Early Humans Climbed Down from Trees Gradually

The last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees may have had shoulders that were similar to those of modern African apes, researchers say. The finding supports the notion that the human lineage shifted to a life away from trees gradually.

The human lineage diverged from that of chimpanzees, humanity's closest living relative, about 6 million or 7 million years ago. Knowing the characteristics of the last common ancestor of humans and chimps would shed light on how the anatomy and behavior of both lineages evolved over time, "but fossils from that time are rare," said lead author of the new study Nathan Young, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

There are currently at least two competing scenarios for what the last common ancestor might have looked like. One suggests that similarities seen in modern African apes, such as in chimps and gorillas, were inherited from the last common ancestor, meaning that modern African apes may reflect what the last common ancestor was like. [See Images of Our Closest Human Ancestor]

"A lot of people use chimpanzees as a model for the last common ancestor," Young told Live Science.

The other scenario suggests these similarities instead evolved independently in modern African apes, and that the last common ancestor may have possessed more-primitive traits than those seen in modern African apes. For instance, instead of knuckle-walking on the ground like chimps and gorillas do, the last common ancestor may have swung and hung from tree branches like orangutans, which are Asian apes.

"Humans aren't the only species that have evolved and changed over time — chimpanzees and gorillas have evolved and changed over time, too, so looking at their modern forms for insights into what the last common ancestor was like could be misleading in a lot of ways," Young said.

The ancestral state of the shoulder is key to understanding human evolution, because the shoulder is linked to many important shifts in behavior in the human lineage. Shoulder evolution could help show when early human ancestors began using tools more, spent reduced time in trees and learned to throw weapons. However, the human shoulder possesses a unique combination of features that makes it difficult to reconstruct the body part's history. For instance, while humans are most closely related to knuckle-walking chimps, in some respects the human shoulder is more similar in shape to that of tree-dwelling orangutans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

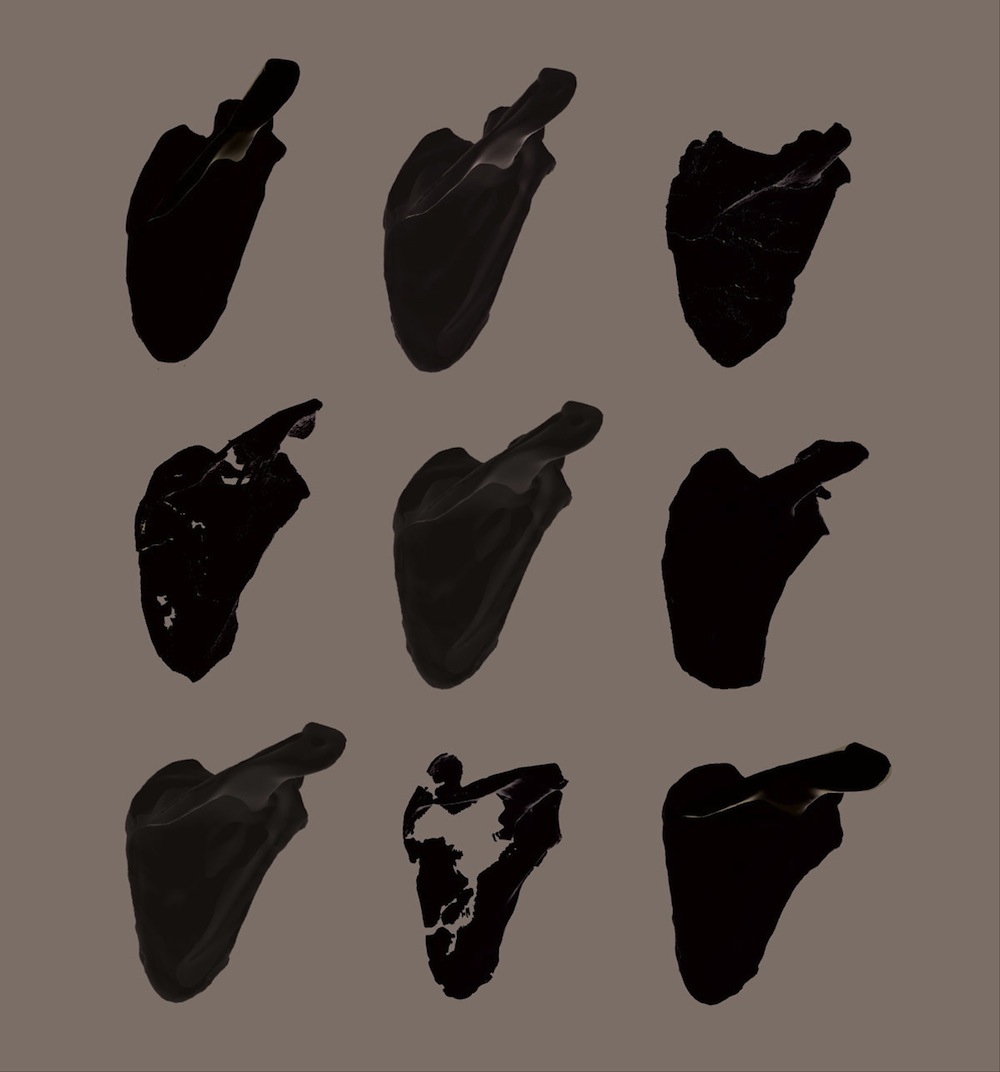

To see what the shoulder of the last common ancestor might have looked like, researchers generated 3D shoulder models from museum specimens of modern humans, chimps, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, gibbons and monkeys. The scientists compared these data with 3D models that other scientists previously generated of ancient, extinct relatives of modern humans, such as Australopithecus afarensis, Australopithecus sediba, Homo ergaster and Neanderthals. Australopithecines such as Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus sediba are the leading candidates for direct ancestors of humans.

"Recent data from the australopithecines helped us now test different models of human evolution," Young said.

The scientists found the strongest model showed the human shoulder gradually evolving from an African apelike form to its modern state.

"We found australopithecines were perfect intermediate forms between African apes and modern humans," Young said.

This finding suggests the human lineage experienced a long, gradual shift out of the trees and increased reliance on tools as it became more terrestrial, he said.

"These results pretty much confirm that the simplest explanation for how the human shoulder evolved is the most likely one," Young said.

In the future, Young and his colleagues would like to see how variations in shoulder shape make people better or worse at activities such as throwing or lifting, or more prone to rotator cuff injuries or arthritis, the researchers said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 7 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality