Cause of Mysterious Snake Die-Off Found

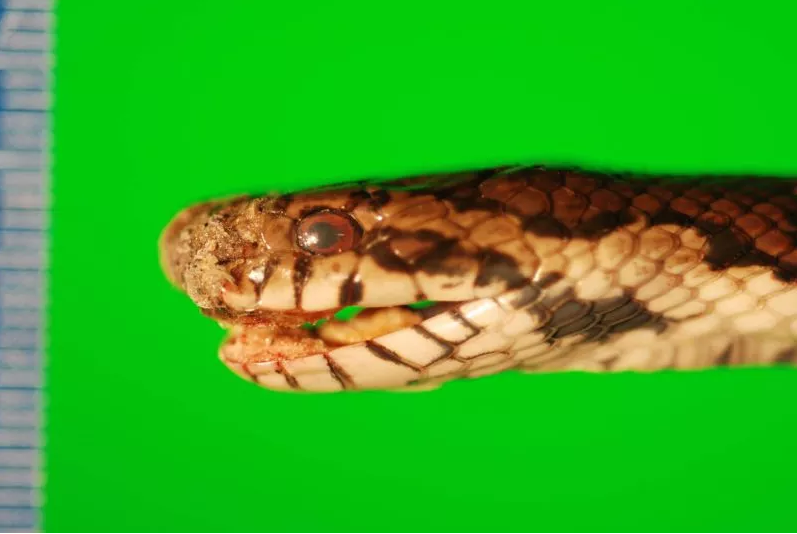

The culprit behind a disease that causes raised blisters, crusted-over eyes and snouts, discolored skin patches, and ultimately death in several snake species has been identified. A fungus called Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola is responsible for the snake deaths in the American Midwest and East, researchers now say.

Researchers had suspected O. ophiodiicola was responsible for snake fungal disease (SFD) because they had found the fungus on snakes that died of SFD in the past. But the new study is the first to confirm a link between the fungus and the disease, the researchers said.

The finding documents how the disease progresses in snakes, and may help researchers create strategies to treat infected snakes and mitigate the fungus near vulnerable snake populations, the researchers said. [See Images of the Snake Fungal Disease]

Wildlife experts first learned about snake fungal disease in 2006, when snakes in New Hampshire began dying after getting serious skin infections. Since then, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has confirmed the disease in at least seven species of snakes in nine states: Illinois, Florida, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Tennessee and Wisconsin.

"The loss of certain snake species in eastern North America could have widespread negative impacts on ecosystems," study lead author Jeffrey Lorch, a USGS National Wildlife Health Center scientist, said in a statement. "Pinpointing the SFD-causing fungus can help conserve snake populations threatened by this disease."

In the study, researchers infected eight healthy snakes with O. ophiodiicola in the laboratory. After four to eight days, the snakes developed swelling, crusty rough patches and lesions on their bodies that were identical to those seen in snakes with snake fungal disease, the researchers said. Moreover, the lesions contained the O. ophiodiicola fungus.

A separate group of seven snakes that were not exposed to the fungus (but received a sham inoculation instead) did not develop skin infections, nor did they have evidence of O. ophiodiicola on their bodies, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Interestingly, the infected snakes responded to the fungus by molting more frequently than the uninfected snakes did, the researchers found. After 15 to 20 days of exposure to the fungus, the infected snakes began shedding an average of every 15 days, while the uninfected snakes shed an average of every 28 days.

What's more, two of the infected snakes showed signs of anorexia, and other infected snakes rested in exposed areas of their cages. Both of these behaviors could increase the snakes' risk for predation or starvation in the wild, the researchers said. In contrast, the uninfected snakes showed normal behavior.

"These behaviors are uncharacteristic of healthy snakes, and demonstrate how SFD can put snakes at risk in the wild," Lorch said.

Warming temperatures from climate change may help the fungus grow, he added. These changing temperatures may also make it harder for infected snakes' abilities to recover, "because snake immunity is highly dependent on environmental conditions," Lorch said.

Though some people fear snakes, these wild animals are vital to ecosystems, the researchers said. Snakes eat pests such as rodents that damage agricultural crops and carry diseases, and also serve as food for other predators, the scientists said.

The findings were published online Nov. 17 in the journal mBio.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.