. The scale bar represents 0.4 inches (1 cm). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

Movable parts

This appendage shows movable and fixed spines. The scale bar represents 0.4 inches (1 cm). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

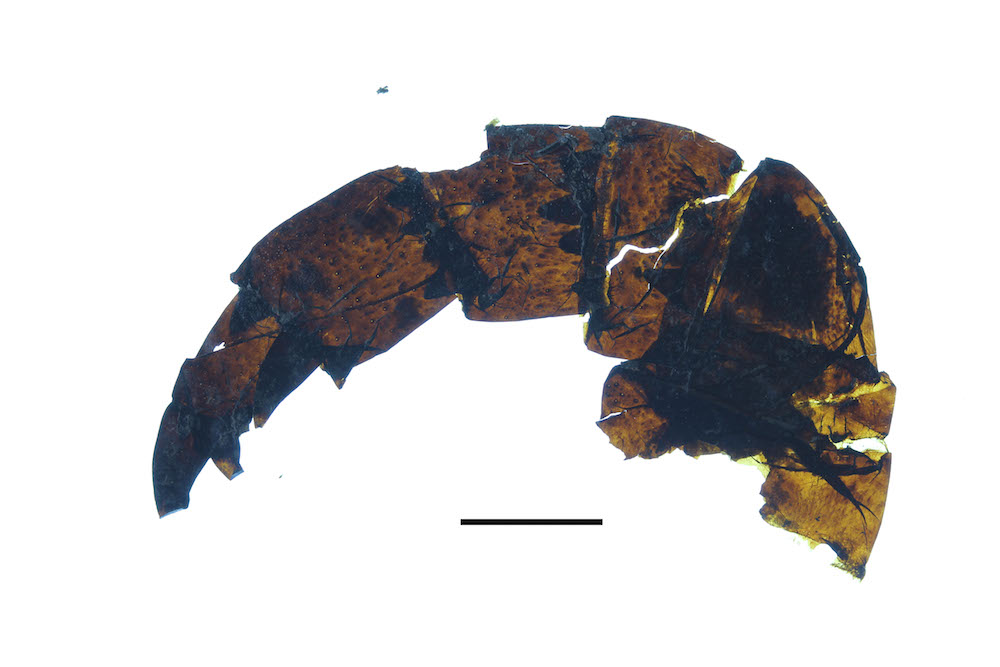

Curled leg

A leg of a P. decorahensis. The scale bar represents 0.4 inches (1 cm). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

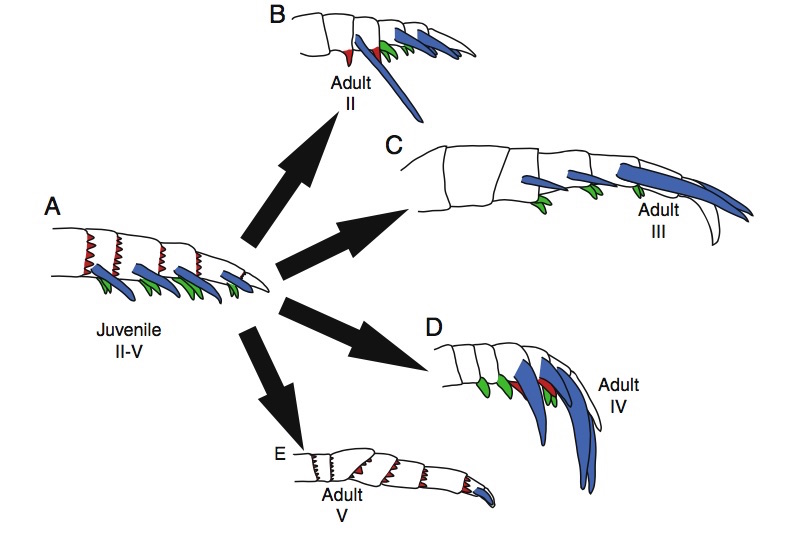

Appendage spines

The researchers found remains of both juvenile and adult specimens. Notice how the spines differ in the young versus the adult individuals. Similar structures are color-coded: Red shows distal denticulations (small notches pointing away from the body); green shows movable ventral (underside) spines; and blue shows fixed lateral spines (on the creatures' sides).

