Yesterday (Sept. 23), Pope Francis canonized Junipero Serra, the man who first brought Catholicism to California. The move has sparked controversy because Serra was tied to a system that decimated the population of Native Americans.

But Junipero Serra is far from the most controversial saint out there. Though many people see the saints as a group of supernaturally perfect goody-two-shoes unstained by even the slightest bad deed, the true communion of saints is a motley bunch.

"The saints were not perfect. They're exactly like us," said Thomas Craughwell, the author of "Saints Behaving Badly: The Cutthroats, Crooks, Trollops, Con Men and Devil-Worshippers Who Became Saints" (Image, 2006). "They committed sins. They had bad habits. They did stupid stuff." [The 10 Most Controversial Miracles]

What ultimately gained these individuals entrance to sainthood, Catholic theology says, was not a spotless life but rather a singular focus on getting closer to God, Craughwell said.

From riffraff to fanatics who would probably classify for multiple psychiatric diagnoses, to those whose stories are too good to be true, here are some of the wickedest, strangest and most controversial saints around.

Playboys and seductresses

One of the most illustrious saints of the Catholic Church, the fourth-century scholar Augustine of Hippo, is well-known for saying, "God, grant me chastity and continence, but not yet."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The wealthy Augustine was a playboy of sorts, having not one, but two mistresses. He ran around for years before having a change of heart at age 31. After that, he ditched his mistresses to become engaged, though he ended up breaking off that commitment as well. He instead spent the rest of his life celibate, while teaching and spreading the Christian message.

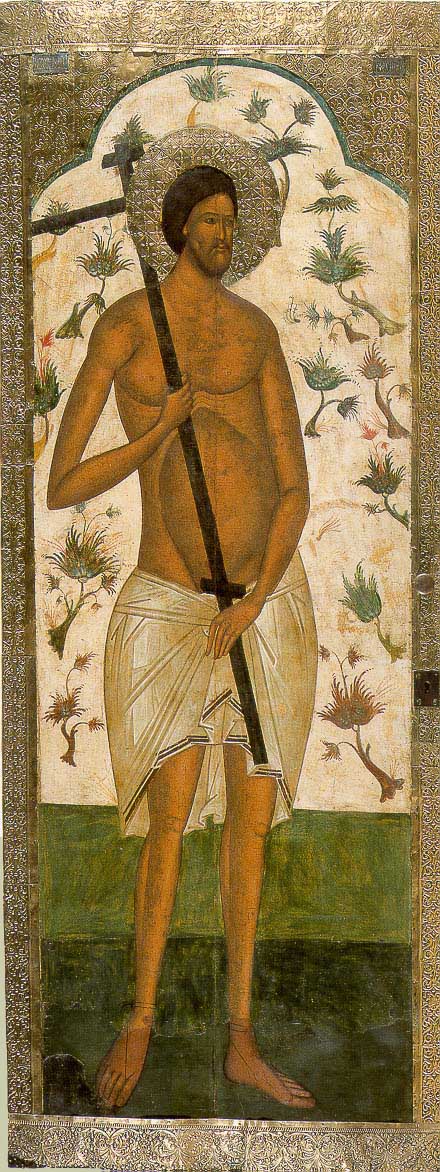

But Augustine's escapades are no match for Saint Mary of Egypt, who also lived during the fourth century. According to lore, the young girl ran away from home at age 12 and spent more than a dozen years living on the street as a seductress.

"Nothing made her happier than corrupting innocent young Christian men," Craughwell told Live Science. "She once joined a pilgrimage to Rome and seduced not only the entire crew on the ship, but she seduced all the pilgrims as well."

After years of exuberant sinning, Saint Mary of Egypt changed her ways. She had gone to Jerusalem looking for young Christians to seduce at church. But when she reached the doors of a church, she felt a strange force repulsing her, and immediately felt the wickedness of her life, repented, prayed to the Virgin Mary and took communion. After hearing a voice tell her to cross the Jordan River, she spent 47 years living in isolation in the desert, surviving mostly off herbs, according to the accounts of a sixth-century patriarch, Saint Sophronius.

Mary and Augustine aren't alone. The communion of the saints includes Saint Callixtus, who was an embezzler before turning his life around and becoming the bishop of Rome in 218, Craughwell said. Saint Camillus de Lellis, a 15th-century Italian priest who founded one of the first health care organizations for the needy, started out as a cardsharp, con man and mercenary, Craughwell said. [Papal Primary: History's Most Intriguing Popes]

"He was not somebody you would want to hang out with," Craughwell said.

