Facts About Salamanders

Salamanders are amphibians that look like a cross between a frog and a lizard. Their bodies are long and slender; their skin is moist and usually smooth; and they have long tails. Salamanders are very diverse; some have four legs; some have two. Also, some have lungs, some have gills, and some have neither — they breathe through their skin.

Salamanders belong to the order Caudata, one of three orders in the Amphibia class, along with Anura (frog and toads) and Gymnophiona (caecilians, which have no legs and resemble large worms). Within Caudata, there are nine families, 60 genera and about 600 species, according to the San Diego Zoo. Newts, mudpuppies, sirens and Congo eels (amphiumas) are all species of salamander.

Size

With hundreds of different types of salamanders, there are many different sizes. Most salamanders are around 6 inches (15 centimeters) long or less, according to the San Diego Zoo. The largest is the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus), which can grow up to 6 feet (1.8 meters) from head to tail and can weigh up to 140 lbs. (63 kilograms). The smallest is the Thorius arboreus, a species of pygmy salamander. It can be as small as 0.6 in (1.7 cm).

Habitat

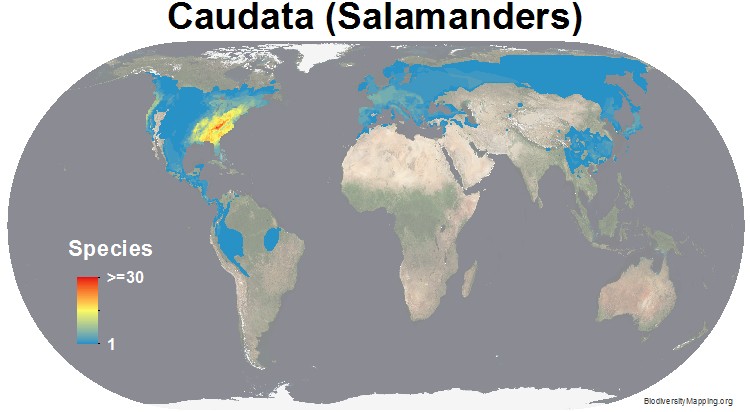

Salamanders live all over the world, but the United States has the largest number of different salamander families, according to the University of Michigan's Animal Diversity Web (ADW). All recognized families, except for Hynobiidae (Asiatic salamanders) are found in the United States.

The salamander’s habitat depends on what type of salamander it is. Newts typically spend most of their time on land, so their skin is dry and bumpy. Sirens have lungs as well as gills and spend most of their time in water. No matter the species, all salamanders need to keep their skin moist and need to have offspring in water, so a nearby water source is critical.

Most species live in humid forests, though there are some exceptions. The Iranian harlequin newt lives in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran, where there is only water for three or four months a year. During the wet times it mates and feeds, then goes into a deep sleep in a burrow during the dry times.

Some salamanders — 16 species, according to the San Diego Zoo — live in caves and have adapted to living in total darkness with very pale skin and greatly reduced eyes. [Album: Bizarre Frogs, Lizards and Salamanders]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Habits

Salamanders are typically more active during cool times of the day and are nocturnal. During the day they lounge under rocks or in trees to stay cool. At night they come out to eat.

Their bright, colorful skin warns predators to stay away, according to the San Diego Zoo. Many salamanders have glands on their necks or tails that secrete a bad-tasting or even poisonous liquid. Some can also protect themselves from predators by squeezing their muscles to make the needle-sharp tips of their ribs poke through their skin and into the enemy.

Some species can shed their tails during an attack and grow a new one. The axolotl, an aquatic salamander, can grow back limbs lost in fights with predators and damaged organs due to a special immune system.

Diet

Salamanders are carnivores, which means they eat meat instead of vegetation. They prefer other slow-moving prey, such as worms, slugs and snails. Some larger types eat fish, small crustaceans and insects. Some salamanders eat frogs, mice and even other salamanders.

Offspring

Many salamanders lay eggs, but not all. The alpine salamander and fire salamander give birth to live offspring, for example.

Depending on the species, other salamanders lay up to 450 eggs at a time. The Santa Cruz long-toed salamander, for example, lays 200 to 400 eggs at a time according to the ADW.

Spiny salamanders guard their eggs by curling their bodies around them. They also turn them over from time to time. Some newts wrap leaves around each egg to keep them safe.

Salamander eggs are clear and jelly-like, much like frog eggs. In fact, baby salamanders are just like baby frogs; their eggs are laid in water and the young are born without legs. Young salamanders in the larval stage are called efts, according to the San Diego Zoo. They resemble tadpoles, and as they get older, they grow legs.

Some salamanders don’t become sexually mature for up to 3 years and some live up to 55 years.

Classification/taxonomy

Here is the taxonomy of salamanders according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS):

Kingdom: Animalia Subkingdom: Bilateria Infrakingdom: Deuterostomia Phylum: Chordata Subphylum: Vertebrata Infraphylum: Gnathostomata Superclass: Tetrapoda Class: Amphibia Order: Caudata* Families: There are nine — Ambystomatidae, Amphiumidae, Cryptobranchidae, Hynobiidae, Plethodontidae, Proteidae, Rhyacotritonidae, Salamandridae and Sirenidae Genera and species: There are more than 600, including:

- Dicamptodon tenebrosus (Pacific giant salamander)

- Amphiuma tridactylum (three-toed amphiuma)

- Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi (Ozark hellbender)

- Ranodon sibiricus (Siberian salamander)

- Aneides vagrans (wandering salamander)

- Necturus maculosus (mudpuppy)

- Chioglossa lusitanica (golden-striped salamander)

- Cynops pyrrhogaster (firebelly newt)

*Some experts use Urodela and Caudata interchangeably as the name of the order. Some have suggested using Urodela to describe only extant, or living, forms, while using Caudata to include all known extant and fossil species, according to the ADW.

Conservation status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists hundreds of species on its Red List of Threatened Species. While some are listed as Least Concern for extinction because their populations are stable, most species on the list are vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered.

For example, the blunthead salamander, found in a small area of northwestern Mexico, is listed as critically endangered because the species is severely fragmented and the population is on the decline. Currently, there is no known population count. Similarly, Anderson's salamander, also of northwestern Mexico, is critically endangered due to pollution of the lake in which it lives.

Some species of salamanders are shrinking from generation to generation in response to climate change. According to researchers at the University of Maryland, salamanders that live in the Appalachian Mountains are shrinking because they must burn more energy as the local climate gets hotter and drier.

Additional resources

Correction: This article was updated on April 29, 2019 to reflect a correction. The original article incorrectly stated that all salamanders except one species lay eggs.