In late May this year, conservation groups got word that saiga, endangered antelopes that roam the grassland of Kazakhstan, were dying in droves. Though the field workers on the ground were able to get tissue samples and have conducted many tests, it's still not clear what has caused nearly half of the saigas in Kazakhstan to die off. [Read the full story on the saiga die-off]

Ominous warning

Conservationists had already planned to study the saiga during their calving season. When they arrived to central Kazakhstan in late May 2015, they had already heard that of some saiga dying. However, in recent years there have been some small die-offs, so field workers weren't too concerned. (Photo credit: Scherbinator/Shutterstock.com)

Lightning crash

But within two days of the field workers' arrival, 60 percent of the herd they were studying had died. By four days, the entire herd — about 60,000 saigas — had died off. Workers struggled to keep up with the mass dying, quickly burying the animals that died in heaps (shown here). (Photo credit: Sergei Khomenko/FAO)

Widespread scourge

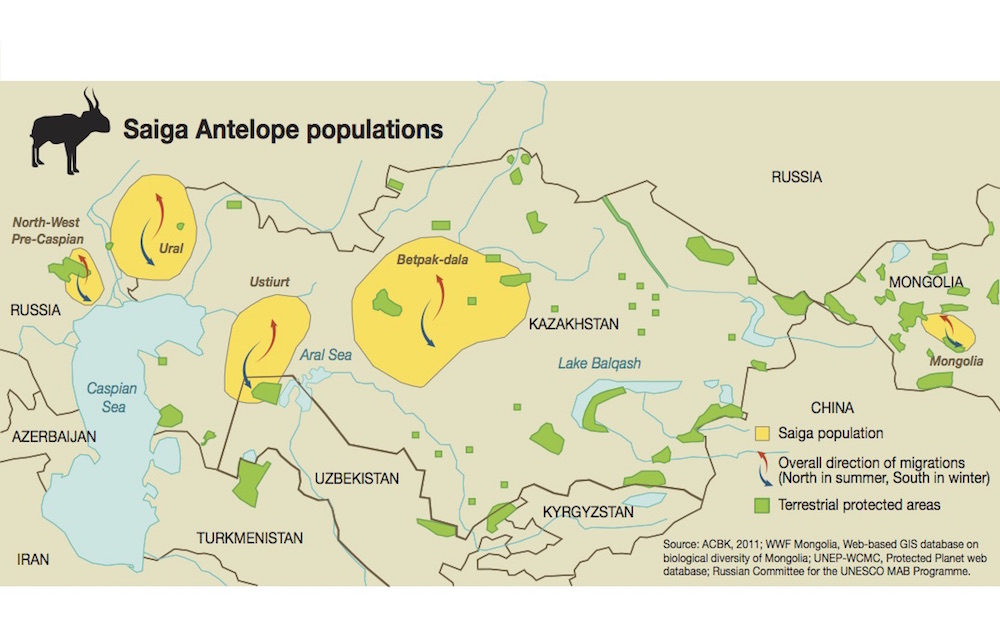

Scientists were completely baffled. When field workers from this herd, called the Betpak-dala population, contacted others in the field, they found that die-offs were occurring in other herds as well. In all, there are five saiga populations around the world — three in Kazakhstan, one in Russia and another (a different subspecies) in Mongolia. (Photo credit: ABCK, WWF, University of Mongolia, UNEP-WCMC, Russian committee for the UNESCO MAB Programme)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On the ground

Because they were already on the ground, the team was able to study the process as it unfolded. Here, several dead saiga litter the steppe. (Photo credit; Sergei Khomenko/FAO)

Mothers hit hardest

The researchers on the ground also noticed a mysterious trend: the mother saigas died off first, followed by their calves. Some calves were even seen suckling from their mothers after they had died. Because newborn calves are too young to consume anything but milk, that suggested the littlest saigas were dying because of something that was transmitted in their mothers' milk. Here, a baby calf huddles a little distance from its mother. (Photo credit: Steffen Zuther)

Tissue Samples

Because the researchers were on the ground at the time of the die-off, they were able to take detailed tissue samples from the dead animals. These necropsies revealed that bacterial toxins from a few species of pathogen had caused bleeding in all of the animals' internal organs. Here, researchers take tissue samples from a dead saiga. (Photo credit: Steffen Zuther)

Greater mystery

But that didn't resolve the mystery. The bacteria implicated — particularly one called Pasteurella — is often found in ruminants and rarely causes harm unless their immune system has already been weakened by something else. And genetic analysis suggested this was a garden-variety pathogenic form of the microbe, which has never caused such a rapid, stunning and complete crash in a population before. (Photo credit: Albert Salemgareyev/ABCK)

Quick Death

All told, more than 150,000 saiga have died so far this year. That, however, may be an underestimate, as that number only counts saiga who have been buried. If saiga wandered off into the hillsides and died alone, that death may not have been reported. Here, a field worker checks a saiga that was lying in the grass. (Photo credit: Sergei Khomenko/FAO)

Further investigation

The team also collected samples of the soil the saiga walked on, the water they drank and the vegetation they ate during the weeks and months leading up to the population crash. So far, nothing points to an obvious cause of the die-off. Other than a cold, hard winter followed by a spring with lots of lush vegetation and lots of standing water on the ground, there wasn't much unusual in the conditions this year, biologists say. Here, a herd of saiga munch on grass in the steppe. (Photo credit: Dmytro Pylypenko/Shutterstock.com)

Past die-offs

In 1988, when Kazakhstan was still part of the USSR, a similar mass die-off killed off hundreds of thousands of saiga. Researchers reported that Pasteurella was the cause then as well, but didn't do much further investigation. While researchers hope that they will identify a cause, it may be that the saiga are just very susceptible to some natural environmental condition that occurs sporadically. Here, a photo of a saiga taken in a preserve in Russia. (Photo credit: Victor Tyakht/Shutterstock.com)

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.