Scientists at NASA have recently developed a method for visualizing the fine structure of shock waves around supersonic jets. The new technique is a digital update on a 150-year-old photography technique known as schlieren photography. [Read the whole story on the new method of visualizing shock waves]

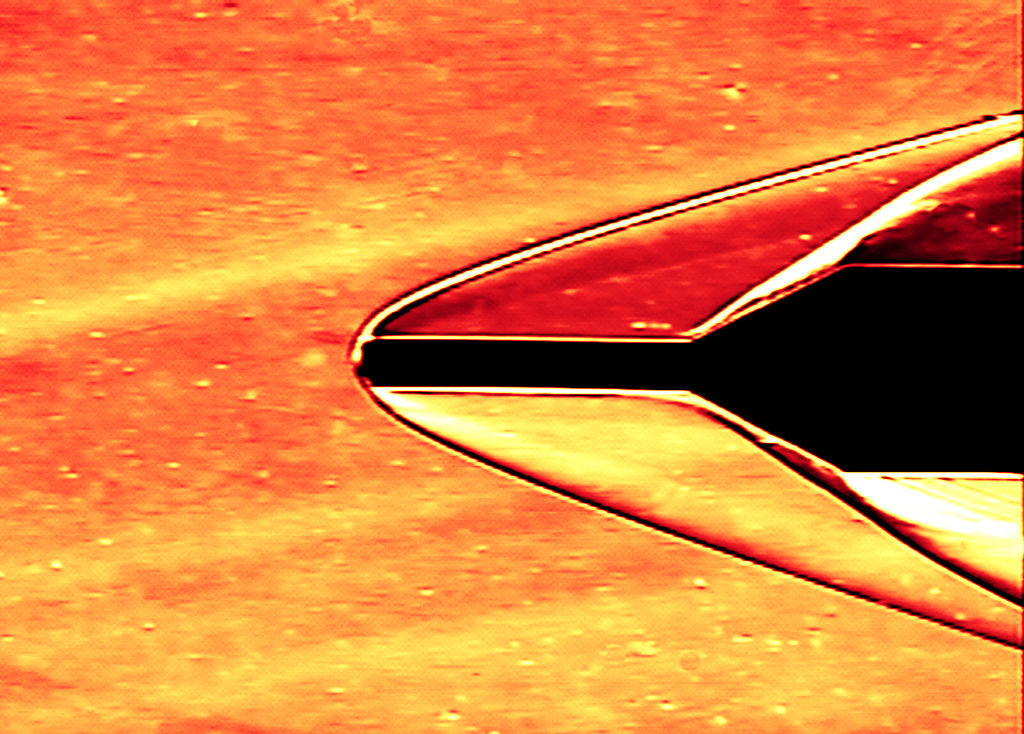

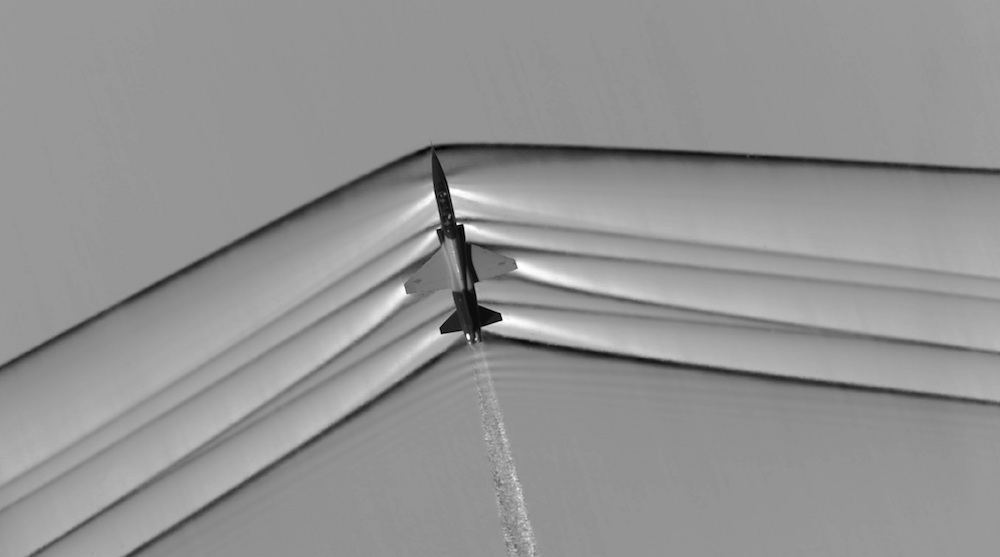

Old technique

Schlieren photography shines a light on an object in a flowing airfield, such as an airplane. When air moves around the plane, it squishes air molecules apart and pushes some together, creating an air density gradient that in turn changes how light bends around objects. These changes in the light's diffraction can then be captured on shadow images. But historically schlieren images of planes were done on in wind tunnels because of the limitations of the techniques. Here, a schlieren image of a pitot tube in a wind tunnel experience Mach 4 speeds. (Photo credit: Settles 1, Wikimedia Commons)

New approach

Some scientists figured out how to use celestial light sources such as the sun or the moon to take schlieren images of supersonic jets like this T-38 C. (Photo credit: NASA)

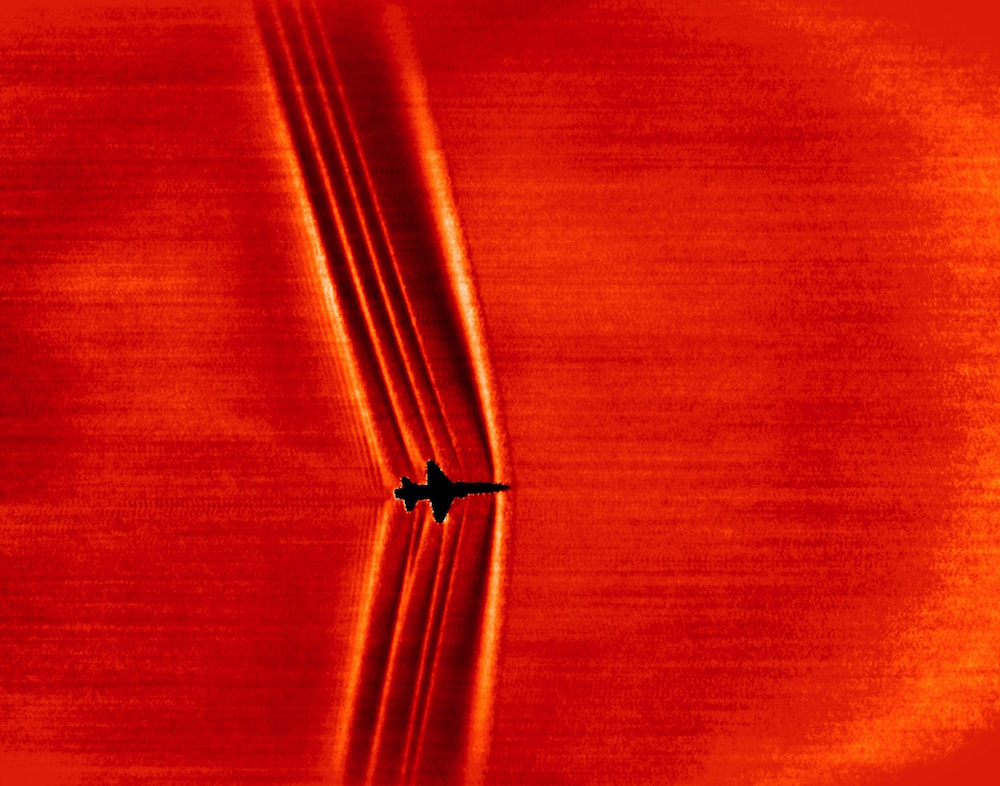

Passing the sun

Here, another image of the supersonic T-38 C as it passes by the solar disk. To get the striking purple image of the sun, the scientists photographed the speedy jet using a calcium-K optical filter, which allows photographers to capture tiny anomalies in the light near the sun. The images were captured by a ground-based system that took photographs in a narrow, two-minute window when the sun was in just the right location to eclipse the sun relative to the imaging system. (Photo credit: NASA)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

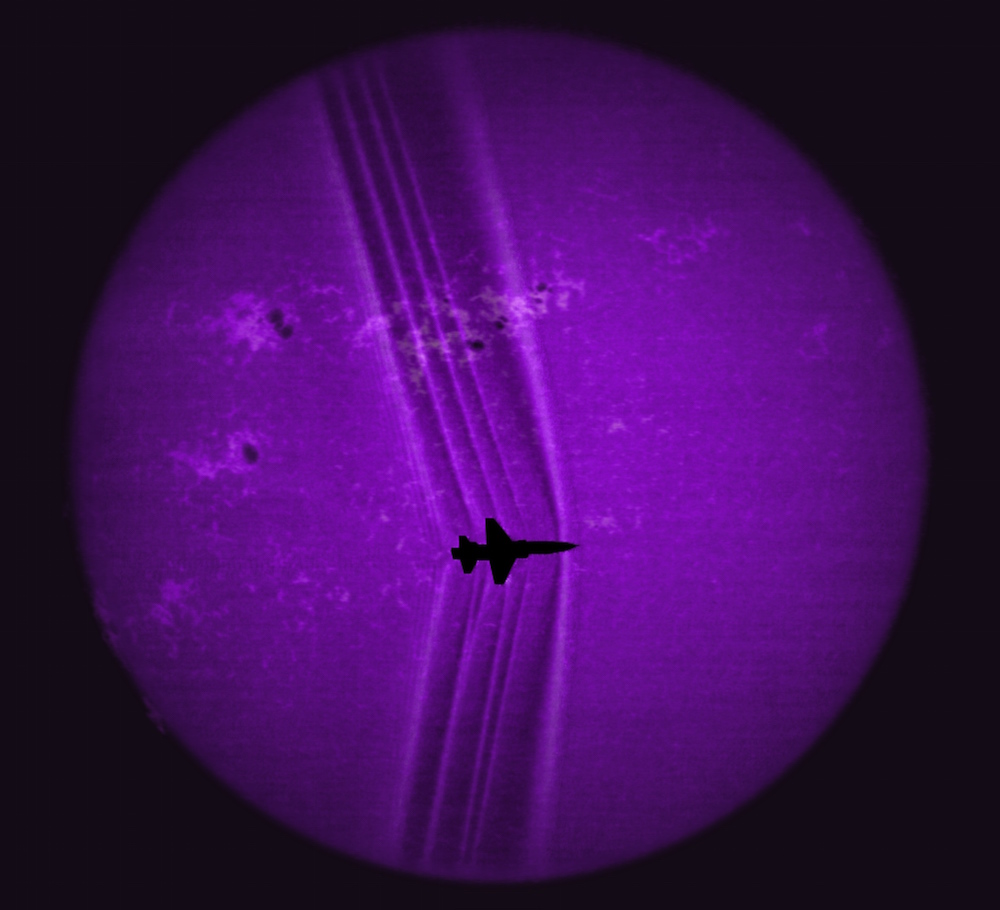

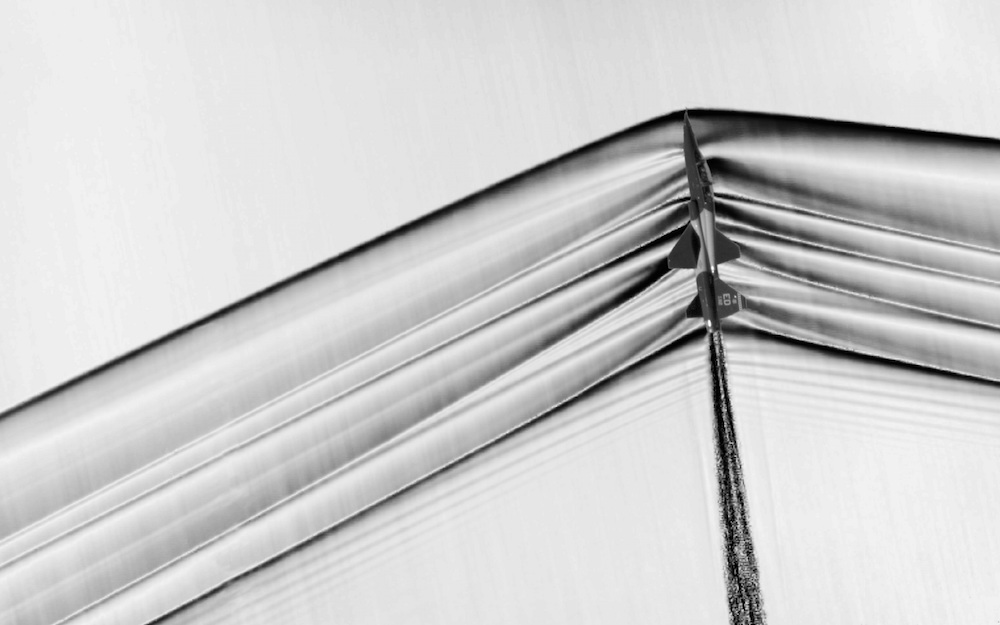

At the sun's edge

Here, the supersonic jet was captured using the sun's edge as a light source and then processed by using the naturally patterned desert scrub landscape as a background. While these images were a breakthrough and a huge advance over typical wind tunnel studies, they still weren't fine-grained enough to reveal some of the shock wave structure. (Photo credit: NASA)

