An Ocean Flows Under Saturn's Icy Moon Enceladus

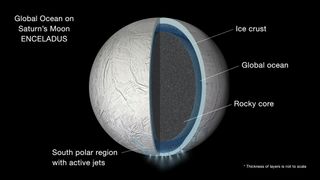

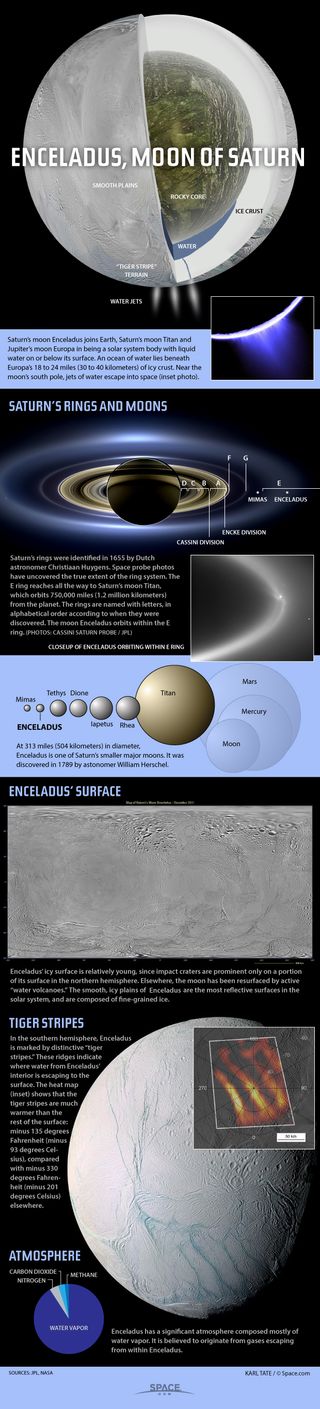

Saturn's moon Enceladus is an active water world with a global body of water sloshing around deep below its icy crust, scientists have confirmed.

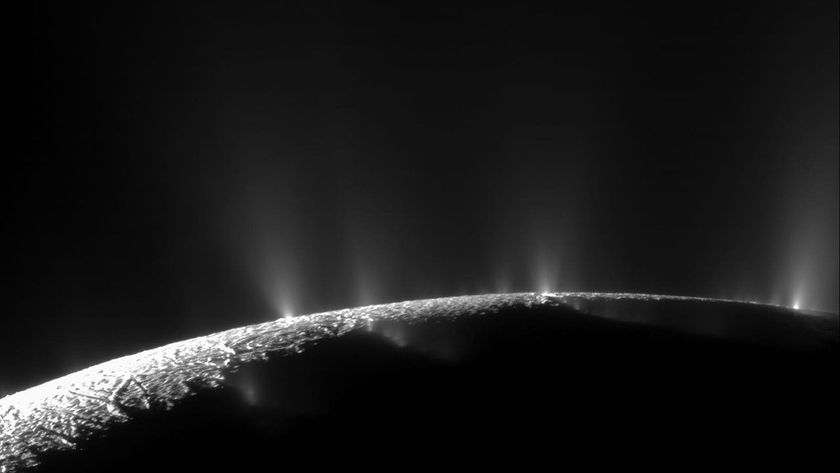

Gorgeous geysers of water have been observed erupting from Enceladus' surface, providing direct evidence of a reservoir of the life-giving liquid below the surface. But scientists were unsure if the satellite contained an entire ocean, or just a small body of water concentrated at its south pole.

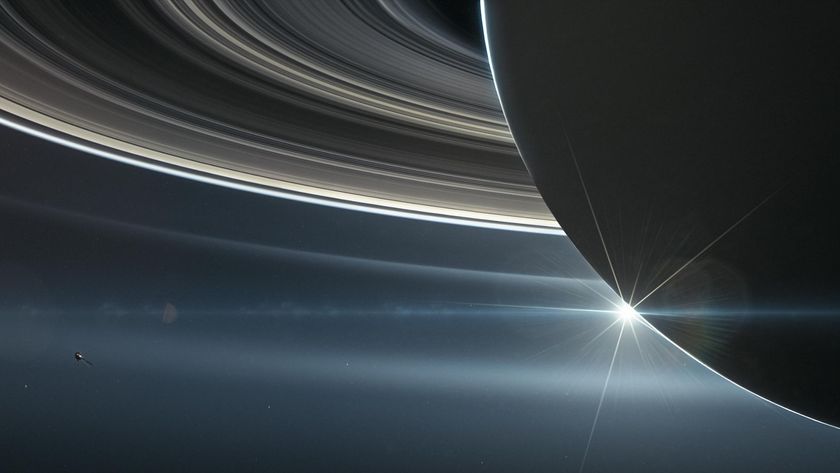

The smoking gun is the very slight wobble that Enceladus displays as it orbits Saturn. This unsteady motion is effectively the result of water sloshing around inside Enceladus, and could not appear if the moon were made of ice all the way to its core. Instead, the moon must contain a complete ocean layer, according to new research that relied on more than seven years of images taken by NASA's Cassini space probe. [Photos of Enceladus, Saturn's Icy Moon]

"This was a hard problem that required years of observations, and calculations involving a diverse collection of disciplines, but we are confident we finally got it right," Peter Thomas, lead author of the new work and a Cassini imaging team member at Cornell University, said in a statementfrom the Cassini imaging team.

