El Niño Expected to Strengthen, Bring Wild Weather Across US

El Niño is likely to strengthen by the end of the year, potentially bringing more precipitation than usual to much of the United States.

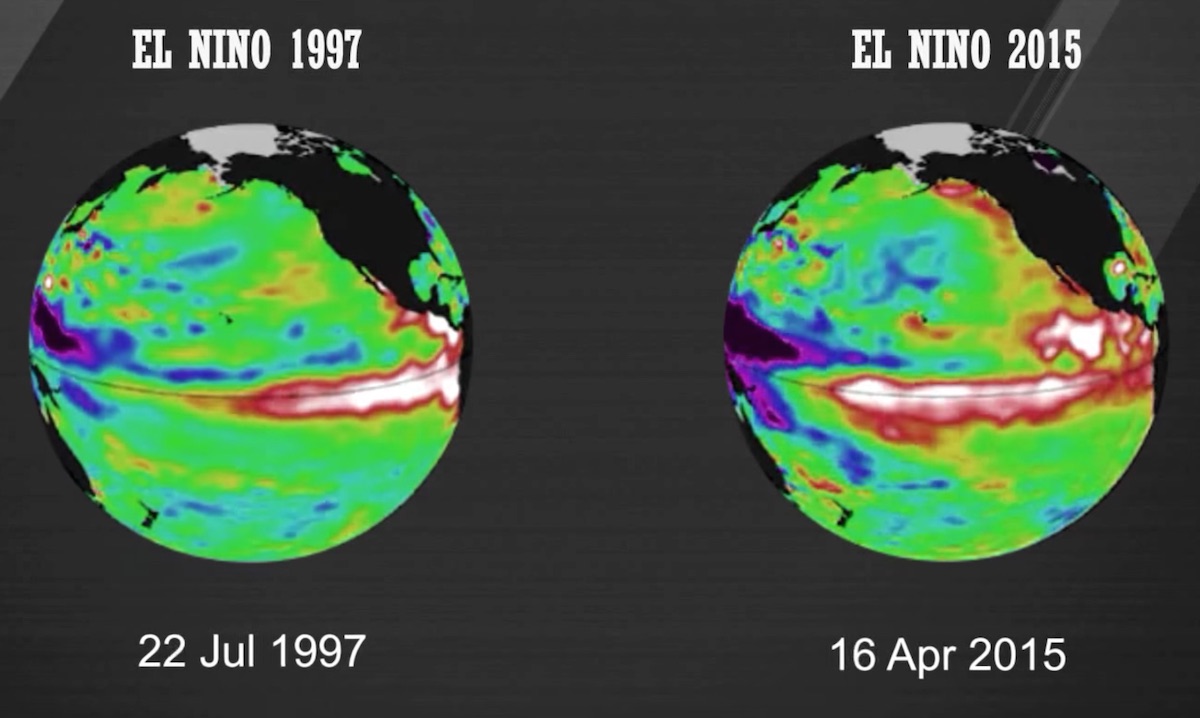

This year's El Niño is among the strongest since 1950, according to meteorologists. Already, the atmospheric pattern is among the top three since that time, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

The organization's latest update warns that peak three-month average surface water temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific are more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal. El Niño is a climate pattern that brings warm water to the western shores of South America. This warm water is prone to evaporation, fueling a moister atmosphere that boosts Pacific hurricanes such as Patricia, the October storm that grew to be the most powerful tropical cyclone ever measured in the Western Hemisphere. [How El Niño Causes Wild Weather All Over the Globe (Infographic)]

However, the effects of El Niño are complex. While the southern half of the United States usually gets soggier with El Niño, some regions — including Hawaii, Australia, India and Brazil, among other places — become more prone to drought, according to the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln.

The current El Niño ranks among those in 1972-1973, 1982-1983 and 1997-1998 as one of the strongest on record, according to the WMO. Already, the effects are apparent.

"Severe droughts and devastating flooding being experienced throughout the tropics and subtropical zones bear the hallmarks of this El Niño, which is the strongest for more than 15 years," WMO Secretary-General Michel Jarraud said in a statement. El Niño typically reaches peak strength between October and January.

Predicting weather patterns in particular regions in this strengthening El Niño is difficult, however, because the pattern is only one of several that affect global weather. The tropical Atlantic sea surface temperature and the oscillations in temperature of the Indian Ocean play roles in determining temperature and precipitation as well, according to the WMO. The situation is further complicated by the backdrop of global climate change, which has melted Arctic summer ice and snow, and heated up the ocean surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"[T]his naturally occurring El Niño event and human-induced climate change may interact and modify each other in ways which we have never before experienced," Jarraud said. "Even before the onset of El Niño, global average surface temperatures had reached new records. El Niño is turning up the heat even further."

One 2010 study found that climate change may shift warm waters from the eastern equatorial Pacific to the central Pacific, which, in turn, could completely alter the atmospheric patterns El Niño brings.La Niña, a separate weather pattern that typically involves cooler-than-usual waters in the equatorial Pacific, may become more extreme with global warming, according to research released this year in the journal Nature Climate Change. Extreme La Niña events often occur after extreme El Niño events because El Niño releases heat from the ocean into the atmosphere, Wenju Cai, the author of that study and a climate scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia, told Live Science at the time. The result is atmospheric circulation that cools the equatorial Pacific.

La Niña can cause drought in the southern United States and flooding in the areas that El Niño typically dries out, meaning that if this pattern of extreme El Niño to extreme La Niña sets up, the globe could be in for a wild ride over the next several years.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.