Why Creative Geniuses Are Often Neurotic

Sir Isaac Newton formulated the laws of gravity, built telescopes and delved into mathematical theories. He was also prone to bouts of depression and once suffered a mental breakdown.

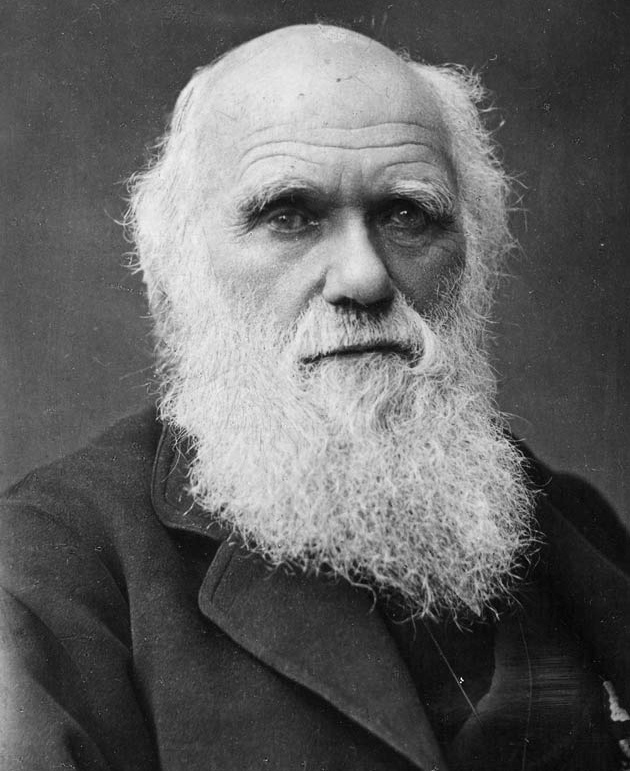

In this sense, Newton was like many other creative, driven individuals. Charles Darwin, for example, struggled with nausea and gastrointestinal distress in response to stress, so much so that modern psychologists have suggested that he may have had a panic disorder. Winston Churchill referred to his dark moods as his "black dog," leading to speculation that he might have had episodes of depression.

Whatever the truth behind these prominent men's mental health, multiple studies have found a link between creativity and neuroticism — a tendency toward rumination and negative thinking. Now, British researchers have proposed a possible reason for the connection: Creativity and neuroticism could be two sides of the same coin. [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

Overthinking it

Neuroticism is a personality trait that lends itself to worry, anxiety and isolation. Highly neurotic people are more susceptible to mental illness than happy-go-lucky types; they're also worse at high-risk professions like military aviation or bomb disposal, which require coolness under pressure. On the other hand, neuroticism seems linked to creative pursuits. Studies have found, for example, that artists and other creative people score higher on tests of neuroticism than people who aren't in creative fields.

"This is something that bothered me for a long time," said Adam Perkins, a lecturer in the neurobiology of personality at King's College London. Perkins is the co-author of a new opinion piece published Aug. 27 in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences that lays out the possible links between neuroticism and creativity in the brain.

Perkins was listening to a lecture by Jonathan Smallwood, a psychologist and expert on daydreaming at the University of York in England, when Smallwood mentioned that people who report high levels of negative thoughts show lots of activation in a brain region called the medial prefrontal cortex, even when they're just resting in a brain scanner. This area, which sits behind the forehead, is involved in the appraisal of threat.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's quite a simple leap to think they've got a sort of internal threat generator in their heads," Perkins told Live Science. "They can be lying down in bed or sitting in an armchair in a perfectly neutral environment, and yet they're feeling as if they're under threat."

Self-generated thoughts

These "self-generated thoughts" can obviously make people miserable, Perkins said. In essence, people are imagining problems that don't exist. Studies show that neurotic people have sensitive amygdalae, the almond-shaped brain structures involved in processing fear and anxiety. So, neurotic people not only invent problems, but tend to become very stressed by them.

But self-generated thoughts are also linked to planning skills and the ability to delay gratification. Perkins realized that the brain's internal threat generator might have pros as well.

"Neurotic people feel sort of miserable spontaneously, and they also tend to be better at coming up with creative solutions for things," he said. Isaac Newton, for example, once wrote that he solved problems by chewing over them incessantly. "I keep the subject constantly before me," he said, "and wait till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light."

Thus, the neurotic tendency to dwell on things might be the very root of creativity and problem solving, Perkins said. [Mad Geniuses: 10 Odd Tales of Famous Scientists]

Anxiety and genius

According to Perkins and his colleagues' hypothesis, the brains of neurotic people might have a particularly persistent "default mode network," which is the circuit in the brain that becomes activated when people are doing nothing in particular. The medial prefrontal cortex is part of that system. If neurotic people have trouble turning off this thought-generating network, it might make them more prone to overthinking, dwelling and otherwise mulling over problems — real and imagined.

This can be a problem because neurotic people also have oversensitive amygdalae. The tendency to become panicked over imagined problems can make neurotic people quite miserable, Perkins said.

On the other hand, neuroticism could have benefits, he said. "If you dwell on problems for a long time, when those problems are not in front of you … it seems quite obvious that you'll be more likely to come across a solution than one of those happy-go-lucky people who live their life in the moment," Perkins noted.

It's a tantalizing notion, but no one has yet done the experimental work that would prove that the same processes cause neurotic worrying and creative genius.

And finding proof will be difficult, Perkins warned. It's difficult to measure creativity in the lab. Most tests involve giving participants an ordinary object and asking them to come up with as many uses for that object as they can. That's not really the same thing as laying out the theory of evolution or inventing the jet engine, Perkins said. (Frank Whittle, inventor of the jet engine, also suffered several nervous breakdowns during his life.)

"Really creative people are rare," Perkins said. "It just seems that a lot of them are neurotic."

One concrete step toward proving the link could be to study medial prefrontal cortex activity in people with high levels of neuroticism, Perkins said. However, it might take a neurotic genius to come up with other ways forward.

"We just hope this will give some impetus to people who are cleverer than us to come up with some good tests," Perkins said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.