New maps of Ceres show the dwarf planet's mysterious bright spots and huge, pyramid-shaped mountain in a new light.

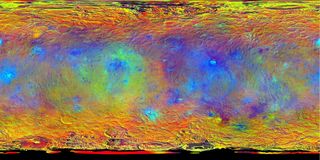

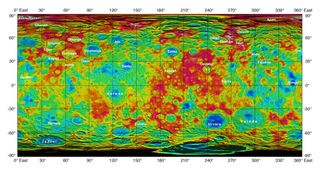

The new maps of Ceres come courtesy of NASA's Dawn spacecraft, which has been orbiting the heavily cratered dwarf planet since March. The maps highlight the compositional and elevation differences across Ceres, the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

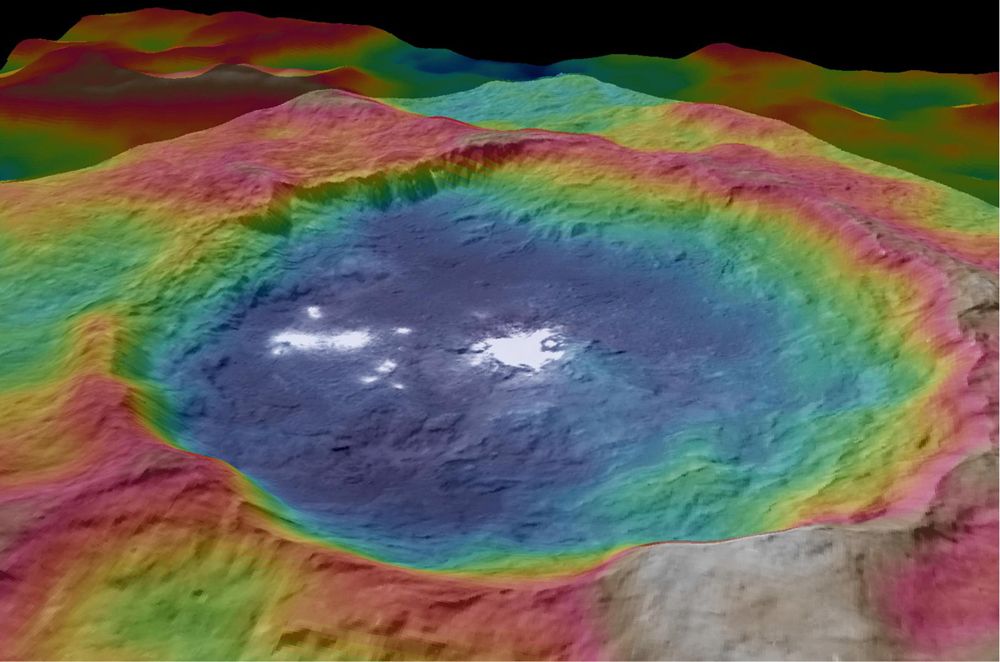

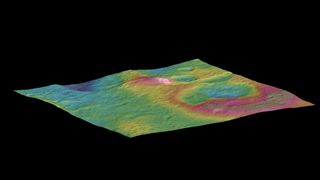

For example, one new topographic map focuses on an odd mountain dubbed "the Pyramid," which rises about 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) into space from Ceres' surface. And another map zeroes in on the 56-mile-wide (90 km) Occator crater, whose floor features the most luminescent of the dwarf planet's enigmatic bright spots. [Ceres' Mysterious Bright Spots Coming Into Focus (Video)]

The mission team also put together global Ceres composition and topographic maps, the latter of which includes names for some features on the dwarf planet that were recently approved by the International Astronomical Union.

These names all have an agricultural theme. For instance, a 12-mile-wide (20 km) mountain near Ceres' north pole now bears the appellation Ysolo Mons, after a festival in Albania marking the first day of the eggplant harvest, NASA officials said.

The new Ceres maps are being discussed at the European Planetary Science Conference (EPSC) in Nantes, France, which runs from Sept. 27 through Oct. 2. At EPSC, Dawn team members are also talking about a puzzling observation made by the spacecraft — three bursts of energetic electrons from Ceres that may have been produced by interactions between the dwarf planet and solar radiation, NASA officials said.

"This is a very unexpected observation for which we are now testing hypotheses," Dawn principal investigator Chris Russell, of the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. "Ceres continues to amaze, yet puzzle us as we examine our multitude of images, spectra and now energetic particle bursts."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dawn is currently studying Ceres from an altitude of 915 miles (1,470 km). But next month, the probe will begin spiraling down to a closer orbit, which will bring it within just 230 miles (375 km) of the dwarf planet's surface.

Dawn is expected to reach that orbit in December. (Dawn employs ion engines, which are superefficient but feature very low thrust levels, so it takes the spacecraft a while to maneuver to new positions.) The probe will remain in this mapping orbit through the end of its mission, in mid-2016.

The $466 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007 to study Vesta and Ceres, the asteroid belt's two biggest denizens. Ceres is about 590 miles (950 km) wide, while Vesta's diameter is 330 miles (530 km).

Dawn orbited Vesta from July 2011 to September 2012, when it departed for Ceres. The spacecraft is the first probe ever to orbit a dwarf planet, and the first to circle two objects beyond the Earth-moon system.

The mission has uncovered many differences between Vesta and Ceres, which are both planetary building blocks left over from the solar system's early days.

"The irregular shapes of craters on Ceres are especially interesting, resembling craters we see on Saturn's icy moon Rhea," Dawn deputy principal investigator Carol Raymond, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the same statement. "They are very different from the bowl-shaped craters on Vesta."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.