In Photos: Newfound Primate Had 'Goggle' Eyes and Tree-Climbing Arms

Scientists have uncovered the fossils of an 11.6-million-year-old primate that lived in what is now a province of Barcelona, Spain, where it walked on tree branches and ate fruit meals. Here's a look at the newbie and the site where it was discovered. [Read full story on the newfound primate.]

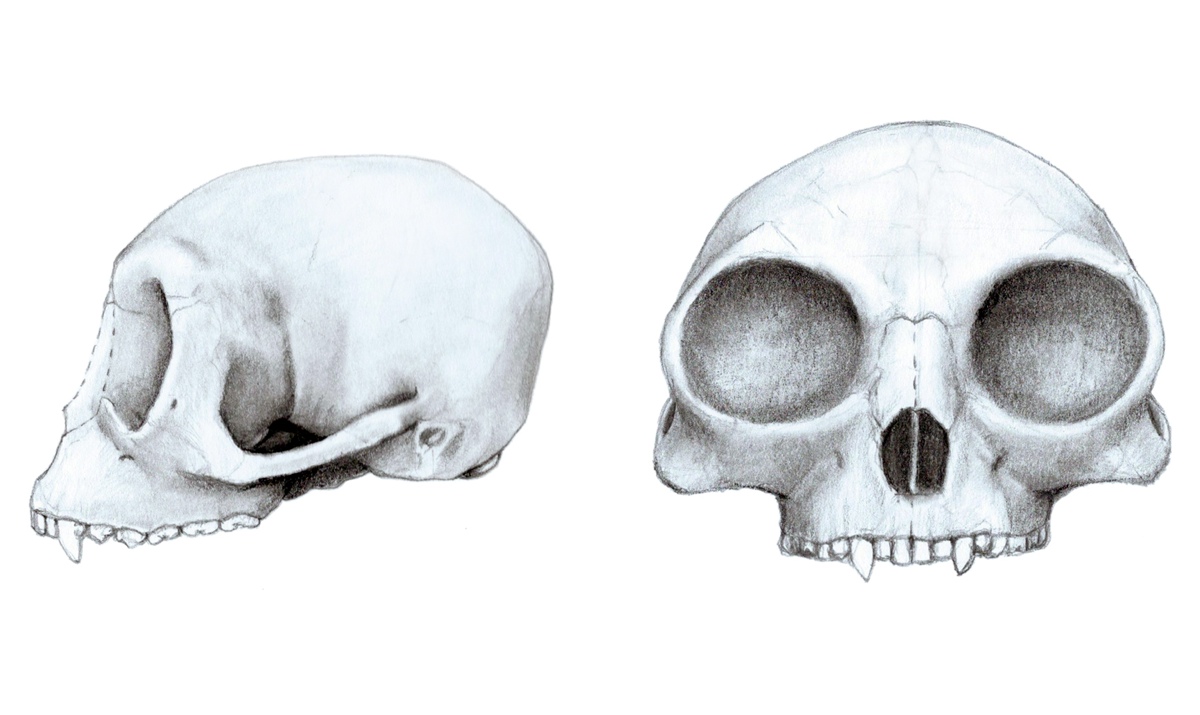

Little primate

The ancient primate, now dubbed Pliobates cataloniae, would've had a tiny head and body, shown here in an artist's representation. It lived during the Miocene in a warm, wet forest that was crisscrossed with rivers. (Photo Credit: Marta Palmero / Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)

Landfill discoveries

The researchers found the primate in 2011 during the enlargement of a landfill in Catalonia, a province in Barcelona, Spain. Here, a panoramic view of the Can Mata landfill (Els Hostalets de Pierola). The remains of the new hominoid were found in an area on the left in the image.

