Bloody Ancient Arrowhead Reveals Maya 'Life Force' Ceremony

An ancient arrowhead with human blood on it points to a Maya bloodletting ceremony in which a person's "life force" fed the gods, two researchers say.

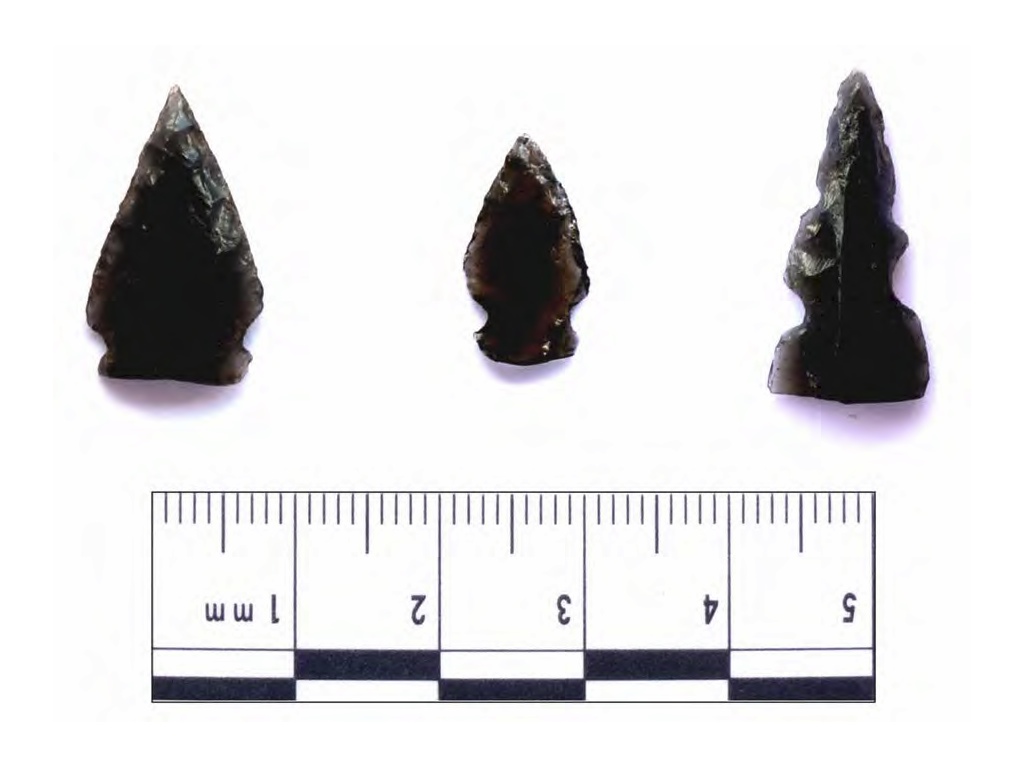

The ceremony took place around 500 years ago in Guatemala at a temple at the site of Zacpetén. During the ceremony someone was cut open — possibly through the earlobes, tongue or genitals — with an arrowhead made of obsidian (a volcanic glass), and their blood was spilled.

The Maya believed that each person had a "life force" and that bloodletting allowed this life force to nourish the gods. "The general consensus (among scholars) is that bloodletting was 'feeding' the gods with the human essential life force," said Prudence Rice, a professor emeritus at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. [Photos: Maya Mural Depicts Royal Advisors]

"We know Mayas also participated in bloodletting as a part of birth or coming-of-age ceremonies," said Nathan Meissner, a researcher at the Center for Archaeological Investigations at Southern Illinois University. "This practice served to ensoul future generations and connect their life force to those of past ancestors."

Whoever gave their blood may have done so voluntarily and probably survived the ceremony, Rice said.

Bloody finds

This life force ceremony was one of many discoveries made in a study published recently by Meissner and Rice in the Journal of Archaeological Science. For the study, they examined 108 arrowheads from five sites in the central Petén region of Guatemala. All the sites had been excavated within the last 20 years and all the arrowheads date to between A.D. 1400 and A.D. 1700.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using a technique called counter-immunoelectrophoresis they were able to detect the remains of ancient blood on 25 of the arrowheads and identify the types of species they came from. Two of the arrowheads had human blood, while the others held blood from a mix of animals, including rodents, birds, rabbits and large cats.

During the lab procedure, proteins are removed from the arrowheads and tests are conducted to see if the proteins react to serums containing the antibodies of different animals. If a reaction occurs, then it means the proteins from the arrowhead may be from the animal whose antibodies are being tested.

This technique "has been used occasionally in the last decade, but has some limitations because of cost, its potential for contamination, and its success rate," Meissner said. Quite often, ancient proteins don't survive the passage of time and the reactions don't always allow scientists to identify the precise species. For instance, while the researchers were able to tell that four of the arrowheads were coated with the blood of rodents, they couldn't identify what type of rodents were killed.

Combat casualty?

In the study, the researchers found that two arrowheads had human blood on them. The second arrowhead with human blood was discovered inside an old house near a fortification wall at Zacpetén. Impact damage on the arrowhead suggests it hit a person.

The researchers aren't clear on the story behind this arrowhead. A wounded individual (perhaps someone who was defending the site) may have been carried into the house, where the arrowhead was removed. "There are multiple accounts of Mayas surviving arrow injuries, which could mean they were brought back embedded in living individuals," Meissner said.

Another possibility is that the arrowhead hit someone in a skirmish and the arrow itself was then recycled. "The arrow could have been retrieved from a skirmish and brought back to the residence to reuse the arrow shaft, thus discarding the tip," Meissner said.

The project was funded by the National Science Foundation and was supported by the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala. The lab analysis was done at the Laboratory of Archaeological Science at the University of California at Bakersfield.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality