Key to Survival Found for Sailors Shipwrecked in Alaska in 1813

In 1813, the Russian-American Company frigate Neva wrecked near Kruzof Island, Alaska. The survivors managed to live for nearly a month — in winter — despite struggling to shore with almost nothing.

Now, archaeologists are uncovering the story of how these sailors lived until rescuers arrived. The researchers found that the sailors started fires with gunflints and steel scraps and cannibalized the ship's wreckage to build the tools they used to survive.

"The items left behind by survivors provide a unique snapshot-in-time for January 1813, and might help us to understand the adaptations that allowed them to await rescue in a frigid, unfamiliar environment," Dave McMahan, an archaeologist and member of the Sitka Historical Society, who is excavating the site of the Neva survivors' camp near the city of Sitka, said in a statement. [See Photos of Amazing Shipwrecks from Around the World]

Lost cause

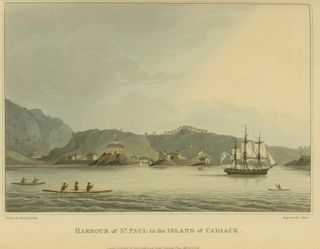

The Neva was carrying about 75 people and a shipment of goods that included guns and furs when it left Okhotsk, Russia, in August of 1812. According to the National Science Foundation, which is funding the new excavations, the sailors endured three months of storms, sickness and water shortages before arriving in Alaska's Prince William Sound.

Though storms had damaged the ship's rigging, the crew pushed eastward toward Sitka, just south of what is now Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Near Kruzof Island, mere miles from their destination, the ship hit rock and went down. Twenty-eight members of the original crew made it to shore (15 had already died at sea before the wreck). Of those survivors, only two died before rescuers arrived nearly a month later.

With the help of the oral history of the indigenous Tlingit people, McMahan and his colleagues located the site of the survivor camp near the shore where the Neva went down. The researchers found hearths surrounded by artifacts: copper, musket balls and a Russian axe. The researchers realized that, in many cases, they were looking at washed-up wreckage that the sailors desperately modified to make something useful. For example, musket balls had been whittled down to fit smaller weapons than the ones they were made for. A fishhook was fashioned out of copper scraps.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Collectively, the artifacts reflect improvisation in a survival situation," McMahan said.

No graves were found, in part because the archaeologists avoided disturbing too much of the site, which is in an area significant to the Tlingit people.

Ongoing discovery

Before it foundered in Alaskan waters, the Neva was an important ship; it was part of the armada that helped defeat the Tlingit in 1804, enabling the Russians to establish the city that would become Sitka.

Researchers have been excavating at the Neva survivors' camp for two years, and plan another season of fieldwork in the upcoming year.

Archaeologists are surveying the ocean floor for signs of the shipwreck, but thick kelp forests are hampering those efforts. The researchers are also searching for historical records of the shipwreck and rescue efforts; few written records have been discovered. Anyone with information related to the wreck — even just family lore — should contact the Sitka Historical Society, McMahan said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular