Chilling Photos Show Coral Bleaching Across the Globe

Corals are dying across the planet. The culprit? Ever-increasing temperatures are stressing out corals' colorful partners called zooxanthellae. The result? Bleached-white corals. Now, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have found the stressful conditions are expanding from Hawaii into the Caribbean. Because of the breadth and severity of the bleaching, NOAA scientists have declared a "global coral bleaching event," only the third such declaration on record. Here's a look at what's happening beneath the world's seas.

Before and after

This before-and-after image shows the corals in American Samoa, in the South Pacific Ocean, before (image taken in December 2014) and after the bleaching event (image taken in February 2015). Corals get their rainbow hues from the microscopic algae called zooxanthellae that live in their tissues and photosynthesize to produce food for the corals. In return, the algae have a snug place to live … that is unless conditions in the water become inhospitable and they die off. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Seeing white

Alice Lawrence, a marine biologist, assesses the bleaching at Airport Reef in American Samoa in February 2015. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Coral graveyard

A researcher with the XL Catlin Seaview Survey photographs a severely bleached coral in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, in October 2014. The photos will be uploaded into Google Street View. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hawaii event

During the first mass-bleaching event in the main islands of Hawaii, a researcher with the XL Catlin Seaview Survey assesses the level of bleaching in October 2014.

Stark staghorn

Bleached staghorn coral seen in this close-up image taken in February 2015 in American Samoa. Scientists think there are hundreds of species of the branching stony coral called staghorn; these reef builders take various colors and shapes "from flat platelike colonies to pillowlike clumps to the branching, antlerlike form," according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Fire's out

A scientist records a bleached fire coral in Bermuda. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Orange and white

A fire coral in Bermuda: The one on the left is a healthy fire coral, while the one on the right is completely bleached. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Transparent skeleton

The white skeleton of a coral that lost its colorful zooxanthellae during a bleaching event in American Samoa. Like other reef-building corals, this one is not a single organism but rather a colony of hundreds to hundreds of thousands of tiny animals called polyps. Each teensy polyp has a stomach that opens at one end (the mouth), which is encircled with tentacles. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Worst 'outbreak'

A completely bleached coral photographed by the XL Catlin Seaview Survey in Hawaii during the main islands' first mass-bleaching event in late 2014. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

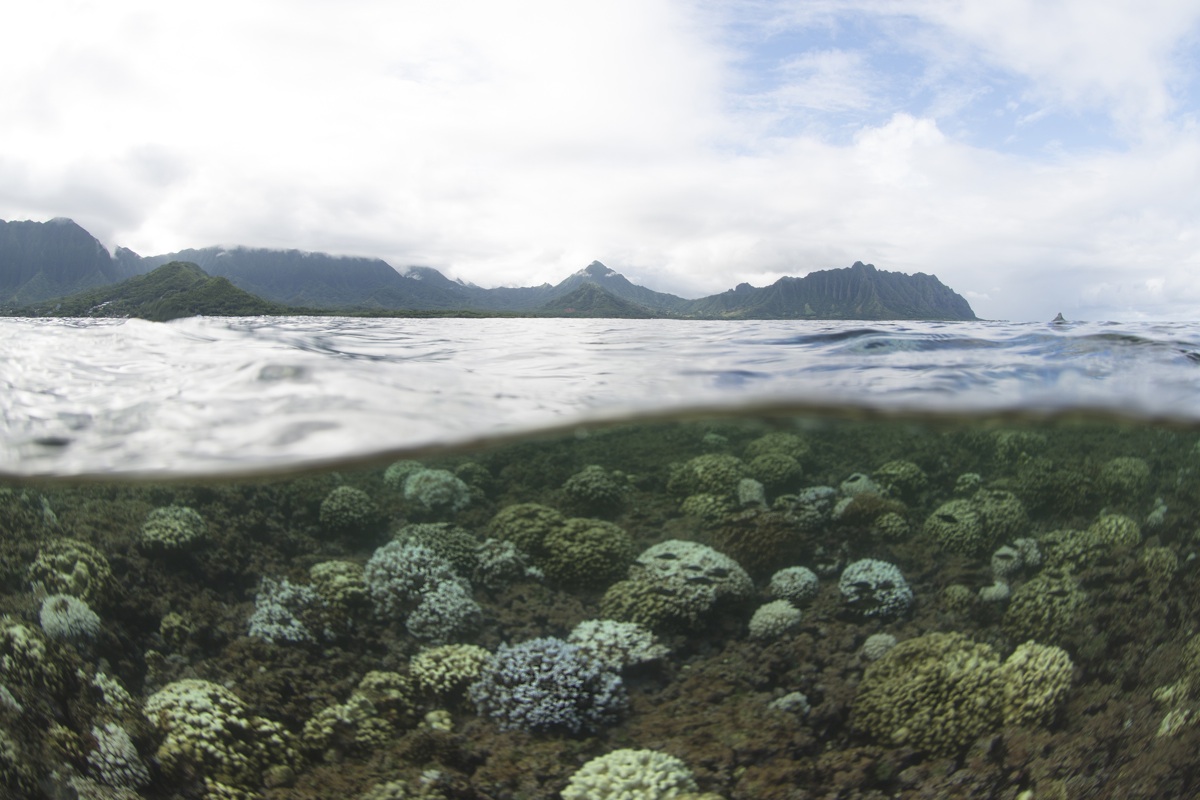

Kaneohe 'bones'

Bleached corals dot the floor of the famous Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii, along the coast of the Island of O'ahu, as seen in this image taken by the XL Catlin Seaview Survey. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Bad fish housing

As seen in early 2015, a reef in American Samoa turns drab during a bleaching event in which about 80 percent of this reef's corals died. Not all corals build reefs, but those that do start with free-swimming larvae. These little baby corals attached to a hard surface along the edges of islands or submerged rocks. As the colonial organism grows and expands, a reef is born. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Turtle love

A green turtle swims through a bleached reef in Hawaii, as seen in late 2014 during an XL Catlin Seaview Survey. "Coral reefs are among the most biologically diverse ecosystems on Earth," according to the Sea Turtle Conservancy. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Fish food?

A long-nose file fish — an iconic reef fish — struggles to find coral polys to eat. File fish are completely reliant on healthy corals for food. (Photo Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey)

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.