Oldest Draft of King James Bible Discovered, Historian Says

The King James Bible, the most widely read book in the English language — from which phrases like "a man after his own heart" emerged — is as storied as it is elusive. Now, a historian claims to have found the oldest known draft of the Christian text, written in messy script, in an obscure archive at the University of Cambridge.

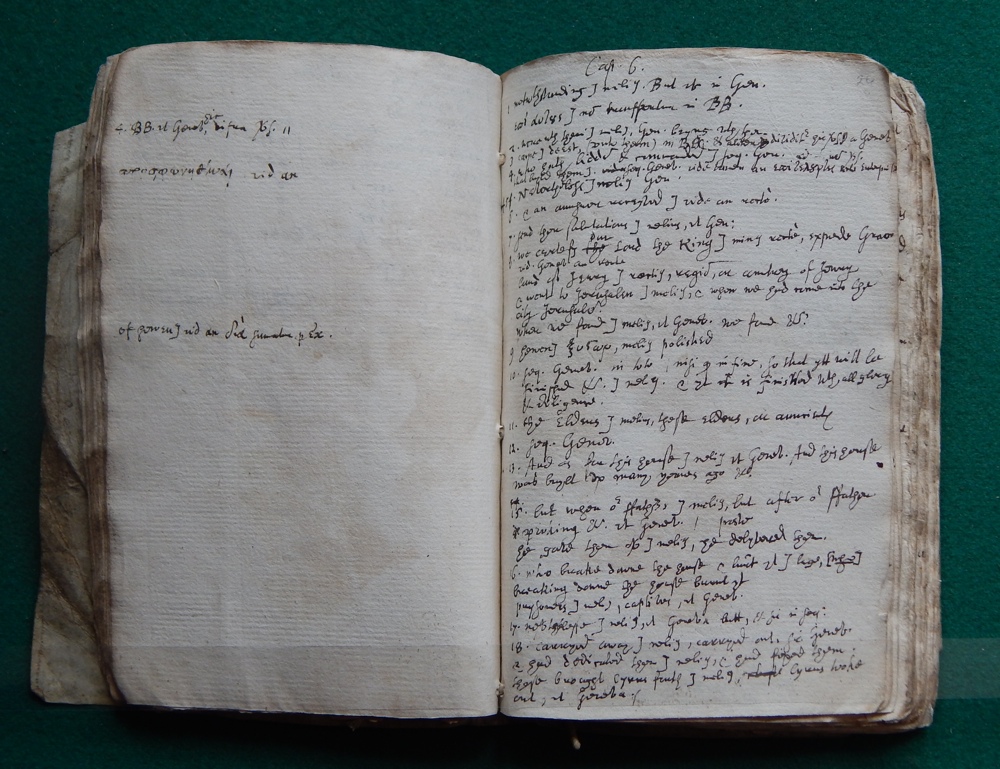

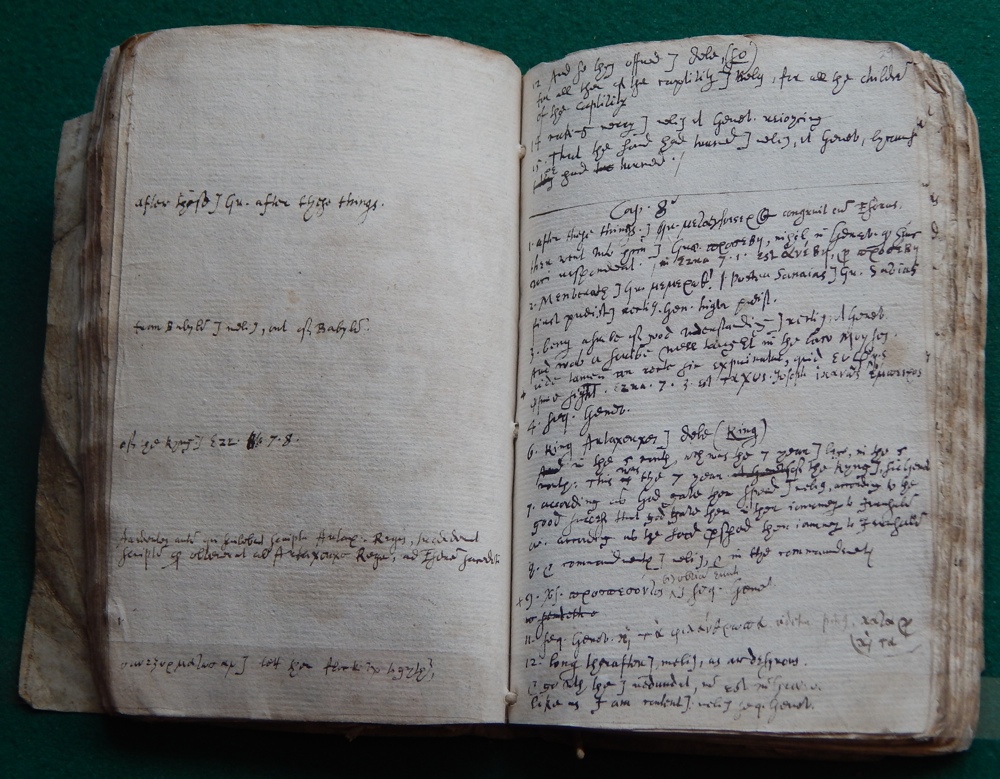

The manuscript was hidden among the papers of Samuel Ward, one of the men commissioned by King James I to translate a new version of the Christian text into English in the early 17th century.

