Supersleuth: Virtual Assistant 'Sherlock' Uses Crowdsourced Knowledge

A new Siri-type virtual assistant promises to be as useful as the problem-solving detective Sherlock Holmes (but it’s still small enough to fit in your pocket).

Developed by researchers at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom and IBM in the United States, the new software program expands on the question-and-answer approach taken by Siri, the virtual assistant that comes with Apple's iPhones and tablets, as well as Cortana, the digital intelligence systemdeveloped by Microsoft.

Instead of just searching the Internet (or other databases) for answers to users' questions, the new virtual-assistant software gathers scraps of information from various users, stores this information in a database and then eventually puts all the scraps together to answer queries. It's similar to how a detective collects clues to crack a case. The pocket-size sleuth is aptly named SHERLOCK, short for the Simple Human Experiment Regarding Locally Observed Collective Knowledge. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

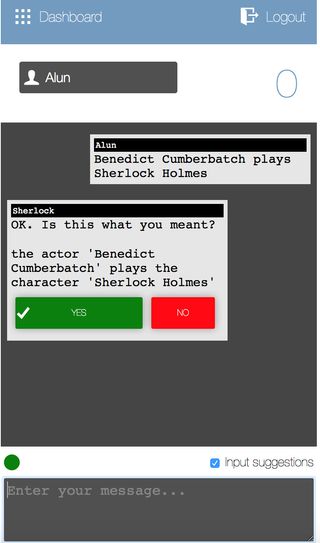

To get the information it needs, SHERLOCK uses "controlled natural language," a novel kind of machine-human language that makes communication between the software program and the user easier, according to the researchers who created the dialect.

"By using controlled natural language, SHERLOCK builds a knowledge base of things it ‘knows’ in a form that’s understandable to humans and machines," said Alun Preece, a professor of intelligent systems at Cardiff University's School of Computer Science & Informatics. "You can ask it what it knows about, and tell it about things it doesn’t know about in natural language."

The controlled language makes it easier to fill in gaps in the software's knowledge, Preece told Live Science in an email. For example, if SHERLOCK keeps giving you driving directions to a location that you usually travel to by train, you can correct its behavior by saying, "I always take the train, SHERLOCK." Or, if your house is too cold (and you happen to have a smart thermostat), you don’t have to tell SHERLOCK to turn up the heat. All you have to say is, "I'm cold, SHERLOCK."

But the software program is actually more useful as a sort of coordinator of information than as a personal assistant. By combining information from multiple users, SHERLOCK creates a local database of facts that are then available to other people using the software. The software could really come in handy in places where large crowds are gathering — for instance, at music festivals or designated emergency evacuation sites.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It can also ask people questions, like 'How big is the crowd at your location?' and then work out where are the smallest crowds from the responses," Preece said.

And because the program stores much of the information it gathers from users locally, on the users' cell phones, you don’t have to be connected to a wireless network to use the software, he added. That makes SHERLOCK really useful in situations in which networks might be down (such as during a storm) or jammed up and slow (such as during huge public gatherings).

The controlled natural language used by SHERLOCK is just one way to make communication between machines and humans easier. Earlier this year, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) unveiled Siri-like softwarethat helps humans make more informed decisions by asking them questions about their priorities. For example, the software can calculate the best route to take to the airport depending on whether you're in a hurry or you would like to first stop at a five-star restaurant for dinner.

This year, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the experimental arm of the U.S. military, also launched its Communicating with Computers(CwC) program, which aims to break down human-machine language barriers. In February, the agency unveiled a program that promotes the development of new communication methods that could be useful in fields like robotics and medical research.

Other researchers, including those at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, are bypassing language altogether by developing interfaces that let humans control technologies using only brainwaves.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.