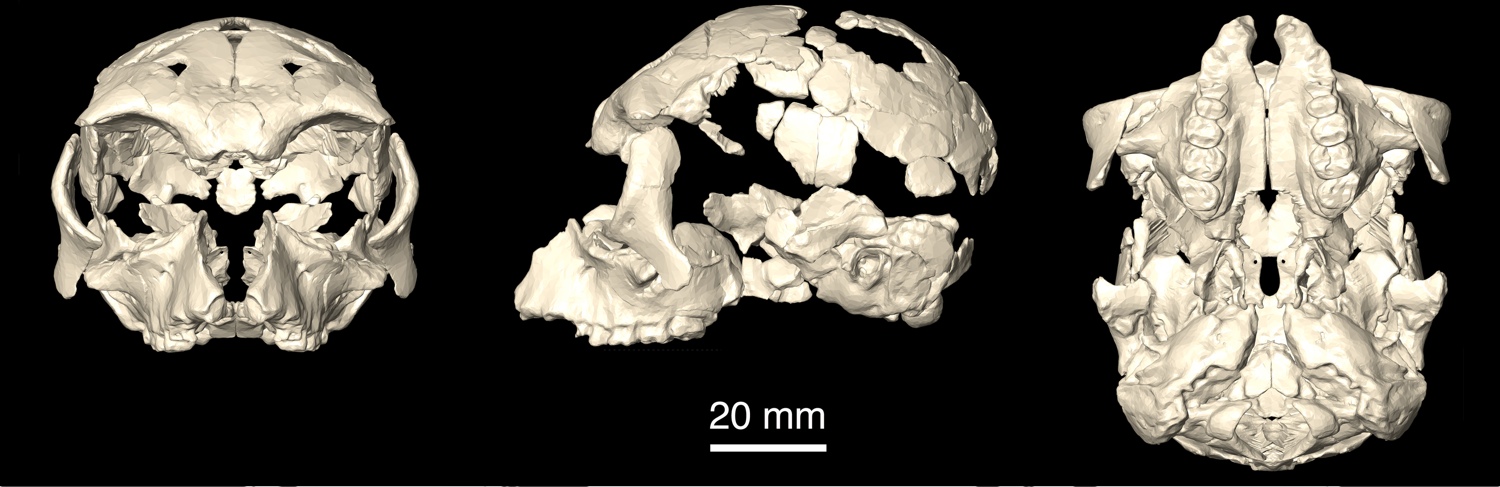

Little skull

The primate would have weighed about 8.8 to 11 lbs. (4 to 5 kilograms), making it similar in size to the smallest living gibbons. Here, a reconstruction of the skull of Pliobates cataloniae (the front and side view).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Virtual skull

Using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans, the researchers virtually reconstructed the skull of Pliobates cataloniae. Though its ears and teeth resemble primitive primates dating from before the split between hominoids and their closest monkey relatives, some of its facial features, like the gogglelike rims of the eye sockets, suggest it looked more like a gibbon. (Photo Credit: Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)

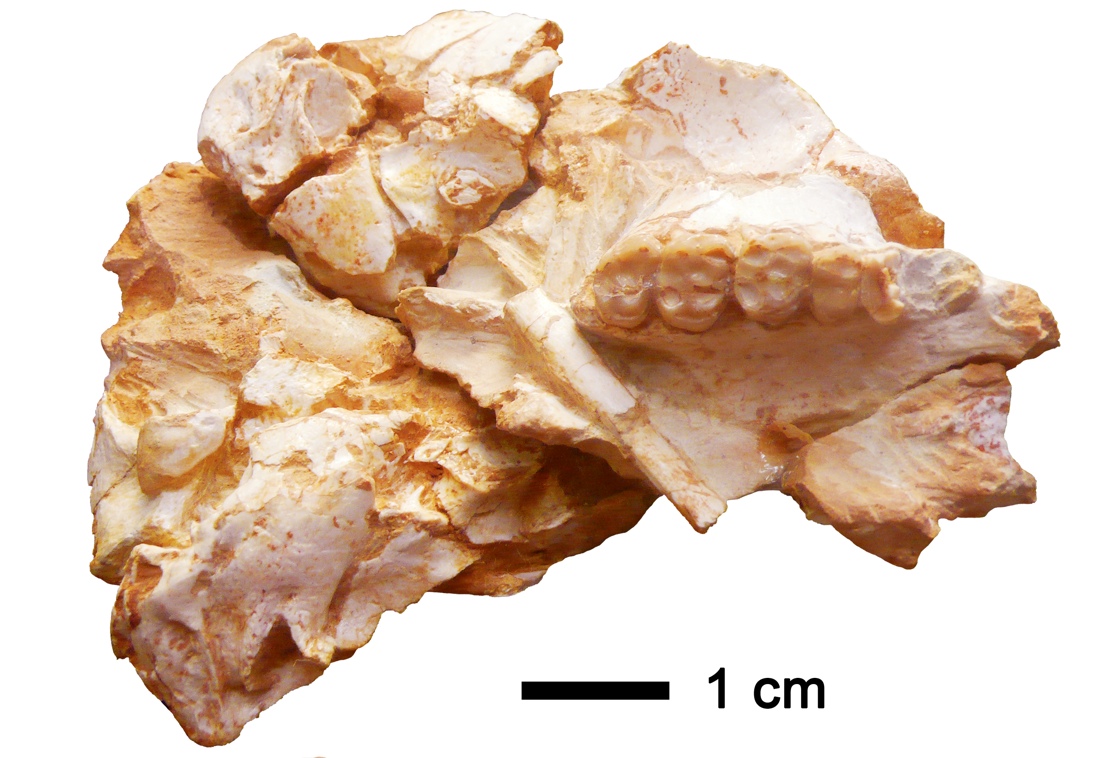

Fruity snacks

The primate likely snacked on fruits of the day. "Thanks to the microscopic marks left by food items on the surface of the teeth before the animal died we can infer that it basically consumed soft and ripe fruit like gibbons and most other extant hominoids," study lead author David Alba, a paleobiologist at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology at Barcelona, said in a video associated with the new paper published in the Oct. 30, 2015, issue of the journal Science. (Here the primate's cranium.) (Photo Credit: Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)

Tree walking

The scientists analyzed the primate's partial skeleton, which included 70 bones and bone fragments: most of the skull and teeth, and a good part of the left arm. Shown here, the long bones of the left arm, including the humerus (top), radius (middle) and ulna (bottom). The researchers said the species' limbs were designed for walking on the tops of branches and also hanging below them.

Lots of pals (and foes?)

P. cataloniae would have lived alongside a suite of other species in the warm, wet forest habitat. For instance, fossils found at the site reveal rodents, horses, rhinos, deer, proboscideans that distantly related to modern elephants and carnivores dubbed false saber-toothed cats. The diversity can be seen in this representation of the ecosystem of Els Hostalets de Pierola about 12 million years ago. (Image Credit: Oscar Sanisidro / Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.