Thomas and his colleagues studied images of Enceladus to precisely measure changes in its rotation, then ran several simulations to determine how the interior of the moon would affect those wobbles.

Wobbly wet moon

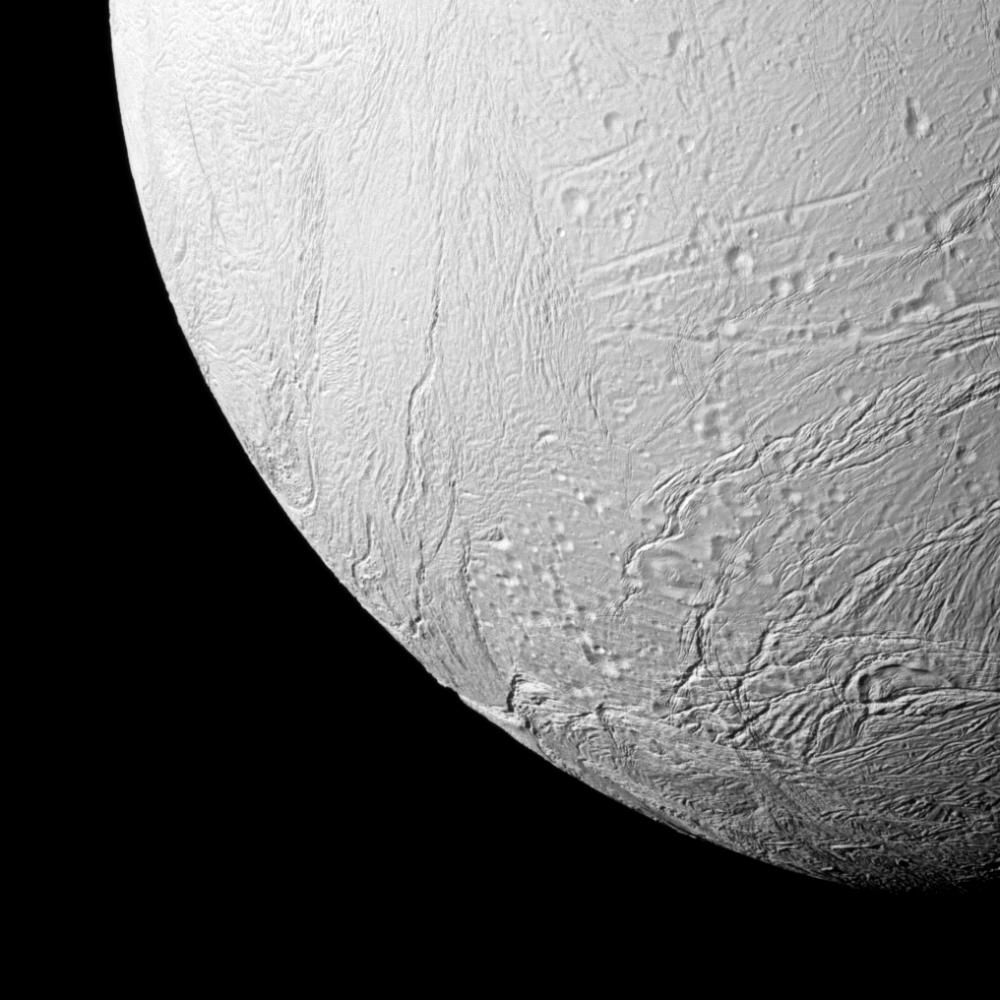

Not long after NASA's Cassini mission arrived at Saturn, it detected signs of icy plumes spurting from the southern hemisphere. Further observation suggested that the fractures at the south pole, dubbed "tiger stripes," were the source of the geysers, allowing material from the interior to leak into space.

Originally, scientists thought only a small local sea existed beneath the icy crust, supplying the plumes with material. Gravitational mapping of the world collected during Cassini's close passes suggested that the sea might be global, but could not be confirmed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Following an independent line of research, Thomas and his team analyzed more than seven years of images of Enceladus, carefully mapping features on the moon across hundreds of images to measure changes in its rotation. They found that the tiny world has a small but measurable wobble as it orbits the ringed giant Saturn.

The team then ran several simulations to determine how the wobble would affect the moon if it had a variety of interiors, including one that was completely frozen. They found that the wobble was explained only if Enceladus contained a global ocean beneath its icy crust.

"If the surface and core were rigidly connected, the core would provide so much dead weight the wobble would be far smaller than we observe it to be," co-author Matthew Tiscareno, a Cassini participating scientist at the SETI Institute in California, said in the same statement.

"This proves that there must be a global layer of liquid separating the surface from the core."

The mystery of Enceladus' ocean

How Enceladus could have maintained a liquid ocean for so long remains a mystery. Thomas and his colleagues suggested ideas for a future study that might help resolve the question, including the idea that tidal forces produced by the gravity of Saturn could generate more heat within the moon than previously anticipated.

"This is a major step beyond what we understood about this moon before, and it demonstrates the kind of deep-dive discoveries we can make with long-lived orbiter missions to other planets," said co-author Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at the Space Science Institute in Colorado. Currently, NASA scientists are considering sending a spacecraft to Enceladus as early as 2021.

"Cassini has been exemplary in this regard," Porco said.

The research was published online in the journal Icarus.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.