Disappearing Ancient Texts Could Be Saved by Solar-Powered Device

TORONTO — A 13th-century text recording the discoveries of a medieval polymath, a handwritten dictionary that may help decipher ancient texts, a magical text dating back hundreds of years and writings etched on palm leaves that record centuries of history. All of these and many more are in danger of being lost to the elements.

In this race against time, a team of engineers and archivists are developing a solar-powered device to safeguard historical treasures in India.

These documents are written on organic materials that become increasingly fragile over time. Exposure to humidity, sunlight and insects can ravage the texts, while storing them at temperatures that are too high or low can speed up the documents' decay. [In Photos: Medieval Manuscript Reveals Ghostly Faces]

What librarians, archivists and conservators try to do is preserve the most fragile texts in areas where humidity and temperature can be easily controlled, taking them out briefly to be put on display or for study. However for facilities in the developing world this can be a problem as the energy needed to power dehumidifiers and air-conditioning equipment may not be available or affordable.

The new solar-powered device that researchers are developing may help solve this problem. The machine itself is remarkably simple: Texts are placed in an insulated container with a dehumidifier and temperature-control mechanism. Solar cells power the equipment, while batteries store power when there isn't enough sunlight.

Additionally, when conditions in the container are just right, the device will automatically power down, conserving energy so that it can automatically turn on when the humidity and temperature rise.

"As long as the documents aren't accessed all day long, the power requirements aren't that hefty," said Harrison King-McBain, an engineering graduate student from the University of Toronto.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

India treasures

Colin Clarke, the director of the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents, said he became aware of the need for such a device during a trip to Kerala, India, last September. A professional librarian, Clarke had been invited to the Eighth World Syriac Conference hosted by the St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute, which is part of the Mahatma Gandhi University. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, and was used by Christians throughout Asia, as far east as China. While in Kerala, Clarke examined historical text collections in local churches and monasteries.

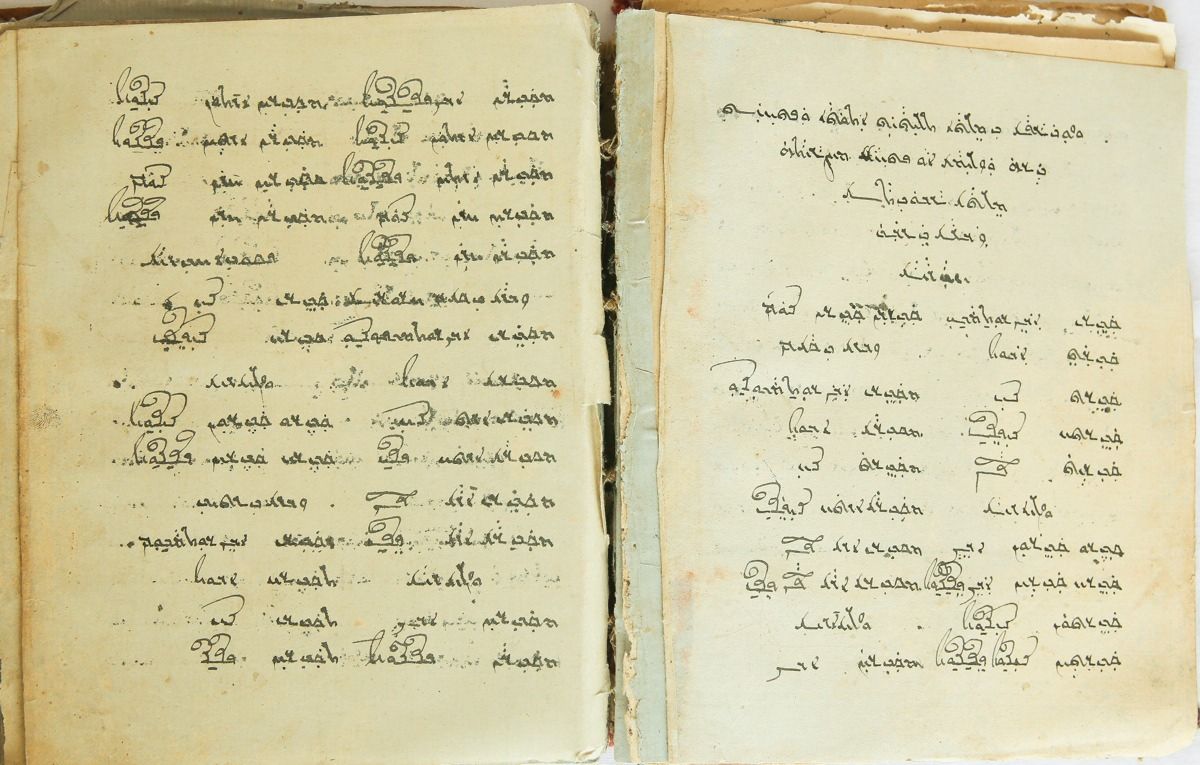

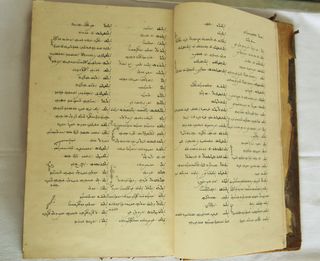

The libraries had palm-leaf documents, dating back hundreds of years and written in Malayalam, a Classical Indian language widely used in the area. There were also manuscripts written in Syriac. One text that Clarke is particularly excited about dates to the 13th century and may have been written by a man named Bar Hebraeus, a polymath who wrote about literature, science, philosophy, religion, history and medicine, Clarke said. [See Photos of 19th-Century Medical Texts]

"The 13th-century manuscript may have been written by Bar Hebraeus himself," Clarke said. "Bar Hebraeus was one of the greatest thinkers of his day. This is like having a manuscript written in Aristotle's own hand. Definitely, this would be a world treasure, if the attribution is correct."

Providing humidity and temperature control is challenging. A corepiscopa (a country bishop) in charge of a large manuscript repository told Clarke that even if the repository had the equipment, the owners would not be able to afford the energy needed to operate it.

Clarke promised to help. When he returned to Canada, he contacted King-McBain and Michael Cino, a graduate student at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. The team has constructed a "proof of concept" device that shows how the device will work, demonstrating it at the University of Toronto on Aug. 19.

The team has also found a place in Kottayam, Kerala, India, to build the solar units. Clarke said that a solar technology firm is now needed to finish development and help with construction. Clarke asks anyone who can help to contact him through the CCED website.

Help required

The solar-powered device requires no fuel and is designed so that it needs little or no maintenance, said King-McBain. The team kept the design as simple as possible, using off-the-shelf components to keep costs down. The device has no moving parts that can easily break down.

The unit will cost between roughly $3,000 and $5,000, an amount that Clarke said would be difficult for facilities in developing countries to afford. The Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents is trying to raise enough funds so that a few of these devices can be constructed and installed at facilities in India, Clarke said.

There are ways in which the device can be improved. One problem is that texts made of different materials often require different temperature and humidity levels. This means that one device may only be able to preserve texts made of one type of material.

Often a repository will have texts made of different materials that require different environmental settings. Installing two or more units with different environmental settings in these facilities is an option, but that would raise the cost, Clarke said. Another option would be for the container to have different compartments, the environment in the compartments configured to hold texts made with different materials. However, this would make the design more complex.

"The team is working against time and cost," Clarke said. "Irreplaceable texts are in danger of being lost through environmental factors. We have the solution. Now we need the support to fix this problem," Clarke said.

Follow Live Science@livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.