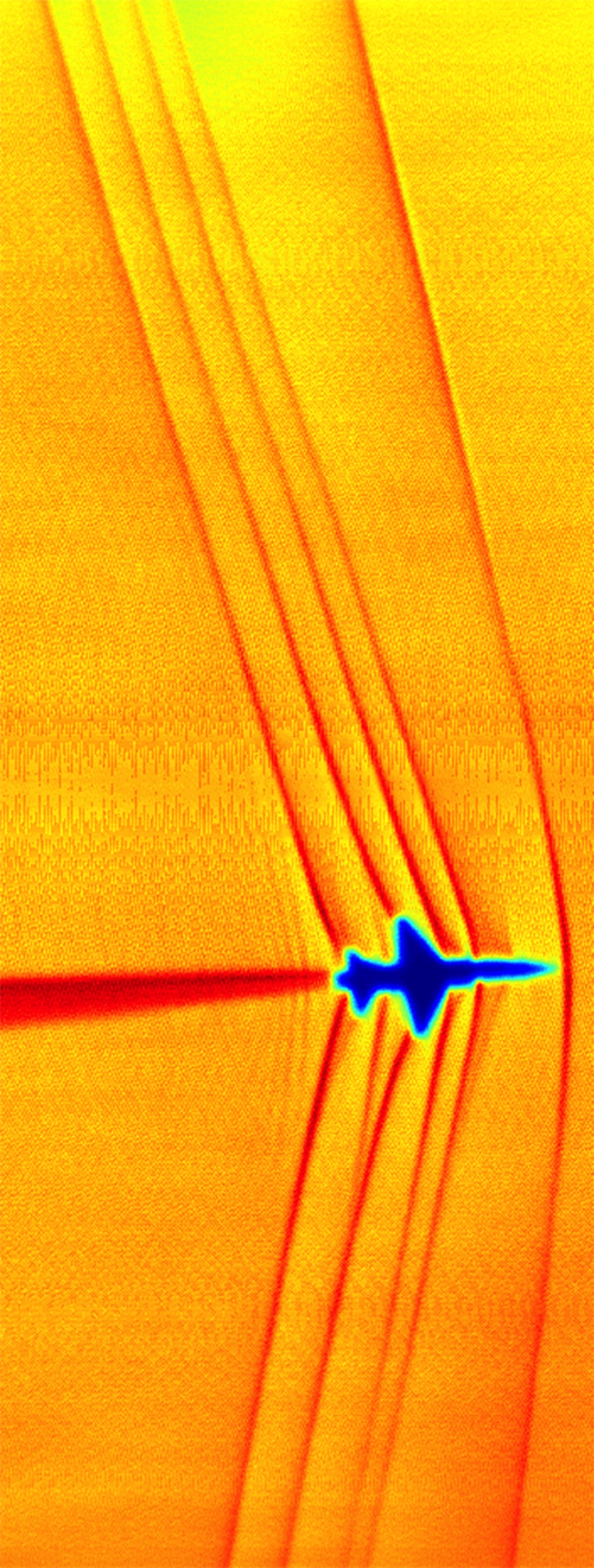

Flying high

To get better images, the team used a different method, wherein cameras mounted to a high-flying subsonic airplane captured multiple images of the supersonic plane below it. To visualize the air gradient differences caused by the shock wave, the team removed the patterned desert vegetation in the background and then averaged multiple images. The sharp pictures reveal the fine detail in the shock wave structure. (Photo credit: NASA)

Speedy plane

Here, an image of the T-38C plane from the Air Force Test Pilot School, which served as the target for the supersonic shock wave images. (Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force)

Better resolution

The new images could help scientists design better supersonic jets. While supersonic jets are normally quite noisy, the new understanding of the shock waves could help scientists design supersonic planes that were quiet enough for general civilian use. (Photo credit: NASA)

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.