Tiny Bird Fossil Solves Big Mystery About Life After Dinosaurs

This story was updated July 13 at 11:02 a.m. EDT.

A teeny-tiny fossilized bird skeleton is helping researchers understand the explosive rate at which birds diversified after the dinosaur age, new research shows.

The newfound, partial skeleton dates back to about 62.5 million to 62.2 million years ago, making it the oldest known modern bird specimen in North America, as well as the oldest known tree-dwelling bird to live after the nonavian dinosaur-killing mass extinction, the researchers said. Its mere existence suggests that birds rapidly evolved in the 4 million years after the dinosaurs died — much faster than previously thought, they said.

"Birds were explosively diversifying right after the end of the Cretaceous, right after the big mass extinction," said study co-author Tom Williamson, curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly (Gallery)]

Birds have a lengthy past. They began their evolutionary split from dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, about 150 million years ago. But like their scaly relatives, many bird lineages went extinct when a roughly 6-mile-long (10 kilometers) asteroid smashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

"Maybe a dozen or less lineages of birds survived," said study co-author Daniel Ksepka, curator of science at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut. (Today, there are about 40 lineages of birds that include more than 10,000 living species, he said.)

Without nonavian dinosaurs and the other extinct animals in the way, bird diversity suddenly skyrocketed, and the newfound skeleton shows just how quickly it did so, Ksepka told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Avian ancestor