As they age, "the spines get really long," said study lead researcher James Lamsdell, a postdoctoral associate of paleontology at Yale University. "They could have been used for catching larger prey." (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

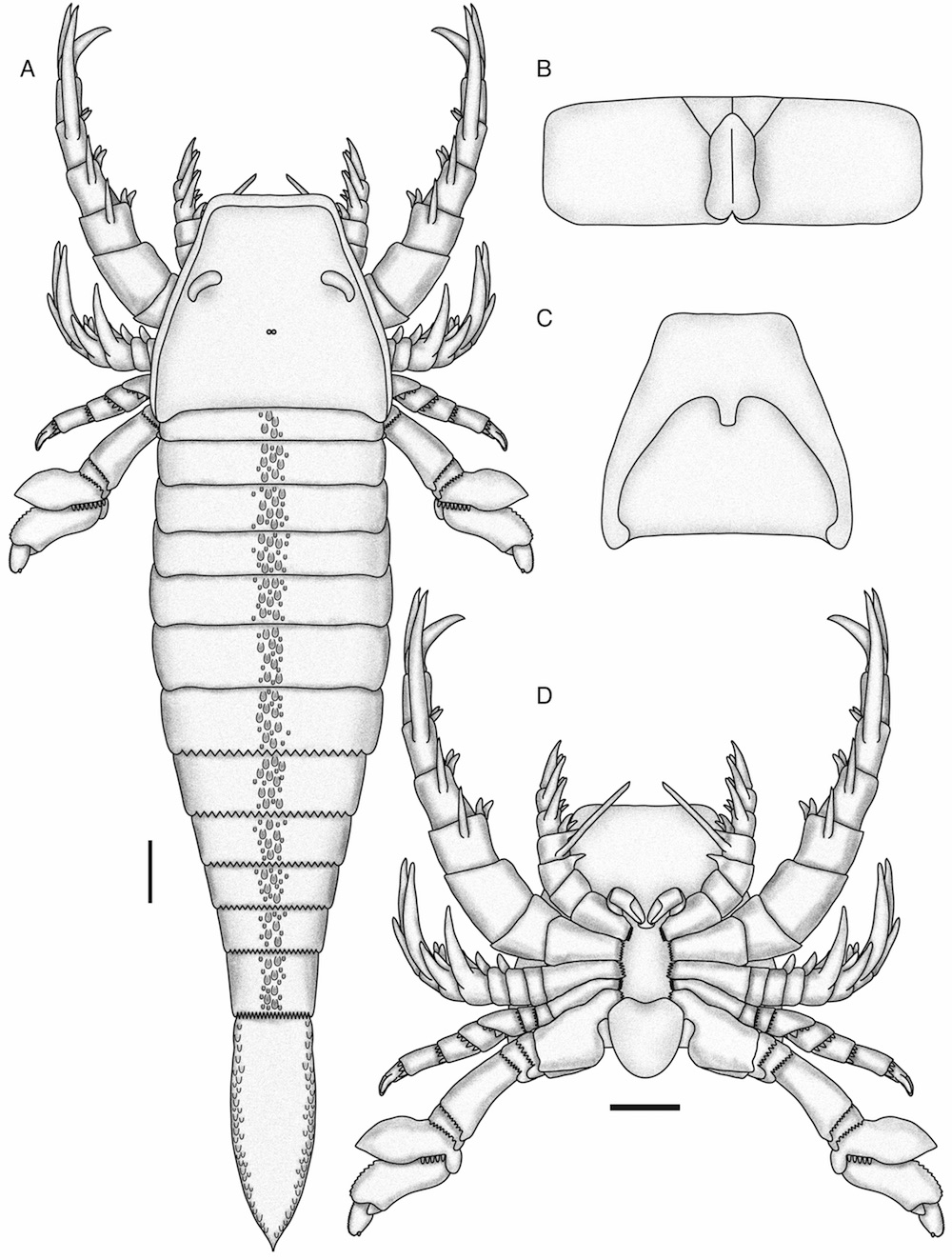

Adult eurypterid

A reconstruction of an adult P. decorahensis. The different perspectives show the dorsal view (A), genital covering (B), ventral view of the hard upper shell (C) and the appendages, as seen from the back looking toward the front (D). However, the fossil findings were incomplete, so the portion of the illustration showing the top of the creature's head is hypothetical. The scale bar represents 4 inches (10 cm). (Image credit: James Lamsdell.)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.