Mysterious Dark Matter May Not Always Have Been Dark

Dark matter particles may have interacted extensively with normal matter long ago, when the universe was very hot, a new study suggests.

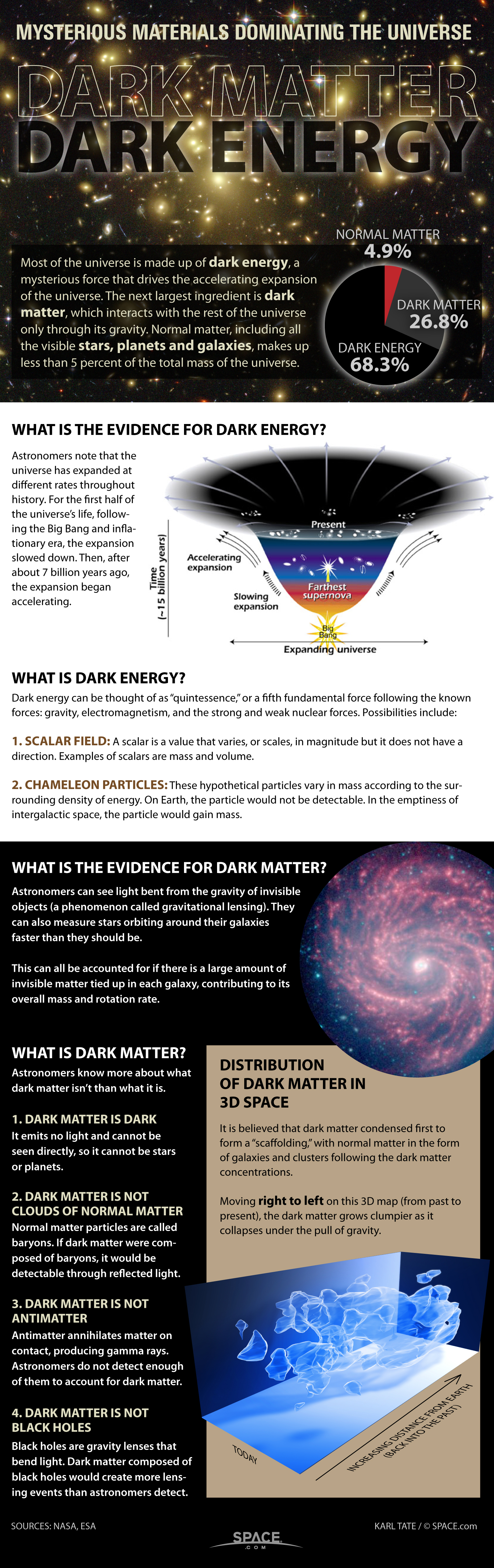

The nature of dark matter is currently one of the greatest mysteries in science. The invisible substance — which is detectable via its gravitational influence on "normal" matter — is thought to make up five-sixths of all matter in the universe.

Astronomers began suspecting the existence of dark matter when they noticed the cosmos seemed to possess more mass than stars could account for. For example, stars circle the center of the Milky Way so fast that they should overcome the gravitational pull of the galaxy's core and zoom into the intergalactic void. Most scientists think dark matter provides the gravity that helps hold these stars back. [Gallery: Dark Matter Throughout the Universe]

Scientists have mostly ruled out all known ordinary materials as candidates for dark matter. The consensus so far is that this missing mass is made up of new species of particles that interact only very weakly with ordinary matter.

One potential clue about the nature of dark matterhas to do with the fact that it's five times more abundant than normal matter, researchers said.

"This may seem a lot, and it is, but if dark and ordinary matter were generated in a completely independent way, then this number is puzzling," said study co-author Pavlos Vranas, a particle physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California. "Instead of five, it could have been a million or a billion. Why five?"

The researchers suggest a possible solution to this puzzle: Dark matter particles once interacted often with normal matter, even though they barely do so now.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