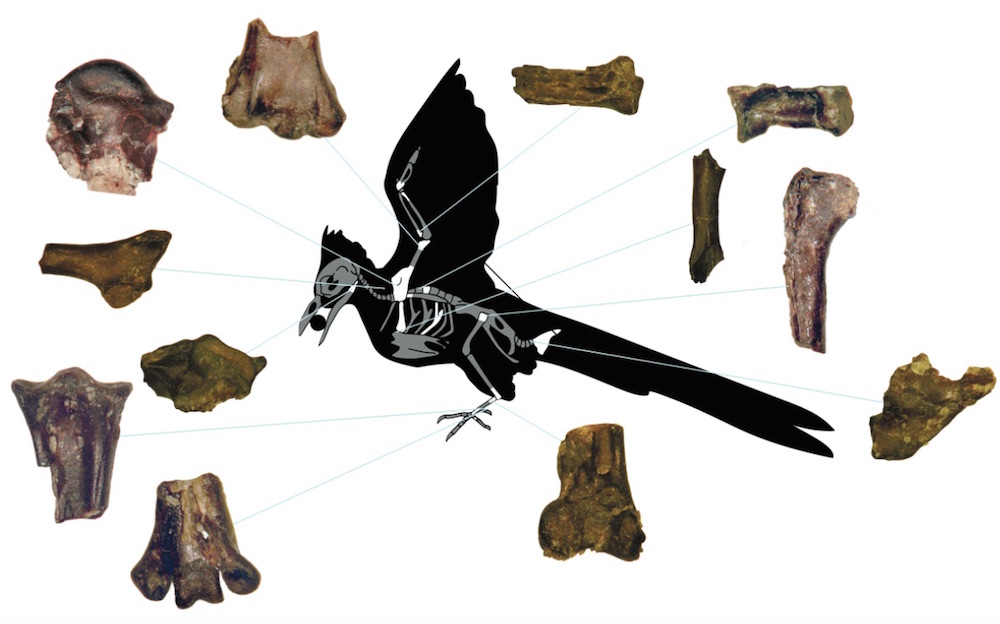

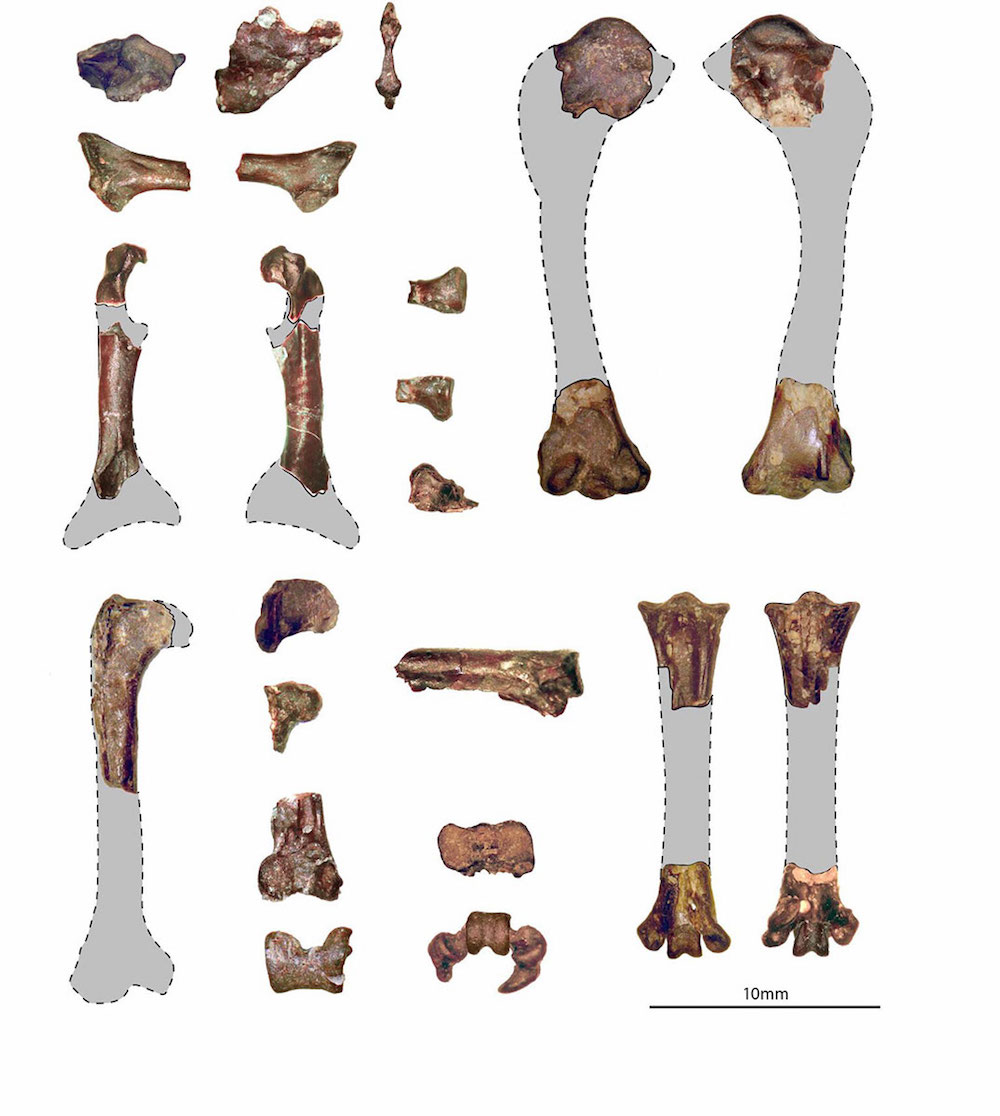

Williamson's 11-year-old twin sons found the site holding the delicate skeleton during a fossil dig in northwestern New Mexico's Nacimiento Formation in 2007. Williamson later excavated the fragmented bones, which are so small that the bird was likely no larger than a sparrow — smaller than the size of a human fist, he said.

The tiny bones piqued Williamson's interest, so he teamed up with Ksepka and Thomas Stidham, an avian paleontologist at the Institute for Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. The researchers analyzed the fossils, looking at more than 100 different size and shape characteristics.

They named the newfound species Tsidiiyazhi abini. The name is in Navajo, as the fossil was found within ancestral Navajo lands, the researchers wrote in the study. The genus name combines the Navajo words "tsidii" for "bird" and "yazhi" for "little," in reference to the bird's small size. The species name "abini" means "morning," a nod to the bird's early occurrence. In essence, the name translates to "little morning bird," the researchers said.

An analysis revealed that T. abini is an ancient species in the order of Coliiformes, or mousebirds — a group of small, long-tailed birds. Today, there are just six species of Coliiformes that live only in sub-Saharan Africa, the researchers said.

Furthermore, T. abini had semizygodactyl feet, meaning that it had the ability to turn its fourth, outer toe backward or forward. "This is important for things like climbing or grasping onto objects like branches," Ksepka said. "A fully zygodactyl bird would have the fourth toe permanently reversed" with two toes pointing forward and two toes pointing backward, like a woodpecker, he said.

The foot finding suggests that semizygodactyly evolved independently in three different clades (groups), and were not a necessary step to full zygodactyly, the researchers said.

Rapid radiation

If this tiny, newfound bird was already living around 62 million years ago, it suggests that as many as nine major bird clades developed earlier than previously thought. For instance, the new evidence indicates that the mousebird evolved some 6 million years earlier than researchers had thought, Ksepka said.

"This bird has some wide implications for the timing of the radiation [diversification] of modern birds," Ksepka said. But "to pinpoint exactly when these birds are popping up, we really need the fossil record," he added.

In 1980, a group of researchers in New Zealand discovered the fossilized skeleton of a penguin (Waimanu manneringi) that dates to between 60.5 million and 61.6 million years ago.

"Together, the new bird and Waimanu show that the diversifications of aquatic and terrestrial birds were both well underway just a few million years after the mass extinction that hit 66 million years ago," Ksepka said.

In fact, the compressed but explosive 4-million-year diversification that modern birds likely underwent after the end-Cretaceous extinction is similar to the diversification of placental mammals, which also rapidly diversified after the nonavian dinosaurs died, he said.

The study was published online July 10 in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Editor's note: This story was originally published on Oct. 29, 2015, after the researchers presented their preliminary findings at the 75th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference in Dallas. Now that the study is published in a peer-reviewed journal, Live Science has updated the story to include the species' scientific name and that the bird was semizygodactyl and the oldest tree-dwelling bird on record.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.