Upcoming El Niño May Be As Wild As 1997 Event

El Niño is expected to be more beast than "little boy" this year — a forecast about the weather pattern that becomes clear in newly released maps of the waters around the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

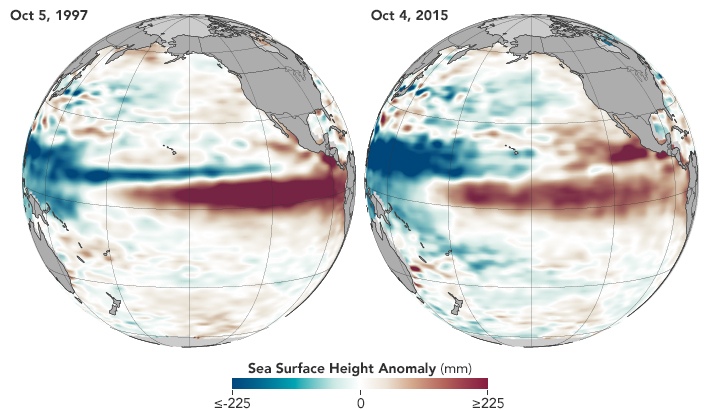

The two maps show the sea-surface heights in the Pacific in October 1997 and 2015, revealing that conditions this year are looking a lot like they did during the strong El Niño event of 1997 to 1998. Water expands as temperatures rise, and so sea-surface height is an indicator of warming in the upper layer of the ocean.

"Whether El Niño gets slightly stronger or a little weaker is not statistically significant now. This baby is too big to fail," Bill Patzert, a climatologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, told NASA's Earth Observatory.

During an El Niño — which translates as "The Little Boy" in Spanish — an ocean-atmosphere interaction leads to the warming of surface waters in the central and east-central Pacific around the equator. The cyclical phenomenon can affect wind and rainfall patterns worldwide. [How El Niño Causes Wild Weather All Over the Globe (Infographic)]

"Over North America, this winter will definitely not be normal. However, the climatic events of the past decade make 'normal' difficult to define," Patzert told the Earth Observatory.

Measurements of sea-surface heights in the newly released maps came from altimeters onboard the TOPEX/Poseidon satellite (1997) and the Jason-2 satellite (2015). The warmest waters, which are represented by sea-surface heights above normal sea level, can be seen (in red) moving into the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, while the colder-than-normal — or below-normal sea-surface heights — show up in blue in the western tropical Pacific Ocean.

Experts with the Climate Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, forecast last month that this year's El Niño could be among the strongest on record, dating back to 1950. In August, sea-surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean were near or greater than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) above the 1981 to 2010 average, according to the Climate Prediction Center.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The climate pattern is linked with snowy winters in the Northwestern United States and wet winters in the Southwest; drought in Southeast Asia and Australia typically accompany El Niño.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.