Repentance just under the wire

Some saints spend years cultivating virtue and holiness so that they can be assured entrance to heaven. But a few saints are the ultimate procrastinators, sneaking in repentance just under the wire.

The most famous of these last-minute penitence-seekers is Saint Dismas, the thief who supposedly died on the cross alongside Jesus. Legend has it that Saint Dismas repented only minutes before his death, gaining him entrance to heaven.

In more recent times, Jacques Fesch, a French playboy, bank robber and murderer, had a fervent change of heart while in prison awaiting the guillotine in 1957. The dissolute and wicked man had fathered two children and abandoned both, then planned a bank heist when his parents refused to foot the bill for a yacht to sail to Tahiti. He shot and killed a police officer in his escape from the heist, and his complete lack of contrition (and general obnoxiousness) spurred the judge to sentence Fresch to death.

Even in prison, he spent his first months utterly unapologetic, until he had a powerful conversion experience and began to repent his actions, Craughwell said. When he was guillotined, his last words were "Holy Mother Mary, have mercy on me," Craughwell said.

Though Fesch hasn't been officially canonized, a French Cardinal did recommend the man for sainthood, Craughwell said.

Fanatic devotion

The third century was a strange time for Christian devotion in the Middle East, particularly Egypt, Craughwell said. Monks would spend decades in the desert, where they lived off leaves and herbs, and slept on boards or inside tombs. [Religious Mysteries: 8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

"They were incredibly extreme in their penances," Craughwell said. "It was just unhealthy, possibly even psychotic."

For instance, Saint Simeon Stylites was one of the most famous pillar-hermits — he lived on top of a pillar for years. (Yes, there were multiple pillar-hermits.) The former shepherd boy, who was born in 338 near modern-day Syria, became a monk at 16. He focused on such outlandish and extreme penances that his brethren thought him ill-suited to live in the community, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia.

He allegedly fasted from all food or water for the 40 days of Lent, and then upped the ante by doing so while standing upright as long as possible. When news of his extreme devotion spread, pilgrims came to him in the desert seeking advice. To avoid this nuisance and better focus on his prayers, he had a small pillar built and stayed atop it for decades, conversing with people only if they climbed a small ladder perched near his pillar. Over the years, the pillar grew from 9 feet (2.7 meters) to 50 feet (12.7 m) in height, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Many of the most revered and honored saints, such as Teresa of Avila, also spent years depriving themselves of food and water. For instance, Teresa would use twigs and olive branches to make herself vomit — which nowadays would be classified as bulimia, according a 2001 study in the Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture.

On days when she took communion, Saint Catherine of Siena would go to her study and vomit up any food that she ate, according to the study. In fact, according to the book "Holy Anorexia" (University of Chicago Press, 1954), fully half of the medieval saints showed symptoms of anorexia.

Imaginary friends

Some of the most controversial saints are those who didn't exist. In the early days of the church, popular cults of devotion would spring up around people based on rumor, folklore and hearsay. Some of those people's lives were holy, but others, not so much.

And some didn't exist at all.

For instance, Saint Barbara was allegedly a wealthy fourth-century woman who was persecuted by her father for her Christian faith. Along the way to becoming a martyred saint, legend has it her betrayers were transformed into stone statues and locusts, her wounds were miraculously healed and her father was struck dead by lightning.

The only problem?

"Saint Barbara's story is fantastic, but there's just no evidence. She probably never existed," Craughwell said.

When the church did some housekeeping in 1969, it removed Saint Barbara's feast day from the calendar, Craughwell said.

In addition, during the Middle Ages, rumor mills and hatemongers spread the lie that Jews had murdered little boys and used their blood for Jewish rituals, a phenomenon known as the blood libel. The public used these lies as an excuse to terrorize Jewish communities, and then held these little boys up as martyred saints. The church never officially canonized these "saints," however, and now actively discourages their veneration, Craughwell said.

Stricter rules

Though many dubious saints were raised up to exalted status by popular claim and rumor, they were essentially grandfathered into their positions. Nowadays, it's much tougher to make it onto the holy dream team.

After a priest who "got shanked in a barroom brawl" in the 10th century gained popular support as a saint in Scandinavia, the church decided to take control of the process, Craughwell said.

After that, only individual bishops could approve candidates for sainthood. Nowadays, every detail of a potential saint's life is scrutinized, and candidates for sainthood must be credited with two documented miracles to earn the official title.

"What's at the heart of it is that [Catholic officials] don't want to make a mistake. They don't want to put 'S, T, period' in front of somebody who doesn't deserve the title," Craughwell said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.