Jeffrey Miller, an assistant professor of English at Montclair State University in New Jersey, chanced upon the 400-year-old notebook while doing research on Ward for an essay he's writing. The Eureka moment came when Miller realized that the notebook contained text from the very book that Ward had been commissioned to help translate. Miller recalled thinking, "Oh my gosh, he's talking about a book that he had been asked to help translate," he said. "Then I realized rather he was creating the King James Bible in that moment." [Proof of Jesus Christ? 7 Pieces of Evidence Debated]

Describing his discovery in the Times Literary Supplement, Miller said the notebook is not just the earliest draft ever found, but it is also the only surviving draft written in the hand of one of the original translators.

"Ward's draft alone bears all the signs of having been a first draft, just as it alone can be definitively said to be in the hand of one of the King James translators themselves," Miller wrote.

That hand was a messy one, it seems. "Ward's handwriting is notoriously bad," Miller told Live Science. "At least this is from earlier in his life," he added. Ward began his translation when he was just 32 years old, making him the youngest of the 54 or so men commissioned to translate the King James Bible; his handwriting only got worse with age, Miller noted. Luckily, Miller was familiar with Ward's handwriting from his intense study of the translator's texts.

Translating the Bible

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The King James Bible, first published in 1611, is one of the most influential and popular books in English literature. It spawned a long list of common phrases and figures of speech, such as "out of the mouths of babes," "at their wit's end" and "eat, drink and be merry." Even so, few documents survive from its translation.

"I think it is a fascinating discovery, and wholly credible," Jason BeDuhn, a professor of comparative study of religions at Northern Arizona University, told Live Science. "The more we can learn about the process by which the King James Bible was produced, the more realistic our assessment of its merits becomes."

King James tasked teams of translators in London, Cambridge and Oxford to write an English version of the Bible that would better reflect the principles of the Church of England. Ward was part of one those teams in Cambridge. He later became master of Sidney Sussex, one of the colleges within the University of Cambridge, and his scholarly papers ended up in the school's archives. In the 1980s, the notebook in question, catalogued as MS Ward B, had been labeled as a "verse-by-verse biblical commentary" with "Greek word studies, and some Hebrew notes." But when Miller revisited the text, he discovered that it actually contained notes and translations of parts of the Apocrypha, a disputed section of the Bible that is excluded from many versions today. [Religious Mysteries: 8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

"This discovery helps us recapture the human side of the translation process," BeDuhn said. "I especially like Prof. Miller's description of Ward trying out phrasing, crossing it out and trying something else. This is the real work of translation caught in the act."

According to Miller, Ward's notes show that he indeed grappled with the language of certain verses in the Apocrypha, for example, 1 Esdras 6:32. In the 16th-century Bishops' Bible, the previous version to be authorized by the English Church, 1 Esdras 6:32 describes a declaration of King Darius, which states that anyone found disobeying his decrees "of his own goods should a tree be taken, and he thereon be hanged."

"Proposing a revision to the front half of the passage, Ward at first began, 'A tre,' but then crossed it out," Miller explained. "No, 'out of h,' he started writing on second thought, but then crossed that out, too. At last, he reverted back to the more straightforward construction with which he had abortively begun, which also more closely mirrors the Greek of the passage: 'a tree should be taken out of his possession.'"

It seems Ward's suggestions were disregarded. The King James translation would ultimately read "out of his own house should a tree be taken, and he thereon be hanged."

Window into the past

The newly discovered notebook is not only the earliest known draft of any part of the King James Bible, but it's also the only known surviving draft of any part of the Apocrypha. Even so, Miller sees its legacy on a broader scale: "It points the way to a fuller, more complex understanding than ever before of the process by which the [King James Bible], the most widely read work in English of all time, came to be," he wrote.

Gordon Campbell of the University of Leicester agreed. "In short, Miller's discovery is a window into the translation process, and that makes it the most important discovery since Ward Allen unearthed the Corpus notebook sixty years ago," Campbell, a fellow in Renaissance studies, told Live Science, referring to an American scholar who, in the 1960s, tracked down the notes of one of the men tasked with revising the translations into the final King James Bible.

The discovery may also give researchers a model of what other drafts could look like.

"One of the things I hope is that the draft that I found leads us to discover more drafts of the King James Bible, because maybe we have a better idea of what that might look like," Miller said.

Jeanna Bryner, managing editor of Live Science, contributed to this article.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to include more information about the discovery.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.