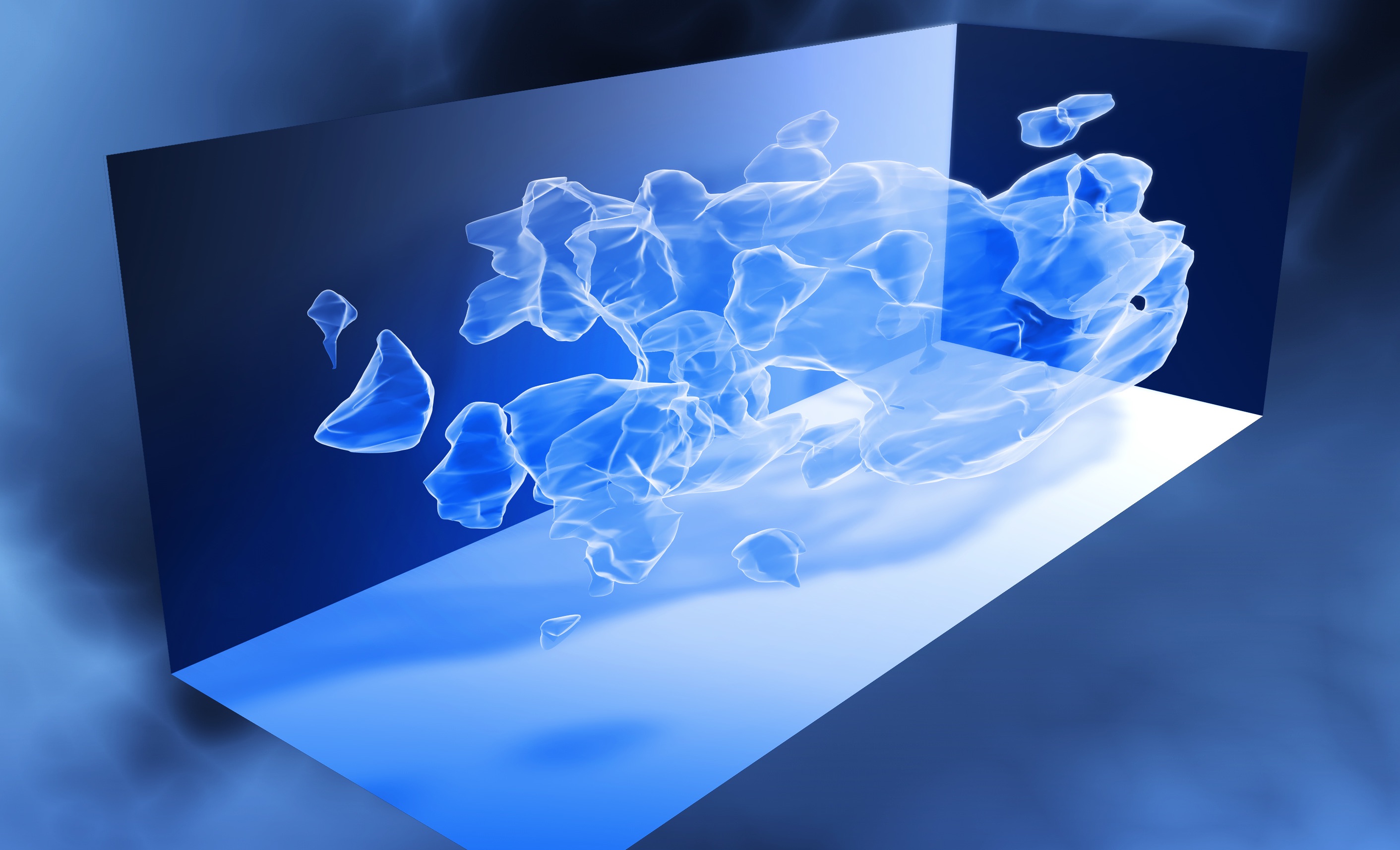

"This may have happened in the early universe, when the temperature was very high — so high that both ordinary and dark matter were 'melted' in a plasma state made up of their ingredients," Vranas told Space.com.

The protons and neutrons making up atomic nuclei are themselves each made up of a trio of particles known as quarks. The researchers suggest dark matter is also made of a composite "stealth" particle, which is composed of a quartet of component particles and is difficult to detect (like a stealth airplane). The scientists' supercomputer simulations suggest these composite particles may have masses ranging up to more than 200 billion electron-volts, which is about 213 times a proton's mass.

Quarks each possess fractional electrical charges of positive or negative one-third or two-thirds. In protons, these add up to a positive charge, while in neutrons, the result is a neutral charge. Quarks are confined within protons and neutrons by the so-called "strong interaction."

The researchers suggest that the component particles making up stealth dark matter particles each have a fractional charge of positive or negative one-half, held together by a "dark form" of the strong interaction. Stealth dark matter particles themselves would only have a neutral charge, leading them to interact very weakly at best with ordinary matter, light, electric fields and magnetic fields.

The researchers suggest that at the extremely high temperatures seen in the newborn universe, the electrically charged components of stealth dark matter particles could have interacted with ordinary matter. However, once the universe cooled, a new, powerful and as yet unknown force might have bound these component particles together tightly to form electrically neutral composites.

Stealth dark matter particles should be stable — not decaying over eons, if at all, much like protons. However, the researchers suggest the components making up stealth dark matter particles can form different unstable composites that decay shortly after their creation.

"For example, one could have composite particles made out of just two component particles," Vranas said.

These unstable particles might have masses of about 100 billion electron-volts or more, and could be created by particle accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) beneath the France-Switzerland border. They could also have an electric charge and be visible to particle detectors, Vranas said.

Experiments at the LHC, or sensors designed to spot rare instances of dark matter colliding with ordinary matter, "may soon find evidence of, or rule out, this new stealth dark matter theory," Vranas said in a statement.

If stealth dark matter exists, future research can investigate whether there are any effects it might have on the cosmos.

"Are there any signals in the sky that telescopes may find?" Vranas said. "In order to answer these questions, our calculations will require larger supercomputing resources. Fortunately, supercomputing development is progressing fast towards higher computational speeds."

The scientists, the Lattice Strong Dynamics Collaboration, will detail their findings in an upcoming issue of the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.