New Species of Ancient 'River' Dolphin Actually Lived in the Ocean

The fossilized remains of a new species of ancient river dolphin that lived at least 5.8 million years ago have been found in Panama, and the discovery could shed light on the evolutionary history of these freshwater mammals.

Researchers found half a skull, a lower jaw with an almost complete set of conical teeth, a right shoulder blade and two small bones from a flipper. The fossils are estimated to be between 5.8 million and 6.1 million years old, making them from the late Miocene epoch, researchers said in a new study.

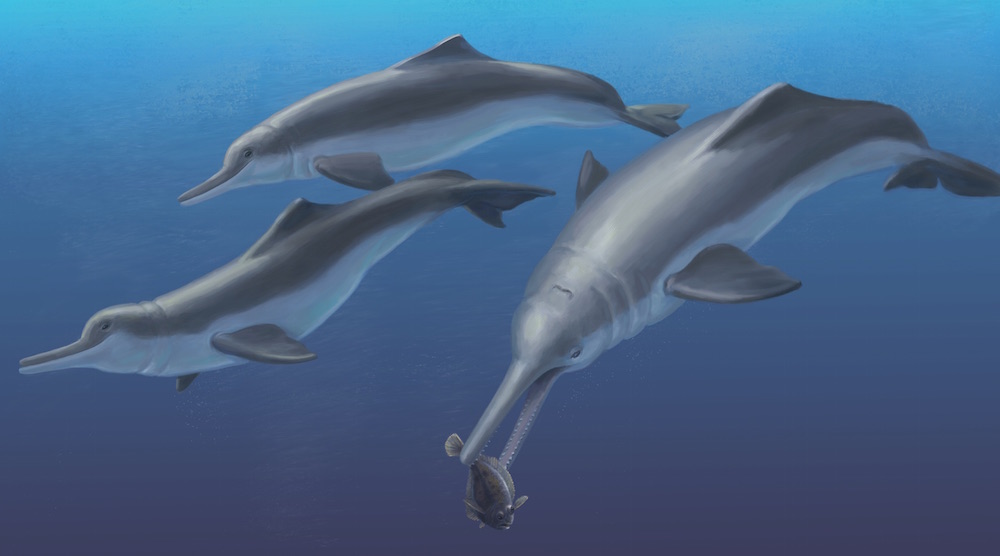

The ancient river dolphin, named Isthminia panamensis, was calculated to be more than 9 feet (2.7 meters) long, according to the study. [Deep Divers: A Gallery of Dolphins]

The ancient mammal was discovered on the Caribbean coast of Panama, at the same site where other marine animal fossils have been found, which suggests that I. panamensiswas also a saltwater species, the researchers said.

I. panamensis is the only fossil of a river dolphin known from the Caribbean, the researchers said in the study.

"We discovered this new fossil in marine rocks, and many of the features of its skull and jaws point to it having been a marine inhabitant, like modern oceanic dolphins," study lead author Nicholas Pyenson, a curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., said in a statement.

But despite dwelling in the salty waters of the Caribbean Sea, I. panamensis is actually more closely related to modern-day freshwater river dolphins, the researchers said. In fact, "Isthminia is actually the closest relative of the living Amazon river dolphin," study co-author Aaron O'Dea, a staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only four species of river dolphins exist today (although one, the Yangtze river dolphin, is now likely extinct), all living in freshwater or coastal ecosystems. All of these river dolphins moved from marine to freshwater habitats, developing broad, paddlelike flippers; flexible necks; and heads with particularly long, narrow snouts as they evolved, according to the study. These adaptations allowed the river dolphins to better navigate and hunt in winding, silty rivers, the researchers said.

"Many other iconic freshwater species in the Amazon — such as manatees, turtles and stingrays — have marine ancestors, but until now, the fossil record of river dolphins in this basin has not revealed much about their marine ancestry," Pyenson said. "[I. panamensis] now gives us a clear boundary in geologic time for understanding when this lineage invaded Amazonia."

Whales and dolphins evolved from terrestrial ancestors into marine animals, but river dolphins represent a backward evolutionary path, moving from oceans inland to freshwater ecosystems, the researchers said.

"As such, fossil specimens may tell stories not just of the evolution of these aquatic animals, but also of the changing geographies and ecosystems of the past," O'Dea said.

The study was published today (Sept. 1) in the journal PeerJ.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.