Aftermath of Gargantuan Landslide Captured in Space Image

A huge chunk of rock and ice slid down the flanks of Canada's Mount Steele on Oct. 11, at a dizzying speed — one estimate suggests a whopping 123 mph (nearly 200 km/h).

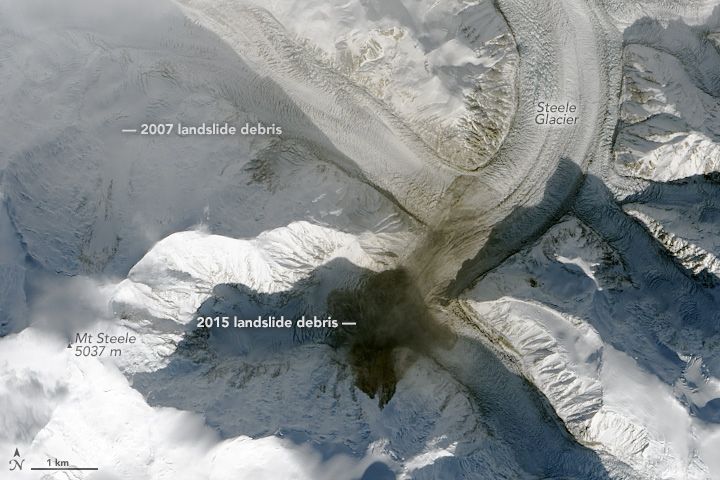

The aftermath of the gargantuan landslide — about 50 million tons (45 million metric tons) tumbled down the mountain — was captured in a stunning satellite image, released last week by NASA's Earth Observatory.

The fifth tallest mountain in Canada, Mount Steele is a major peak in the Saint Elias Mountains, towering over part of the southwestern Yukon Territory. And it's laced with seismometers meant to capture waves of energy that travel through Earth's crust as a result of earthquakes, landslides and other jolts in Earth. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

This month, cascading debris from the landslide sent seismic waves through Earth's crust. A global network of seismometers picked up the lengthy undulations (as opposed to the fast jiggles caused by earthquakes). Scientists from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University — Colin Stark and Göran Ekström — were alerted to the rumbling event when their rapid-detection software picked up that spike in seismicity, according to the Earth Observatory.

The seismic information pointed the scientists to a landslide in the area of Mount Steele. Then, on Oct. 13, the Operational Land Imager on the Landsat-8 satellite captured a snapshot of the landside's aftermath, visually confirming the titanic toppling. Comparing the new photo with a satellite image taken on Oct. 4, before the landslide, revealed a new streak of brown debris coating part of the subpeak of Mount Steele and a portion of Steele Glacier.

This long "debris field" is partly the result of the rubble tumbling onto an icy surface, according to the Earth Observatory.

"'Normal' landslides move a horizontal distance that is fairly similar to the height drop, but landslides on top of glaciers often have an elongated runout since the ice surface has low friction," said Columbia University's Stark, as reported by the Earth Observatory.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The slide itself was huge.

"This is a very large landslide," David Petley, a professor of geography at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email. "Outside of when there is a very large earthquake in a mountain chain, there are about 5-10 events of this magnitude per year worldwide." Petley estimates the debris traveled at a whopping 55 meters/second.

Not far from the Mount Steele landslide, another one sent 40 million tons of debris onto Turner Glacier on Aug. 11, according to Petley's Landslide blog. And in 2007, about 100 million tons, or the weight of all the cars in the United States, fell off Mount Steele in a giant slide, according to Ekström.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.