Dog-Size Rats Once Lived Alongside Humans

Rats as big as dachshunds once lived alongside humans — who frequently ate the robust rodents, according to a recent study.

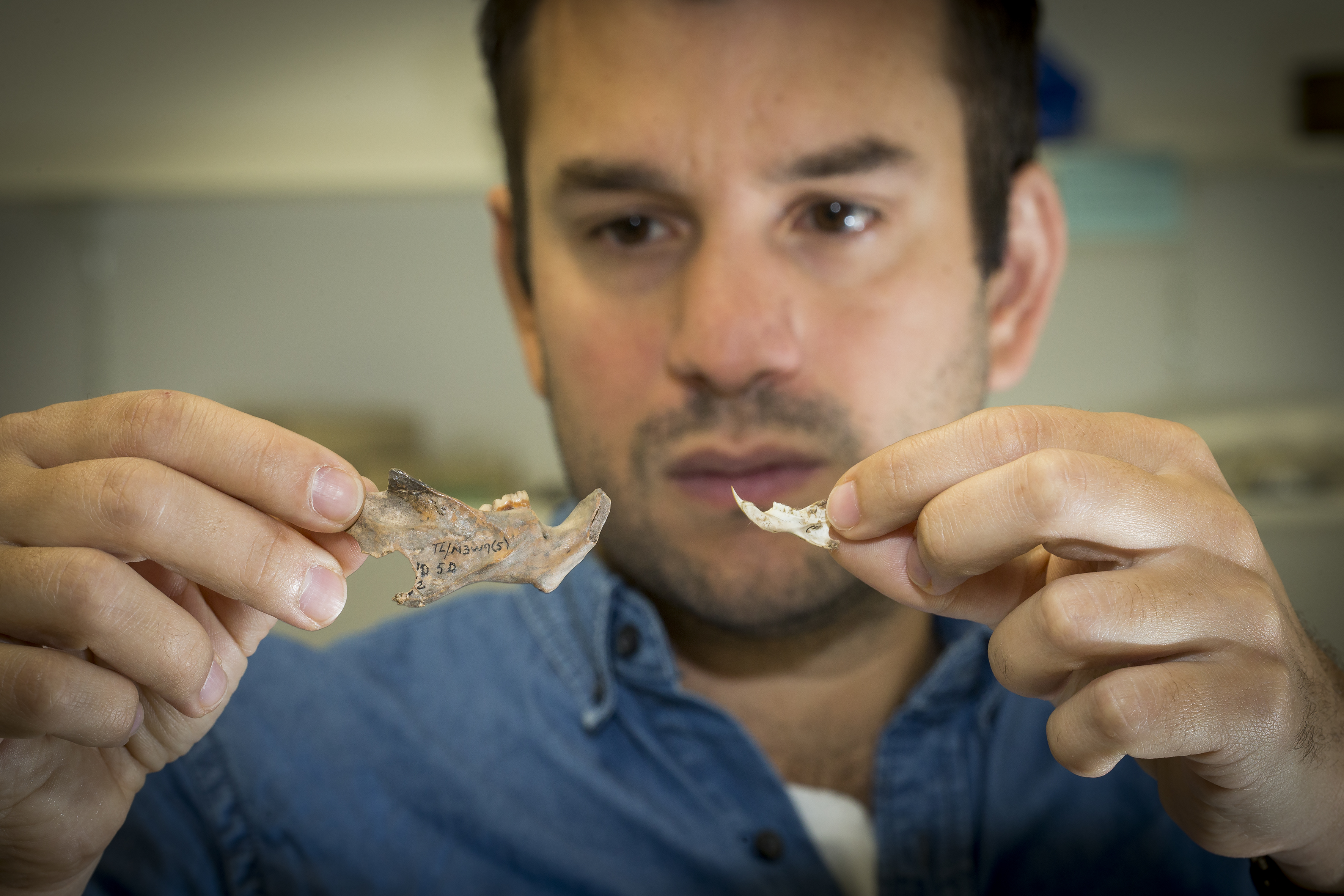

Scientists on an expedition to the island nation of East Timor discovered fossils representing seven new species of giant rats, all larger than any species ever found. The biggest of them would have tipped the scales at 11 lbs. (5 kilograms), about 10 times as much as a modern rat, according to Julien Louys, a paleontologist and research fellow at the Australian National University, who presented the findings in October at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Them bones

Calling the dig sites fossil-rich would be an understatement, Louys told Live Science. Over several years, researchers recovered thousands of bones belonging to an assortment of rat species. "Even in one 5-centimeter [1.9 inches] chunk of ground, you would usually find a dozen or half-dozen bones," he said. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Based on evidence from other rat fossils on the island, Louys estimated the giant rats arrived about 1 million to 2 million years ago, though it's difficult to say for sure. The earliest giant rat fossils were discovered in archaeological deposits dating back 46,000 years, suggesting the rats and humans lived together. Signs of burns and cut marks on the rat bones suggested humans were butchering the rats and cooking them for food.

Humans and the giant rats continued to interact for thousands of years with no dramatic changes in the rat populations, the researchers said. Perhaps the density of local vegetation and the size of the island protected the rats. On the Canary Islands, which were smaller than East Timor and had less forest cover, giant rats weren't so lucky, and were wiped out within a few hundred years after people arrived.

But even on East Timor, the giant rats' days were numbered. Around 1,000 years ago, all evidence of the sizable rodents vanished. Their decline coincided with the arrival of metal tools, which decimated large swathes of dense canopy rainforest where the rats lived. "When metal tools were developed, massive deforestation followed. This is the best working hypothesis for the rats' extinction," Louys said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The relationship between these extinct rats and long-dead humans tells an important story: how human migration affected an ecosystem. By studying evidence from the region that predates human arrival and comparing it to the aftermath, scientists can gauge the impact of human intervention. In this case, as in the Canary Islands, a species of rodent giants disappeared forever.

Kind of a big deal

Some giant rat species do survive today, though none is as large as the ones found by Louys and his colleagues. In Papua New Guinea, Flores (an island in Indonesia) and the Philippines, some species of rats can weigh up to 6.6 lbs. (3 kg). They are elusive, and little is known about their biology. But supersized rodents like the East Timor giant rats were once common, roaming the continents for millions of years during the Pleistocene epoch, from about 1.8 million to about 11,700 years ago.

Many of those rodents were enormous. Castoroides, an extinct genus of North American giant beaver, weighed up to 220 lbs. (100 kg). Giant hutias, guinea-piglike creatures that used to inhabit the West Indies, could weigh as much as 440 lbs. (200 kg). Josephoartigasia monesi, the biggest rodent that ever lived, weighed as much as 3,382 lbs. (1,534 kg) with the girth of a small hippo.

Louys added that time will tell if the giant rats of East Timor have relatives nearby —living or extinct. Future expeditions will explore other islands in the area, which are yet to be surveyed in detail and may contain not only fossil evidence of similar giant rats from thousands of years ago, but may harbor living rats far bigger than their urban cousins that haunt our subways and occasionally swipe our pizza.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.