Male Seahorses Act Like Pregnant Mammals, Study Suggests

Pregnant male seahorses tend to develop embryos similarly to the way mammals do, new research shows.

In the new study, scientists found a suite of genes that are "turned on" in the pouches of seahorses to keep the baby healthy and growing. Similar gene activity has been found in the wombs of mammals and even reptiles.

As such, the finding could shed light on the evolution of live birth, called viviparity.

Seahorse broods

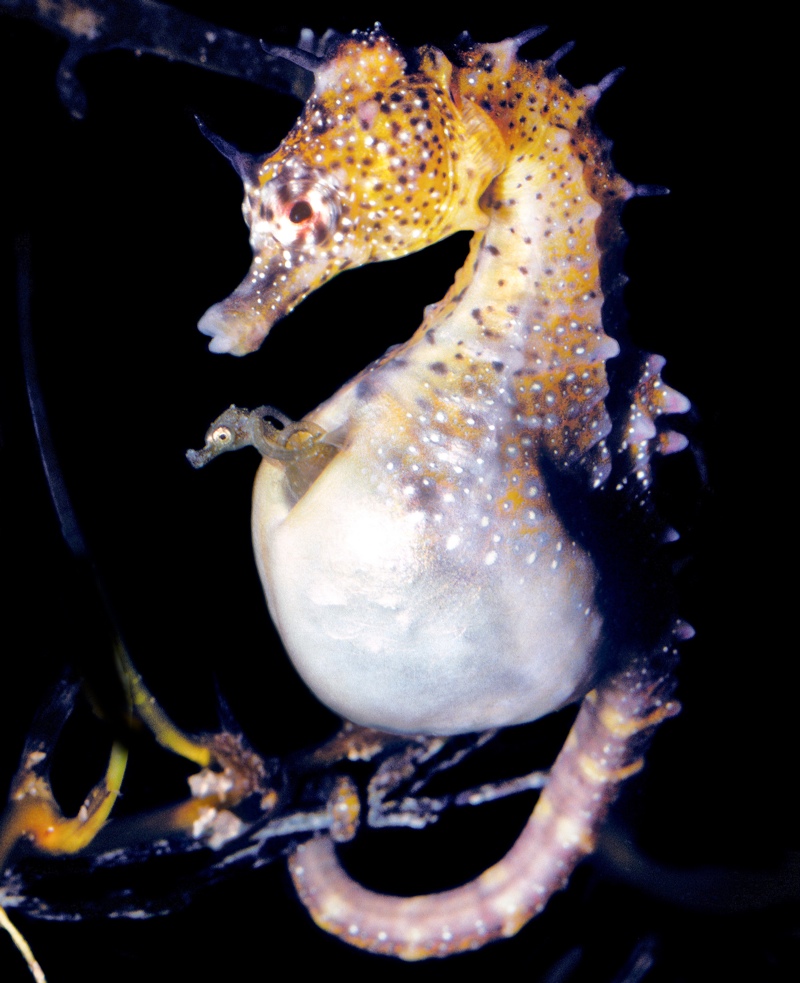

Seahorses are syngnathid fishes — the only animal family in which males, not females, carry their young. In seahorse sex, the female deposits her eggs into a "brood pouch" on the male's stomach, where he fertilizes them. The expectant dad then carries the eggs in this pouch during the 24-day gestation period until he gives birth, using abdominal contractions to expel the live young, which are then on their own to survive. [The 10 Wildest Pregnancies in the Animal Kingdom]

Previously, researchers knew little about what took place in the brood pouch of the pot-bellied seahorse (Hippocampus abdominalis) during pregnancy. To find out, an international team of researchers looked at how genes were turned on and off during the course of the expecting dads' pregnancies. They compared this activity with that found in the brood pouches of nonpregnant males. (Just as nonpregnant women have uteruses, nonpregnant male seahorses have brood pouches.)

They specifically looked at ribonucleic acid, or RNA in the seahorses' brood pouches (RNA is produced when a gene is turned on and tells the cell to build the protein that the gene encodes.) Then, they looked for similar gene sequences (and their functions) in publicly available databases.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pouches and uteruses

Pregnancy led to an uptick in the expression of genes involved in nutrient transport within the brood pouch, the scientists found. "Things like fats, and also calcium, seem to be transported from the dad [to the developing fetus]," said study author Camilla M. Whittington, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Sydney in Australia. "We also found a whole lot of other genes for things like immune function, so it looks like the seahorse dads can actually help prevent infection in the brood pouch."

The researchers also found changes in the expression of genes involved in tissue remodeling. These genes may be involved in structural changes to the brood pouch, which thickens and develops more blood vessels when carrying the brood (of several hundred embryos), Whittington said. The team found gene-expression changes associated with immune-system activities (both protecting the embryos from infection and preventing the father's immune system from rejecting the tissue of his offspring as foreign), gas exchange (so that the embryo can "breathe"), and waste removal.

The brood pouch is said to have the same function as the uterus of mammals and reptiles. Consistent with that idea, the researchers found many similarities between the genes expressed in the male seahorses' brood pouches and similar genes (called homologues) expressed in the uteruses of female mammals — rats, in particular — and the womb equivalents of reptiles and fish that have live young. Those similarities could potentiality extend to humans, Whittington said. [Infographic: For How Long Are Animals Pregnant?]

"People have looked at gene expression in the rat uterus during pregnancy, whereas we don't have a similar data set for humans," Whittington said. "Obviously, it's kind of difficult to get those kinds of tissue samples, and that's probably why people haven't done it. So we found mammalian homologues, and we presume some of them will be human homologues, too, but we don't have the data to be able to tell."

Bearing live young

Research of this sort may reveal details about how viviparity evolved, Whittington said. The trait is thought to have evolved independently 150 times in vertebrates, including 23 times in fishes, the authors wrote in the study.

Once animals "stop laying eggs and start having live babies instead, animals are faced with a common set of challenges," Whittington said. "Somehow, wastes have to be removed from the embryo, somehow oxygen has to be delivered and somehow nutrients have to be delivered.

"There are perhaps a limited number of genetic ways that this could be done, and so this is why we're seeing the same genes being recruited into pregnancy in these animals," Whittington added.

This process of turning on certain genes during pregnancy could be an example of convergent evolution, in which evolutionarily separated species develop similar ways of doing things by evolving under similar environmental conditions.

"These animals have evolved pregnancy millions of years apart and also in completely different structures," Whittington added. This supports the convergent evolution idea. "Mammals use a uterus, whereas the seahorses are using, essentially, modified abdominal skin," Whittington said.

Alternatively, viviparous animals around today could have had a common ancestor in which these genes were already turned on in the tissues that later evolved to become the uterus and the brood pouch.

"I think our research shows that we are more like other animals than you might think," Whittington added. "I think it really illustrates that there are commonalities in pregnancies across really diverse vertebrates, and I think that's really exciting."

The research was published online Sept. 1 in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Follow Ashley P. Taylor @crenshawseeds. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Ashley P. Taylor is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York. As a science writer, she focuses on molecular biology and health, though she enjoys learning about experiments of all kinds. Ashley's work has appeared in Live Science, The New York Times blogs, The Scientist, Yale Medicine and PopularMechanics.com. Ashley studied biology at Oberlin College, worked in several labs and earned a master's degree in science journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.