Deadly Parasite Could Be Zapped Like a Cancer Cell

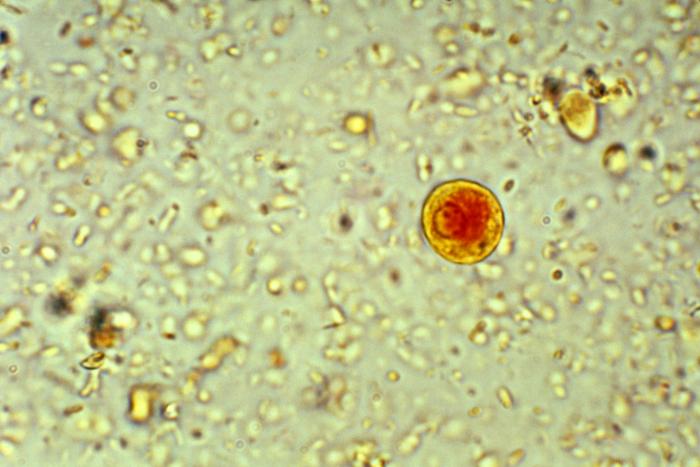

The ameba Entamoeba histolytica is among the deadliest parasites in the world, infecting more than 50 million people and killing upward of 100,000 annually, according to the World Health Organization.

The ameba's scientific name means "tissue destroyer," and refers to its ability to bore through a person's intestines and into the liver and other organs, causing ulcers, internal bleeding and chronic diarrhea. (Ameba is an alternate spelling of "amoeba," and can be used with organisms that do not belong to the genus Amoeba, as E. histolytica.)

Doctors have only one antibiotic that can treat people with E. histolytica infections, and they fear the parasite will soon develop resistance to it. And when that happens, "there's no plan B," said Dr. William Petri, an expert on parasitic infections and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases & International Health at the University of Virginia.

But a chance meeting between Petri and a bladder cancer expert, Dr. Dan Theodorescu, who is director of the University of Colorado Cancer Center, has now resulted in a novel approach to finding the parasite's Achilles' heel.

In short, the two scientists were trying to use E. histolytica to kill cancer cells. Normally, in his research on chemotherapy drugs, Theodorescu used a technique called RNAi, which silences various genes, in order to understand which genes make a drug less or more effective in killing the cancer. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

Petri merely substituted E. histolytica for a drug.

The scientists found, to their surprise, that silencing the genes that normally let potassium flow out of the cell could keep the cells alive. Drugs that do the same thing might be used to slow the damage caused by E. histolytica, the scientists said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This could be the plan B — targeting the human genes that enable the parasite to cause disease," said Petri, adding that this was the first time such an RNAi approach was used on an ameba, and that this could have a broad impact on the field of infectious diseases.

The finding was published today (Sept. 8) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Humans can become infected with E. histolytica by ingesting food or water contaminated with its cysts. The ameba passes into the environment via feces and can survive outside the human body for several weeks in this protective cyst form.

E. histolytica infection is endemic in regions with poor sanitation, and improving sanitation has been the primary means to stop infections, said Chelsea Marie, a postdoctoral fellow in Petri's lab and first author on the report. The sole antibiotic that is effective in killing E. histolytica is metronidazole, which many patients find hard to tolerate, because of its side effects.

Targeting the potassium-ion channels in the colon, the first organ affected by E. histolytica, represents an entirely new approach in thwarting E. histolytica infection, Marie said.

In the lab, Marie reversed the experiment and found that using chemicals to block potassium efflux made the cells resistant to E. histolytica. Nevertheless, challenges lie ahead in developing medicine for use in humans, she said.

"The challenge with developing drugs that target ion channels" such as potassium channels is that these channels are found all over the body, and are critical for many cellular processes, Marie told Live Science. "We are currently working on identifying the specific channels that are unique to the colon and could be specifically targeted to prevent cell death during [ameba infection]," she said.

"This approach also could be informative for colon cancer chemotherapy, because activating the same specific colonic potassium channels might kill cancer cells," Marie said.

As with many great scientific discoveries, this one came about through luck and happenstance, the scientists joked. Theodorescu and Petri have known each other socially for years but have never collaborated or even talked about their research. "What's an ameba have to do with cancer, after all?" Theodorescu said. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

But recently the two were working together, on a hiring committee, and wound up killing time for an hour while waiting for a job interviewee to arrive. They made small talk to pass the time, and eventually Petri told Theodorescu about a complicated experiment he was about to start to identify toxins released by E. histolytica and ways to block them. Theodorescu suggested that Petri take a genetic approach, to see which genes, when blocked, would make cells resistant to the infection. He had the cells ready to go. So Petri gave it a shot.

"It was pure luck that I ended up on this paper," Theodorescu said. "This was serendipity at its best."

In 2012, other scientists discovered that the rheumatoid arthritis drug auranofin was as effective as metronidazole in killing E. histolytica in laboratory samples. Preliminary tests were begun on healthy volunteers in 2014; no results have yet been reported.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.