Weird Sea Mollusk Sports Hundreds of Eyes Made of Armor

A marine mollusk built like a tiny tank can see with eyes made of the same material as its armor.

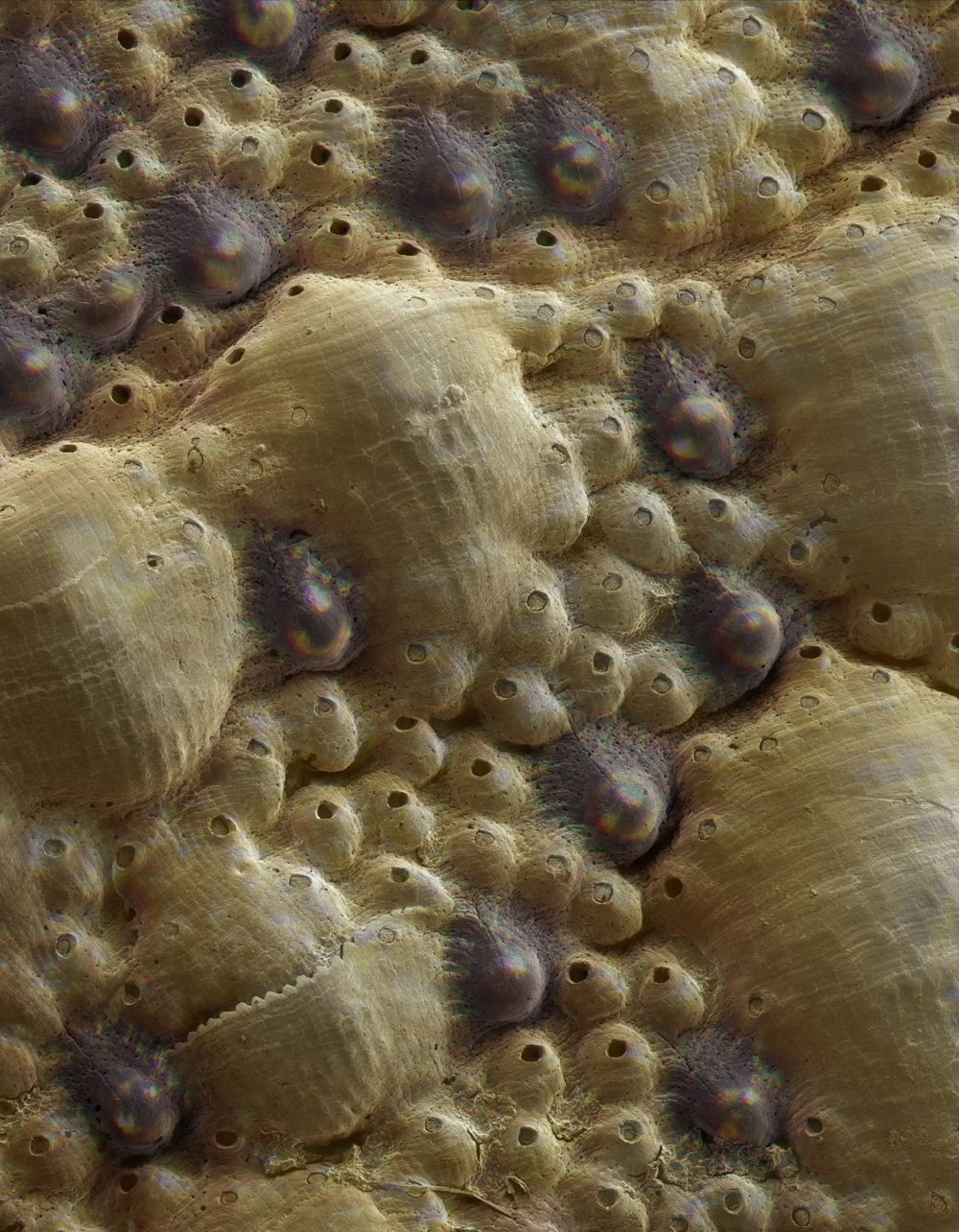

Acanthopleura granulata is a chiton, a pill bug of the sea. This animal has a shell made of overlapping plates, which allows it to roll up in defense if a predator manages to pry it from the tidal-zone rock it calls home. Researchers have long known that chitons have soft tissue embedded in their flexible suits of armor, and that some of this soft tissue is sensitive to light. Now, they've discovered that A. granulata has hundreds of actual eyes that can see an 8-inch-long (20 centimeters) fish from 6.5 feet (2 meters) away.

Even weirder, these eyes are made of the same calcium-carbonate mineral as the chiton shell. However, the animal does have to trade off some structural integrity in return for the sensory function.

"We think this system might provide design lessons for us to learn how nature is able to produce material structures with multiple different functions," said Ling Li, one of the authors of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. [7 Cool Animal-Inspired Technologies]

Natural inspiration

Ling and the rest of the research team have studied multiple animals with bizarre multitasking armor and exoskeletons. Brittle stars, which are relatives of sea stars (also called starfish), have light-sensing lenses built into their exoskeletons. Some limpets have structurally special areas in their otherwise translucent shells that create colorful displays. Windowpane oysters have nearly transparent shells that nevertheless are extremely strong.

The goal, Li told Live Science, is to use nature's designs for improvements in engineering and technology. Windowpane oysters, for example, might inspire stronger windshields for combat vehicles. And chiton shells could provide a basis for creating self-monitoring materials, such as walls embedded with sensors that would detect cracks, Li said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new work, published in the Nov. 20 issue of the journal Science, reveals that chiton eyes are very different from human eyes. Whereas human eyes are made of proteins, chiton eyes are made of aragonite, a mineral. Aragonite is a kind of calcium carbonate found in many mollusks. Pearls, created by oysters, are a mix of aragonite and a protein called conchiolin.

The researchers examined the microscopic structure of these aragonite eyes, comparing them with the surrounding armor structure. They also ran experiments and simulations to reveal that the eyes are more than just light-sensitive spots; they actually resolve images. From more than 6 feet away, chitons can see a blur representing a small fish. This gives them time to clamp down hard on the rock below so the potential predator can't dislodge them, Li said.

Functional trade-offs

Sight has its costs, though. The researchers found that the aragonite eye structures are not as strong as the surrounding armor. Though the two are made of the same mineral, the aragonite in the eyes has a different crystalline structure. That different structure, along with a pore space beneath the eyes, makes them weaker. Thus, they fracture more easily.

"It's a compromise," Li said.

Chitons have come up with a few protective strategies, the researchers found. The eye structures are clustered in tiny "valleys" in the mollusk's armor, which help keep them safe. Their underlying layers seem to be hard and thick, so that any damage doesn't penetrate fully. And chitons have up to 1,000 eyes and can grow more throughout their lifetimes, replacing any that are damaged.

Humans are a long way from being able to replicate this natural system, Li said, because fabricating such intricate microscopic structures is still impossible. Eventually, though, manufacturers might be able to 3D-print structural panels with built-in optical capabilities.

"The next step would be looking at the formation process of this system," Li said. And researchers still need to find out how these simple little mollusks integrate information from the hundreds of eyes dotting their bodies.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular