NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has begun beaming home the best data from its epic July Pluto flyby.

On July 14, New Horizons became the first probe ever to fly by Pluto, zooming within 7,800 miles (12,550 kilometers) of the dwarf planet's enigmatic surface. New Horizons sent some images and measurements back to its handlers immediately after the encounter, but stored the vast majority onboard for later transmission.

That transmission — which involves tens of gigabits of information — began in earnest on Saturday (Sept. 5) and should take about a year to complete, mission team members said. [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

"This is what we came for — these images, spectra and other data types that are going to help us understand the origin and the evolution of the Pluto system for the first time," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement.

"And what’s coming is not just the remaining 95 percent of the data that’s still aboard the spacecraft — it’s the best data sets, the highest-resolution images and spectra, the most important atmospheric data sets and more," Stern added. "It’s a treasure trove."

New Horizons is beaming its data back with the help of NASA's Deep Space Network, a system of big radio dishes in California, Spain and Australia that serves a variety of agency spacecraft.

The typical downlink rate is between 1 and 4 kilobits per second, NASA officials said. And communication is far from instantaneous; New Horizons is about 3 billion miles (4.8 billion kilometers) from Earth, so it takes signals from the craft, which are traveling at the speed of light, about 4.5 hours to get here.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

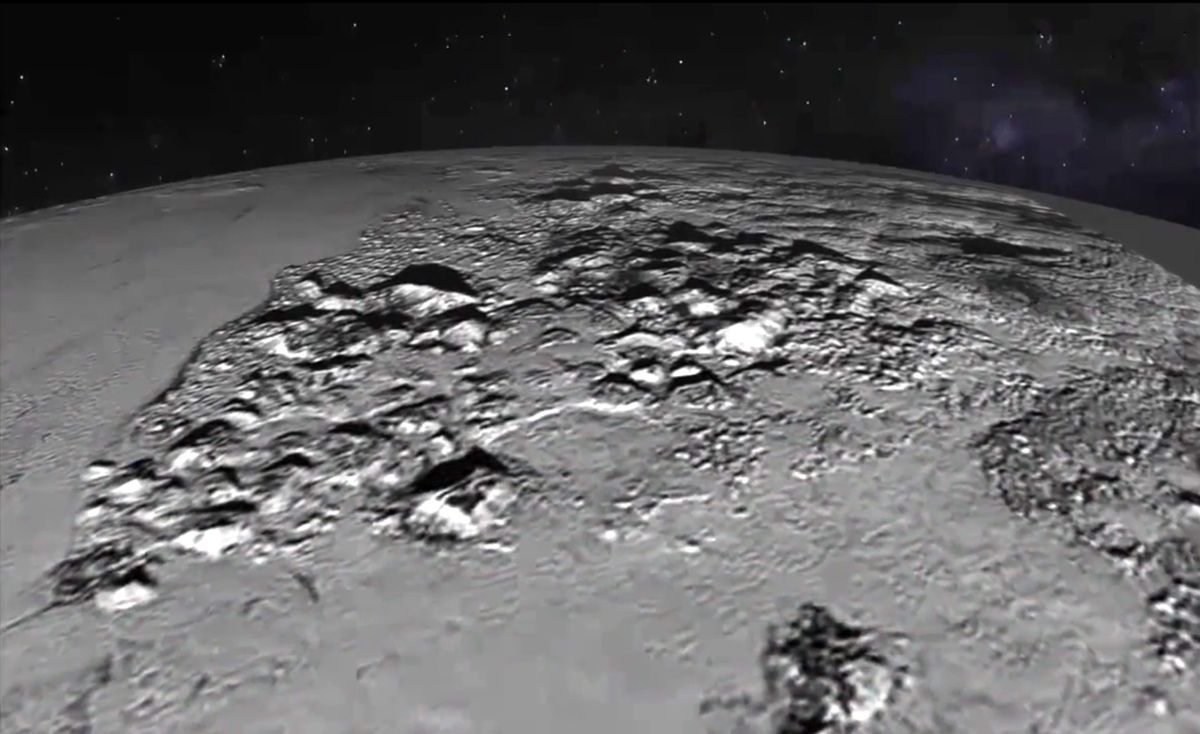

The images that New Horizons has already beamed home revealed towering ice mountains and vast, geologically young plains on Pluto, as well as giant canyons on the dwarf planet's largest moon, Charon. Mission team members therefore have high hopes about the probe's complete flyby data set.

"The New Horizons mission has required patience for many years, but from the small amount of data we saw around the Pluto flyby, we know the results to come will be well worth the wait," said New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, of the the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

New Horizons is probably not done gathering data. The probe's handlers will soon begin steering it toward a small object called 2014 MU69, which lies about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto. If NASA approves a proposed extended mission for New Horizons, the spacecraft will fly by 2014 MU69 in early 2019.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.