3 Pioneers Win Nobel Prize in Medicine for Parasite-Fighting Drugs

The 2015 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine has been awarded to a trio of scientists for discoveries that led to new treatments for some of the most devastating parasitic diseases, the Nobel Foundation announced this morning (Oct. 5).

Half of the Nobel Prize was awarded jointly to William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura for discovering a new treatment for infections caused by roundworm parasites. The other half went to Youyou Tu for discovering a drug to fight malaria, the mosquito-transmitted disease that takes some 450,000 lives each year globally, according to the Nobel Foundation.

"These two discoveries have provided humankind with powerful new means to combat these debilitating diseases that affect hundreds of millions of people annually. The consequences in terms of improved human health and reduced suffering are immeasurable," representatives from the Nobel Foundation said in a statement. [7 Revolutionary Nobel Prizes in Medicine]

Campbell and Ōmura discovered the drug avermectin, whose derivatives have helped to treat river blindness and lymphatic filariasis. River blindness causes inflammation of the cornea and eventual blindness, and lymphatic filariasis causes chronic swelling and can lead to elephantiasis (extreme swelling of the arms and legs) and scrotal hydrocele (swelling of the scrotum).

Ōmura, a microbiologist and professor emeritus at Kitasato University in Japan, took the first step toward the discovery of the Nobel Prize-winning drug. He knew that many bacterial species in the genus Streptomyces showed antibacterial properties. Ōmura was able to isolate new Streptomyces strains from the soil and successfully culture them in the lab. From those, Ōmura chose about 50 of the most promising strains for further testing.

Then, Campbell, currently a research fellow emeritus at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey, showed that a component in one of those cultures was effective at fighting parasites in domestic and farm animals. That component was purified into the drug avermectin, which was then modified into the compound Ivermectin. The drug Ivermectin was later found to effectively kill parasitic larvae.

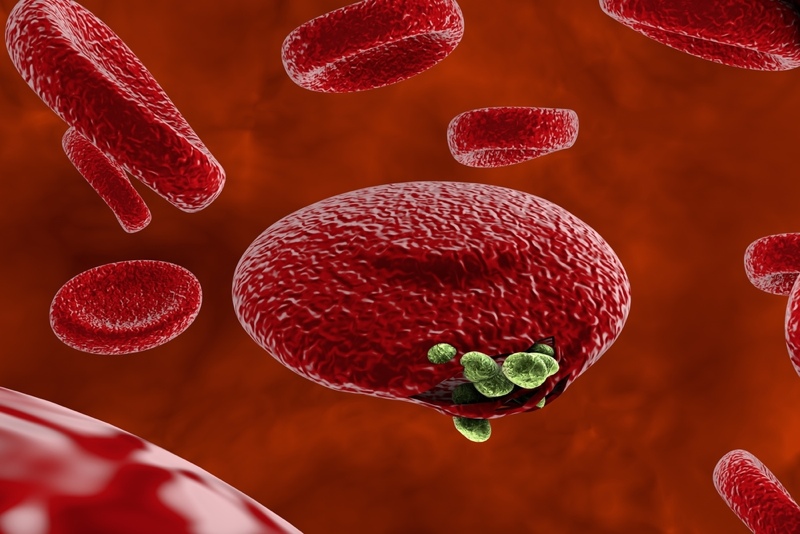

Tu's search for antimalarial agents began in the late 1960s, at a time when the disease was on the rise; traditional methods for treating malaria — chloroquine and quinine — were becoming less effective. Tu, chief professor at the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, turned to herbal medicine, and began screening such herbs in malaria-infected animals. She found one particular extract from the plant Artemisia annua that seemed promising.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After extracting the active component from the plant, Tu showed that it was effective against the malaria parasite in animals and humans. That compound is now called artemisinin.

Campbell and Ōmura will share half of this year's Nobel Prize amount of 8 million Swedish krona (about $960,000), and Tu will receive the other half of the money.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

What are mRNA vaccines, and how do they work?

Deadly motor-neuron disease treated in the womb in world 1st