Although actor Robin Williams died by suicide, the underlying cause of his death was a rare brain disease called Lewy body dementia, according to his widow.

The disease caused Williams to experience hallucinations and other debilitating neurological symptoms, including depression, Susan Schneider Williams, widow of the late actor, told People magazine in a recent interview. An autopsy released in 2014 confirmed that the actor had the disease, but this is the first time that his condition has been discussed in detail.

"It was not depression that killed Robin," Schneider Williams said in the interview. "Depression was one of, let's call it 50 symptoms, and it was a small one."

But whereas other neurological disorders are well known, few people have heard of Lewy body dementia. Though the disease can cause symptoms similar to those seen with Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body dementia is caused by the abnormal buildup of a different protein from the one that is linked with Alzheimer's. [10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp]

Lewy body dementia

Lewy body dementia was discovered in the early 1900s, when researcher Frederic Lewy, who worked in the laboratory of neurologist Alois Alzheimer, found the abnormal buildup in the brain tissue of dementia patients.

Today, the disease affects 1.4 million Americans, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association. A 2013 study in the journal Archives of Neurology (now JAMA Neurology) found that men are about twice as likely as women to develop the disease.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

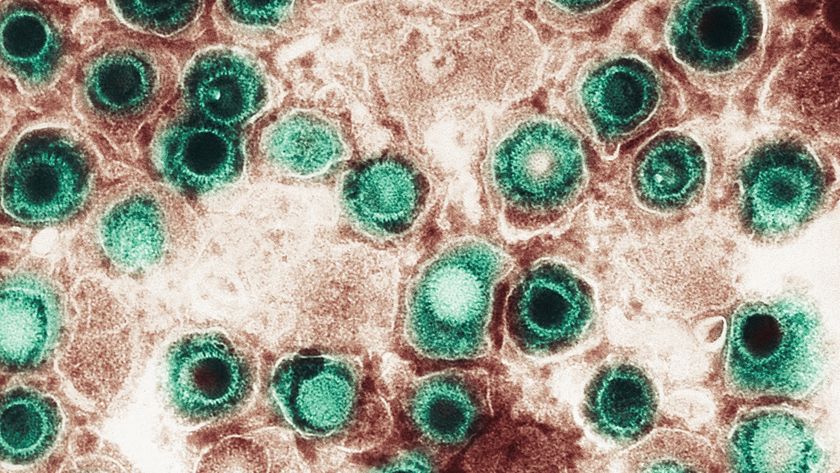

The condition occurs when Lewy bodies, or clumps of a protein called alpha synuclein, build up in the brain. No one knows why Lewy bodies accumulate, but they are also found in the brains of people with Parkinson's disease, and in the brains of those with Alzheimer's.

Myriad symptoms

Lewy body dementia can cause visual hallucinations; rigid movements and motor problems similar to those found in people with Parkinson's disease; sleep disorders; anxiety; interruptions in the ability to pay attention; and loss of memory, according to the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke. As in Williams' case, the disease can also fuel depression.

Lewy body dementia can mimic other diseases, such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Researchers are still trying to figure out how Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia may be related. Although abnormal processing of alpha-synuclein plays a role in both diseases, Parkinson's disease seems to preferentially occur in a brain area called the substantia nigra, an almond-shaped region in the mid-brain responsible for reward, addiction and movement, whereas Lewy body dementia tends to occur more diffusely, throughout the brain, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

Still, up to 80 percent of Parkinson's patients go on to develop some type of dementia, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

Currently, if people develop the movement disorder known as Parkinsonism and then do not develop dementia within a year, they are diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. If they do develop dementia within the year, their condition is classified as Lewy body dementia, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

There is no cure for Lewy body dementia, and the disease is progressive, meaning it gets worse over time. Most treatments focus on controlling symptoms, such as hallucinations or sleep disturbances. However, a 2010 study published in the journal The Lancet Neurology found that a drug called memantine, which is used to slow the loss of cognitive abilities in people with Alzheimer's, can also improve symptoms in people with Lewy body dementia and Parkinson's disease.

People with Lewy body dementia typically live about eight years after their diagnosis, according to the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.