Why Record-Breaking Hurricane Trio Swirls Above the Pacific

A parade of tropical storms traipses across the Pacific in a new satellite image showing the once-in-a-lifetime (or more than one lifetime) event.

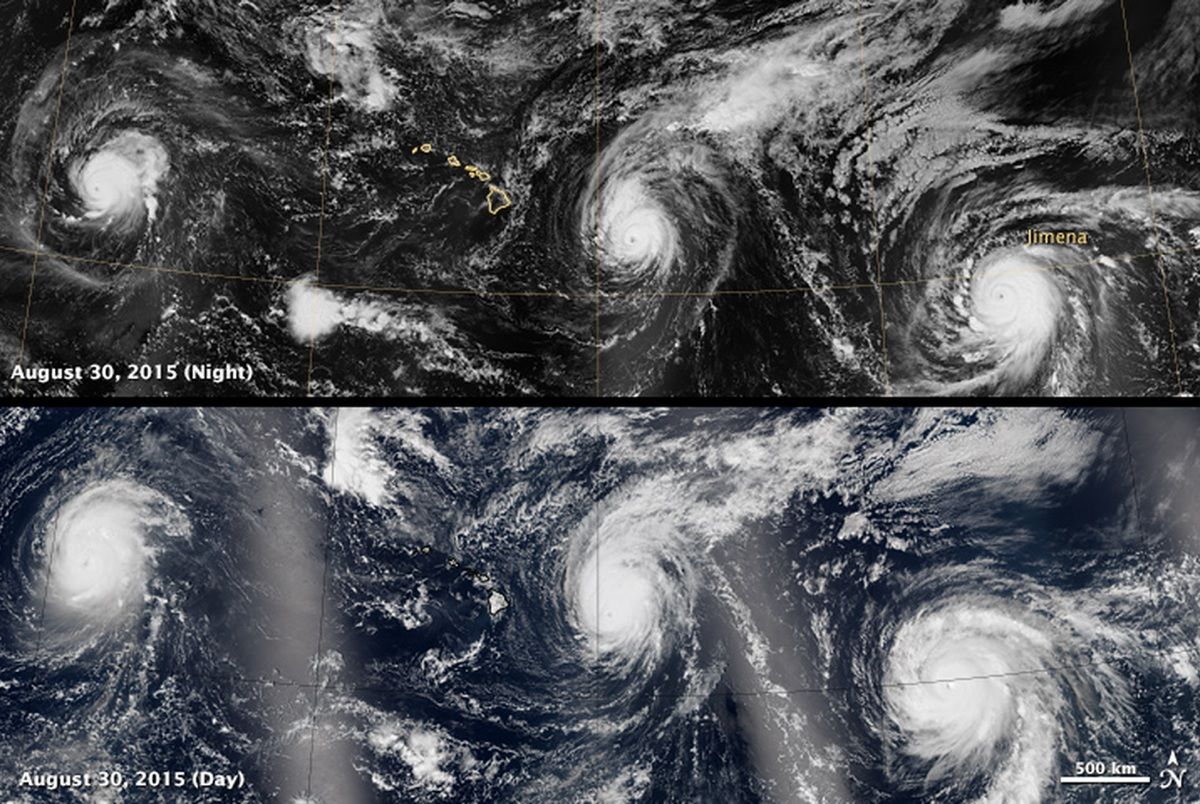

Kilo, Ignacio and Jimena were all Category 4 hurricanes when these mosaic images over Hawaii were made on Aug. 29 and 30. Category 4 storms have winds ranging from 130 to 156 mph (209 to 251 km/h) — strong enough to uproot trees and severely damage structures, according to the National Weather Service.

This is the first time three major hurricanes have lined up across the central and eastern Pacific at the same time, according to meteorologist Eric Blake of the National Hurricane Center.

It's an unusual event but one that's made more likely by the climate cycle called El Niño, said Tom Evans, the acting director of the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.

"The reason we're getting so many tropical cyclones in our area is that El Niño is keeping the very warm waters well north of the equator," Evans told Live Science. "That's one of the main contributors to the energy found in hurricanes." [Famous Examples of the 5 Hurricane Categories]

In addition, Evans said, El Niño decreases the typical flow of the trade winds, lessening wind shear (changes in wind speed, in this case over a vertical distance), which makes the atmosphere more conducive to hurricane formation.

NASA's Earth-orbiting satellite called Suomi-NPP captured daytime and nighttime images of the stormy trio using an instrument called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). The images are mosaics, stitched together from multiple passes of the satellite.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The nighttime view was taken between 11:30 p.m. on Aug. 29 and 3 a.m. on Aug. 30, Hawaii Standard Time, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Kilo is on the left, Ignacio is in the middle and Jimena is on the right. The Hawaiian Islands sit between Kilo and Ignacio. Misty diagonal areas that seem to extend downward from each hurricane are actually moon glint off the Pacific.

The daytime view was taken between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. Hawaii Standard Time on Aug. 30; the bright lines are sunlight reflecting off the ocean. Though the storms appear right on one another's tails, they are far enough away that they aren't interacting, Evans said.

At the time of these images, the National Hurricane Center reported that Jimena's maximum sustained wind speed was 130 mph (209 km/h). The storm has since moved from the eastern Pacific to the central Pacific. As of 8 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time on Tuesday (Sept. 1), Jimena had weakened slightly and had maximum sustained wind speeds of 120 mph (193 km/h).

Ignacio was whirling along with sustained wind speeds of up to 140 mph (225 km/h) at the time of these images; as of 5 a.m. Hawaii Standard Time on Sept. 1, the maximum wind speeds had dropped to 80 mph (129 km/h), according to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.

Kilo had also weakened slightly as of 5 p.m. Hawaii Standard Time on Aug. 31, when its maximum sustained wind speeds clocked in at 125 mph (201 km/h), down from 135 mph (217 km/h) when the Suomi-NPP satellite flew over.

Kilo and Jimena are not threatening land. Ignacio, however, is causing large swells on the eastern and northeastern shores of the Hawaiian Islands, according to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center. This rough surf is expected to continue for several more days.

The busy Pacific hurricane season matches with forecasts made earlier this spring. El Niño not only boosts storms in the Pacific, but suppresses them in the Atlantic, meteorologists say. That may explain the lower-than-normal hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean this season.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.